Wikimedia Commons

The Cock Lane ghost allegedly haunted a lodging in Cock Lane, a short road adjacent to London’s Smithfield market and a few minutes walk from St Paul’s Cathedral. The haunting, which attracted mass public attention in 1762, centred on three people: William Kent, a usurer from Norfolk, Richard Parsons, a parish clerk, and Parsons’ daughter Elizabeth.

Following the death during childbirth of Kent’s wife, Elizabeth Lynes, he became romantically involved with her sister, Fanny. Canon law prevented the couple from marrying, but they nevertheless moved to London and lodged at the property in Cock Lane, then owned by Parsons. Several accounts of strange knocking sounds and ghostly apparitions were reported, although for the most part they stopped after the couple moved out, but following Fanny’s death from smallpox and Kent’s successful legal action against Parsons over an outstanding debt, they resumed. Parsons claimed that Fanny’s ghost haunted his property and later his daughter. Regular séances were held to determine “Scratching Fanny’s” motives; Cock Lane was often made impassable by the throngs of interested bystanders.

The ghost appeared to claim that Fanny had been poisoned with arsenic and Kent was publicly suspected of being her murderer. But a commission whose members included Samuel Johnson18th-century English writer, critic, editor and lexicographer whose Dictionary of the English Language had far-reaching effects on the development of Modern English. concluded that the supposed haunting was a fraud. Further investigations proved the scam was perpetrated by Elizabeth Parsons, under duress from her father. Those responsible were prosecuted and found guilty; Richard Parsons was pilloried and sentenced to two years in prison.

The Cock Lane ghost became a focus of controversy between the Methodist and Anglican churches, and is referenced frequently in contemporary literature. Charles Dickens is one of several Victorian authors whose work alluded to the story, and the pictorial satirist William Hogarth portrayed the ghost in two of his prints.

Background

In about 1756–57 William Kent, a usurer from Norfolk,[1] married Elizabeth Lynes, the daughter of a grocer from Lyneham. They moved to Stoke Ferry, where Kent kept an inn, and later the local post office. They were apparently very much in love, but their marriage was short-lived as within a month of the move Elizabeth died during childbirth. Her sister Frances – commonly known as Fanny – had during Elizabeth’s pregnancy moved in with the couple and she stayed to care for the infant and its father. The boy did not survive long and rather than leave, Fanny stayed on to take care of William and the house. The two soon began a relationship, but canon law appeared to rule out marriage; when Kent travelled to London to seek advice he was told that as Elizabeth had borne him a living son, a union with Fanny was impossible. In January 1759 therefore, he gave up the post office, left Fanny and moved to London, intending to “purchase a place in some public office” in the hope that “business would erase that passion he had unfortunately indulged”. Fanny meanwhile stayed with one of her brothers at Lyneham.[2]

Despite her family’s disapproval of their relationship, Fanny began to write passionate letters to Kent, “filled with repeated entreaties to spend the rest of their lives together”. He eventually allowed her to join him at lodgings in East Greenwich near London. The two decided to live together as man and wife, making wills in each other’s favour and hoping to remain discreet. In this, however, they did not reckon on Fanny’s relations. The couple moved to lodgings near the Mansion House, but their landlord there may have learnt of their relationship from Fanny’s family, expressing his contempt by refusing to repay a sum of money Kent loaned him (about £20).[a]Based on the RPI, about £27,400 as of 2010.[3] In response, Kent had him arrested.[4]

While attending early morning prayers at the church of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate, William Kent and Fanny met Richard Parsons, the officiating clerk.[4] Although he was generally considered respectable, Parsons was known locally as a drunk and was struggling to provide for his family. He listened to the couple’s plight and was sympathetic, offering them the use of lodgings in his home on Cock Lane, to the north of St Sepulchre’s. Located along a narrow, winding thoroughfare similar to most of central London’s streets, the three-storey house was in a respectable but declining area, and comprised a single room on each floor, connected by a winding staircase.[5] Shortly after Mr and Mrs Kent (as they called themselves) moved in, Kent loaned Parsons 12 guineas, to be repaid at a rate of a guinea per month.[6]

It was while Kent was away at a wedding in the country that the first reports of strange noises began. Parsons had a wife and two daughters; the elder, Elizabeth, was described as a “little artful girl about eleven years of age”.[7] Kent asked Elizabeth to stay with Fanny, who was then several months into a pregnancy, and to share her bed while he was away. The two reported hearing scratching and rapping noises. These were attributed by Mrs Parsons to a neighbouring cobbler, although when the noises recurred on a Sunday, Fanny asked if the cobbler was working that day; Mrs Parsons told her he was not. James Franzen, landlord of the nearby Wheat Sheaf public house, was another witness. After visiting the house he reported seeing a ghostly white figure ascend the stairs. Terrified, he returned home, where Parsons later visited him and claimed also to have seen a ghost.[8][9]

As Fanny was only weeks away from giving birth Kent made arrangements to move to a property at Bartlet’s Court in Clerkenwell, but by January 1760 it was not ready and so they moved instead to an “inconvenient” apartment nearby, intending only a temporary stay.[10][11] However, on 25 January Fanny fell ill. The attending doctor diagnosed the early stages of an eruptive fever and agreed with Kent that their lodgings were inadequate for someone at so critical a stage of pregnancy. Fanny was therefore moved, by coach, to Bartlet’s Court. The next day her doctor returned and met with her apothecary. Both agreed that Fanny’s symptoms were indicative of smallpox. On hearing this, Fanny sent for an attorney, to ensure the will she had had made was in good order, and that Kent would inherit her estate. An acquaintance of Kent’s, Stephen Aldrich, Rector of St John Clerkenwell, reassured her that she would be forgiven for her sins. She died on 2 February.[12]

As sole executor of Fanny’s will, Kent ordered a coffin, but fearful of being prosecuted should the nature of their relationship become known, asked that it remain nameless. On registering the burial he was, however, forced to give a name, and he gave her his own. Fanny’s family was notified and her sister Ann Lynes, who lived nearby at Pall Mall, attended the funeral at St John’s. When Ann learned of the terms of Fanny’s will, which left her brothers and sisters half a crown each and Kent the rest, she tried but failed to block it in Doctors’ Commons. The bulk of Kent’s inheritance was Fanny’s £150 share of her dead brother Thomas’s estate. This also included some land owned by Thomas, sold by the executor of his estate, John Lynes, and Kent received Fanny’s share of that too (almost £95). Her family resented this. Legal problems with Lynes’s sale meant that each of Thomas’s beneficiaries had to pay £45 in compensation to the purchaser, but Kent refused, claiming that he had already spent the money in settling Fanny’s debts. In response to this, in October 1761 John Lynes began proceedings against Kent in the Court of Chancery.[b]The result of these proceedings is not mentioned. Meanwhile, Kent became a stockbroker and remarried in 1761.[13]

Haunting

Echoing the actions of Kent’s previous landlord, Parsons had not repaid Kent’s loan – of which about three guineas was outstanding – and Kent therefore instructed his solicitor to sue him.[10][11] He managed to recover the debt by January 1762, just as the mysterious noises at Cock Lane began again. Catherine Friend had lodged there shortly after the couple left but moved out when she found the noises, which had returned intermittently and which were becoming more frequent, could not be stopped. They apparently emanated from Elizabeth Parsons, who also suffered fits, and the house was regularly disturbed by unexplained noises, likened at the time to the sound of a cat scratching a chair.[7] Reportedly determined to discover their source, Richard Parsons had a carpenter remove the wainscotting around Elizabeth’s bed.[14] He approached John Moore, assistant preacher at St Sepulchre’s since 1754 and rector of St Bartholomew-the-Great in West Smithfield since June 1761. The presence of one ghost, presumed to belong to Fanny’s sister, Elizabeth, had already been noted while Fanny lay dying, and the two concluded that the spirit now haunting Parsons’ house must be that of Fanny Lynes herself. The notion that a person’s spirit might return from the dead to warn those still alive was a commonly held belief, and the presence of two apparently restless spirits was therefore an obvious sign to both men that each ghost had an important message to disclose.[15]

Parsons and Moore devised a method of communication; one knock for yes, two knocks for no. Using this system, the ghost appeared to claim that Fanny had been murdered. It was conjectured that the mysterious figure in white which so terrified James Franzen, presumed to be the ghost of Elizabeth, had appeared there to warn her sister of her impending death. As the first ghost had seemingly vanished, this charge against Kent – that he murdered Elizabeth – was never acted on, but through repeated questioning of Fanny’s ghost it was divined that she had died not from the effects of smallpox, but rather from arsenic poisoning. The deadly toxin had apparently been administered by Kent about two hours before Fanny died and now, it was supposed, her spirit wanted justice. Moore had heard from Parsons how Kent had pursued the debt he was owed, and he had also heard from Ann Lynes, who had complained that as Fanny’s coffin lid was screwed down she had not been able to see her sister’s corpse. Moore thought that Fanny’s body might not show any visible signs of smallpox and that if she had been poisoned, the lack of scarring would have been something Kent would rather keep hidden. As a clergyman with inclinations toward Methodism he was inclined to trust the ghost, but for added support he enlisted the aid of Thomas Broughton, an early Methodist. Broughton visited Cock Lane on 5 January and left convinced the ghost was real. The story spread through London, The Public Ledger began to publish detailed accounts of the phenomenon, and Kent fell under public suspicion as a murderer.[16][17]

Séances

After reading the veiled accusations made against him in The Public Ledger, Kent determined to clear his name, and accompanied by a witness went to see John Moore. The Methodist showed Kent the list of questions he and Parsons had drawn up for the ghost to answer. One concerned William and Fanny’s marital status, prompting Kent to admit that they never married. Moore told him he did not think he was a murderer, rather, he believed the spirit’s presence indicated that “there was something behind darker than all the rest, and that if he would go to Parson’s house, he might be a witness to the same and convinced of its reality”. On 12 January therefore, Kent enlisted the aid of the two physicians who attended Fanny in her last days, and with Broughton, went to Cock Lane. On the house’s upper floor Elizabeth Parsons was publicly undressed, and with her younger sister was put to bed. The audience sat around the bed, positioned in the centre of the room. They were warned that the ghost was sensitive to disbelief and told that they should accord it due respect. When the séance began, a relative of Parsons, Mary Frazer,[7] ran around the room shouting “Fanny, Fanny, why don’t you come? Do come, pray Fanny, come; dear Fanny, come!” When nothing happened, Moore told the group the ghost would not come as they were making too much noise. He asked them to leave the room, telling them he would try to contact the ghost by stamping his foot. About ten minutes later they were told the ghost had returned and that they should re-enter the room.[18] Moore then started to run through his and Parsons’ list of questions:

“Did you die naturally?” –Two knocks

“By poison?” –One knock

“Did any person other than Mr. Kent administer it?” –Two knocks

After more questions, a member of the audience exclaimed “Kent, ask this Ghost if you shall be hanged”. He did so, and the question was answered by a single knock. Kent exclaimed “Thou art a lying spirit, thou are not the ghost of my Fanny. She would never have said any such thing.”[18] Public interest in the story grew when it was discovered that the ghost appeared to follow Elizabeth Parsons. She was removed to the house of a Mr Bray, where on 14 January, in the presence of two unidentified nobles, more knocking sounds were heard.[18] A few days later she was returned to Cock Lane, where on 18 January another séance was held. In attendance were Kent, the apothecary, and local parish priest and incumbent of St John Clerkenwell, Stephen Aldrich.[19] On that occasion, when a clergyman used a candle to look under the bed, the ghost “refused” to answer, Frazer claiming “she [the ghost] loving not light”. After a few minutes of silence the questioning continued, but when Moore asked if the ghost would appear in court against Kent, Frazer refused to ask the question.[20]

When they lived at Cock Lane William and Fanny had employed a maid, Esther “Carrots” Carlisle (Carrots on account of her red hair). She had since moved to a new job and knew nothing of the haunting, but seeking evidence of Fanny’s poisoning, Moore went to question her. Carrots told him that Fanny had been unable to speak in the days before she died, so Moore invited her to a séance, held on 19 January. Once there, she was asked to confirm that Fanny had been poisoned, but Carrots remained adamant that Fanny had said nothing to her, telling the party that William and Fanny had been “very loving, and lived very happy together.” Kent arrived later that night, this time with James Franzen and priests William Dodd and Thomas Broughton. Frazer began with her usual introduction before Moore sent her out, apparently irritated by her behaviour. He then asked the party of about twenty to leave the room, calling them back a few minutes later.[21] This time, the séance centred on Carrots, who addressed the ghost directly:

“Are you angry with me, Madam?” –One knock

“Then I am sure, Madam, you may be ashamed of yourself for I never hurt you in my life.”

At this, the séance was ended. Frazer and Franzen remained alone in the room, the latter reportedly too terrified to move. Frazer asked if he would like to pray and was angered when he apparently could not. The séance resumed and Franzen later returned to his home, where he and his wife were reportedly tormented by the ghost’s knocking in their bedchamber.[22]

Investigation

On 20 January another séance was held, this time at the home of a Mr Bruin, on the corner of nearby Hosier Lane. Among those attending was a man “extremely desirous of detecting the fraud, and discovering the truth of this mysterious affair”, who later sent his account of the night to the London Chronicle. He arrived with a small party which included James Penn of St Ann’s in Aldersgate. Inside the house, a member of the group positioned himself against the bed, but was asked by one of the ghost’s sympathisers to move. He refused, and following a brief argument the ghost’s supporters left. The gentleman then asked if Parsons would allow his daughter to be moved to a room at his house, but was refused. For the remainder of the night the ghost made no sound, while Elizabeth Parsons, now extremely agitated, displayed signs of convulsions. When questioned she confirmed that she had seen the ghost, but that she was not frightened by it. At that point several of the party left, but at about 7 am the next morning the knocking once more recommenced. Following the usual questions about the cause of Fanny’s death and who was responsible, the interrogation turned to her body, which lay in the vaults of St John’s.[23]

Parsons agreed to move his daughter to Aldrich’s house for further testing on 22 January, but when that morning Penn and a man of “veracity and fortune” called on Parsons and asked for Elizabeth, the clerk told them she was not there and refused to reveal her whereabouts. Parsons had spoken with friends and was apparently worried that Kent had been busy with his own investigations.[c]Evidence of these investigations exists in a letter which appeared in a newspaper in February 1762, signed by a “J. A. L.”, which gave a detailed report on how Fanny had arrived in London, and which claimed that Kent had drawn up Fanny’s will in his favour. It made no specific accusations, but as its author observed, Kent’s actions had had “the desired effect”. Kent later claimed to know the identity of its author, who, Grant (1965) surmises, was a member of the Lynes family. Grant also writes that the letter was printed to maintain pressure on Kent.[24] Instead, he allowed Elizabeth to be moved that night to St Bartholomew’s Hospital, where another séance was held. Nothing was reported until about 6 am, when three scratches were heard, apparently while the girl was asleep. The approximately twenty-strong audience complained that the affair was a deception. Once Elizabeth woke she began to cry, and once reassured that she was safe admitted that she was afraid for her father, “who must needs be ruined and undone, if their matter should be supposed to be an imposture.” She also admitted that although she had appeared to be asleep, she was in fact fully aware of the conversation going on around her.[25]

| Whereas several advertisements have appeared in the papers reflecting upon my character, who am father of the child which now engrosses the talk of the town; I do hereby declare publicly, that I have always been willing and am now ready to deliver up my child for trial into the hands of any number of candid and reasonable men, requiring only such security for a fair and gentle treatment of my child, as no father of children or man of candour would refuse.[26] — The Public Ledger, 26 January 1762 |

Initially only The Public Ledger reported on the case, but once it became known that noblemen had taken an interest and visited the ghost at Mr Bray’s house on 14 January, the story began to appear in other newspapers. The St. James’s Chronicle and the London Chronicle printed reports from 16–19 January (the latter the more sceptical of the two), and Lloyd’s Evening Post from 18–20 January. The story spread across London and by the middle of January the crowds gathered outside the property were such that Cock Lane was rendered impassable. Parsons charged visitors an entrance fee to “talk” with the ghost, which, it was reported, did not disappoint.[17][27][28] After receiving several requests to intercede, Samuel Fludyer, Lord Mayor of London, was on 23 January approached by Alderman Gosling, John Moore and Parsons. They told him of their experiences but Fludyer was reminded of the then recent case of fraudster Elizabeth Canning and refused to have Kent or Parsons arrested (on charges of murder and conspiracy respectively). Instead, against a backdrop of hysteria caused in part by the newspapers’ relentless reporting of the case, he ordered that Elizabeth be tested at Aldrich’s house. Meanwhile, Elizabeth was again the subject of study, in two séances held 23–24 January.[29] Parsons accepted the Lord Mayor’s decision, but asked that “some persons connected with the girl might be permitted to be there, to divert her in the day-time”. This was refused, as were two similar requests, Aldrich and Penn insisting that they would accept only “any person or persons, of strict character and reputation, who are housekeepers”. Aldrich and Penn’s account of their negotiations with Parsons clearly perturbed the clerk, as he defended his actions in the Public Ledger. This prompted Aldrich and Penn to issue a pointed retort in Lloyd’s Evening Post: “We are greatly puzzled to find Mr. Parsons asserting that he hath been always willing to deliver up the child, when he refused a gentleman on Wednesday evening the 20th inst. … What is to be understood, by requiring security”?[26]

Elizabeth was taken to the house of Jane Armstrong on 26 January, where she slept in a hammock. The continued noises strengthened the resolve of the ghost’s supporters, while the press’s ceaseless reporting of the case continued. Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford, announced that with the Duke of York, Lady Northumberland, Lady Mary Coke and Lord Hertford, he was to visit Cock Lane on 30 January. After struggling through the throngs of interested visitors though, he was ultimately disappointed; the Public Advertiser observed that “the noise is now generally deferred till seven in the morning, it being necessary to vary the time, that the imposition may be the better carried on”.[30]

Exposure

With Lord Dartmouth Aldrich began to draw together the people who would be involved in his investigation. They chose the matron of a local lying-in hospital as principal lady-in-waiting, the critic and controversialist Bishop John Douglas, and Dr George Macaulay. A Captain Wilkinson was also included on the committee; he had attended one séance armed with a pistol and stick; the former to shoot the source of the knocking, and the latter to make his escape (the ghost had remained silent on that occasion). James Penn and John Moore were also on the committee, but its most prominent member was Dr Samuel Johnson.[31]

Disappointed that the ghost failed to reveal itself, Moore now told Kent he believed it was an imposter, and that he would help expose it. Kent asked him to admit the truth and write an affidavit of what he knew, so as to end the affair and restore Kent’s reputation, but Moore refused, telling him that he still believed that the spirit’s presence was a reminder of his sin.[32][d]Kent did, however, manage to issue an affidavit, signed by Fanny’s doctor and her apothecary on 8 February.[33] Moore’s view of the couple’s relationship was shared by many, including Mrs Parsons, who believed that the supposed ghost of Elizabeth Kent had disapproved of her sister’s new relationship.[34]

Wikimedia Commons

Another séance on 3 February saw the knocking continue unabated, but by then Parsons was in an extremely difficult – and serious – situation. Keen to prove the ghost was not an imposture he allowed his daughter to be examined at a house on The Strand from 7–10 February, and at another house in Covent Garden from 14 February. There she was tested in a variety of ways which included being swung up in a hammock, her hands and feet extended. As expected, the noises commenced, but stopped once Elizabeth was made to place her hands outside the bed. For two nights the ghost was silent. Elizabeth was told that if no more noises were heard by Sunday 21 February, she and her father would be committed to Newgate Prison. Her maids then saw her conceal on her person a small piece of wood about 6 by 4 inches (150 by 100 mm) and informed the investigators. More scratches were heard but the observers concluded that Elizabeth was responsible for the noises, and that she had been forced by her father to make them. Elizabeth was allowed home shortly after.[35][36]

On or about 25 February, a pamphlet sympathetic to Kent’s case was published, called The Mystery Revealed, and most likely written by Oliver Goldsmith.[37] Meanwhile, Kent was still trying to clear his name, and on 25 February he went to the vault of St John’s, accompanied by Aldrich, the undertaker, the clerk and the parish sexton. The group was there to prove beyond any doubt that a recent newspaper report, which claimed that the supposed removal of Fanny’s body from the vault accounted for the ghost’s failure to knock on her coffin, was false. The undertaker removed the lid to expose Fanny’s corpse, “and a very awful shocking sight it was”.[38] For Moore this was too much, but the retraction he published was not enough to keep him from being charged by the authorities with conspiracy, along with Richard Parsons and his wife, Mary Frazer, and Richard James, a tradesman.[39]

Trial

The trial of all five was held at the Guild Hall in London on 10 July 1762. Presiding over the case was Lord Chief Justice William Murray. Proceedings began at 10 am, “brought by William Kent against the above defendants for a conspiracy to take away his life by charging him with the murder of Frances Lynes by giving her poison whereof she died”. The courtroom was crowded with spectators, who watched as Kent gave evidence against those in the dock. He told the court about his relationship with Fanny and of her resurrection as “Scratching Fanny” (so-called because of the scratching noises made by the “ghost”).[7] James Franzen was next on the stand, his story corroborated by Fanny’s servant, Esther “Carrots” Carlisle, who testified later that day. Dr Cooper, who had served Fanny as she lay dying, told the court that he had always believed the strange noises in Cock Lane to be a trick, and his account of Fanny’s illness was supported by her apothecary, James Jones. Several other prosecution witnesses described how the hoax had been revealed, and Richard James was accused by the prosecution’s last witness of being responsible for some of the more offensive material published in the The Public Ledger.[40]

The defence’s witnesses included some of those who had cared for Elizabeth Parsons and who presumably still believed that the ghost was real. Other witnesses included the carpenter responsible for removing the wainscotting from Parsons’ apartment and Catherine Friend, who to escape the knocking noises had left the property. One witness’s testimony caused the court to burst into laughter, at which she replied “I assure you gentlemen, it is no laughing matter, whatever you may think of it.” Thomas Broughton was also called, as was a priest surnamed Ross, one of those who had questioned the ghost. Judge Murray asked him “Whether he thought he had puzzled the Ghost, or the Ghost had puzzled him?” John Moore was offered support by several esteemed gentlemen and presented Murray with a letter from Thomas Secker, Archbishop of Canterbury, who sought to intercede on his behalf. Murray placed the letter in his pocket, unopened, and told the court “it was impossible it could relate to the cause in question.” Richard James and Richard Parsons also received support from various witnesses, some of whom although acknowledging Parsons’ drink problem, told the court they could not believe he was guilty.[40]

The trial ended at about 9:30 pm. The judge spent about 90 minutes summing up the case, but it took the jury only 15 minutes to reach a verdict of guilty for all five defendants. The following Monday, two others responsible for defaming Kent were found guilty and later fined £50 each. The conspirators were brought back on 22 November but sentencing was delayed in the hope that they could agree on the level of damages payable to Kent. Having failed to do so they returned on 27 January 1763 and were committed to the King’s Bench Prison until 11 February, by which time John Moore and Richard James had agreed to pay Kent £588; they were subsequently admonished by Justice Wilmot and released. The following day, the rest were sentenced:[41]

— Annual Register, vol cxlii. and Gentleman’s MagazineMonthly compendium of the best news, essays and information from the daily and weekly newspapers, published from 1731 until 1914., 1762, p. 43 and p. 339

Parsons, all the while protesting his innocence, was also sentenced to two years imprisonment. He stood in the pillory on 16 March, 30 March and finally on 8 April. In contrast to other criminals the crowd treated him kindly, making collections of money for him.[41]

Legacy

Wikimedia Commons

The Cock Lane ghost was a focus for a contemporary religious controversy between the Methodists and orthodox Anglicans. Belief in a spiritual afterlife is a requirement for most religions, and in every instance where a spirit had supposedly manifested itself in the real world, the event was cherished as an affirmation of such beliefs.[44] In his youth, John Wesley had been strongly influenced by a supposed haunting at his family home of Epworth RectorySite of supposed paranormal events that occurred in 1716. , and that experience was carried through to the religion he founded, which was regularly criticised for its position on witchcraft and magic. Methodism, although far from a united religion, became almost synonymous with a belief in the supernatural.[45] Some of its followers therefore gave more credence to the reality of the Cock Lane ghost than did the Anglican establishment, which considered such things to be relics of the country’s Catholic past. This was a view that was epitomised in the conflict between the Methodist John Moore and the Anglican Stephen Aldrich.[46] In his 1845 memoirs, Horace Walpole, who had attended one of the séances, accused the Methodists of actively working to establish the existence of ghosts. He described the constant presence of Methodist clergymen near Elizabeth Parsons and implied that the church would recompense her father for his troubles.[47]

Samuel Johnson was committed to his Christian faith and shared the views of author Joseph Glanvill, who, in his 1681 work Saducismus Triumphatus, wrote of his concern over the advances made against religion and a belief in witchcraft, by atheism and scepticism. For Johnson the idea that an afterlife might not exist was an appalling thought, but although he thought that spirits could protect and counsel those still living, he kept himself distant from the more credulous Methodists, and recognised that his religion required proof of an afterlife.[48]

Johnson’s role in revealing the nature of the hoax was insufficient to keep the satirist Charles Churchill from mocking his apparent credulity in his 1762 work The Ghost.[49] He resented Johnson’s lack of enthusiasm for his writing and with the character of Pomposo, written as one of the more credulous of the ghost’s investigators, used the satire to highlight a “superstitious streak” in his subject. Johnson paid this scant attention, but was said to have been more upset when Churchill again mocked him for his delay in releasing Shakespeare.[50] Publishers were at first wary of attacking those involved in the supposed haunting, but Churchill’s satire was one of a number of publications which, following the exposure of Parsons’ deception, heaped scorn on the affair. The newspapers searched for evidence of past impostures and referenced older publications such as Reginald Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584).[51] The ghost was referenced in an anonymous work entitled Anti-Canidia: or, Superstition Detected and Exposed (1762), which sought to ridicule the credulity of those involved in the Cock Lane case. The author described his work as a “sally of indignation at the contemptible wonder in Cock-lane”.[52] Works such as The Orators (1762) by Samuel Foote, were soon available.[53][54] Farcical poems such as Cock-lane Humbug were released, theatres staged plays such as The Drummer and The Haunted House.[55]

Wikimedia Commons

Oliver Goldsmith, who had in February 1762 published The Mystery Revealed, may also have been responsible for the satirical illustration English Credulity or the Invisible Ghost (1762). It shows a séance as envisioned by the artist, with the ghost hovering above the heads of the two children in the bed. To the right of the bed a woman deep in prayer exclaims “O! that they would lay it in the Red Sea!” Another cries “I shall never have any rest again”. The English magistrate and social reformer John Fielding, who was blind, is pictured entering from the left saying “I should be glad to see this spirit”, while his companion says “Your W——r’s had better get your Warrant back’d by his L—rds—p”, referring to a Middlesex magistrate’s warrant which required an endorsement from the Lord Mayor, Samuel Fludyer. A man in tall boots, whip in hand, says: “Ay Tom I’ll lay 6 to 1 it runs more nights than the Coronation”[e]The Coronation was a theatrical play based on the coronation of George III.[57] and his companion remarks “How they swallow the hum”. A clergymen says “I saw the light on the Clock” while another asks “Now thou Infidel does thou not believe?”, prompting his neighbour to reply “Yes if it had happen’d sooner ‘t would have serv’d me for a new Character in the Lyar the Story would tell better than the Cat & Kittens”.[f]The Lyar was a comedy in three acts produced by the dramatist Samuel Foote.[57] Another clergyman exclaims “If a Gold Watch knock 3 times”, and a Parson asks him “Brother don’t disturb it”. On the wall, an image of The Bottle Conjuror is alongside one of Elizabeth Canning, whose fraud had so worried Samuel Fludyer that he had refused to arrest either Parsons or Kent.[58]

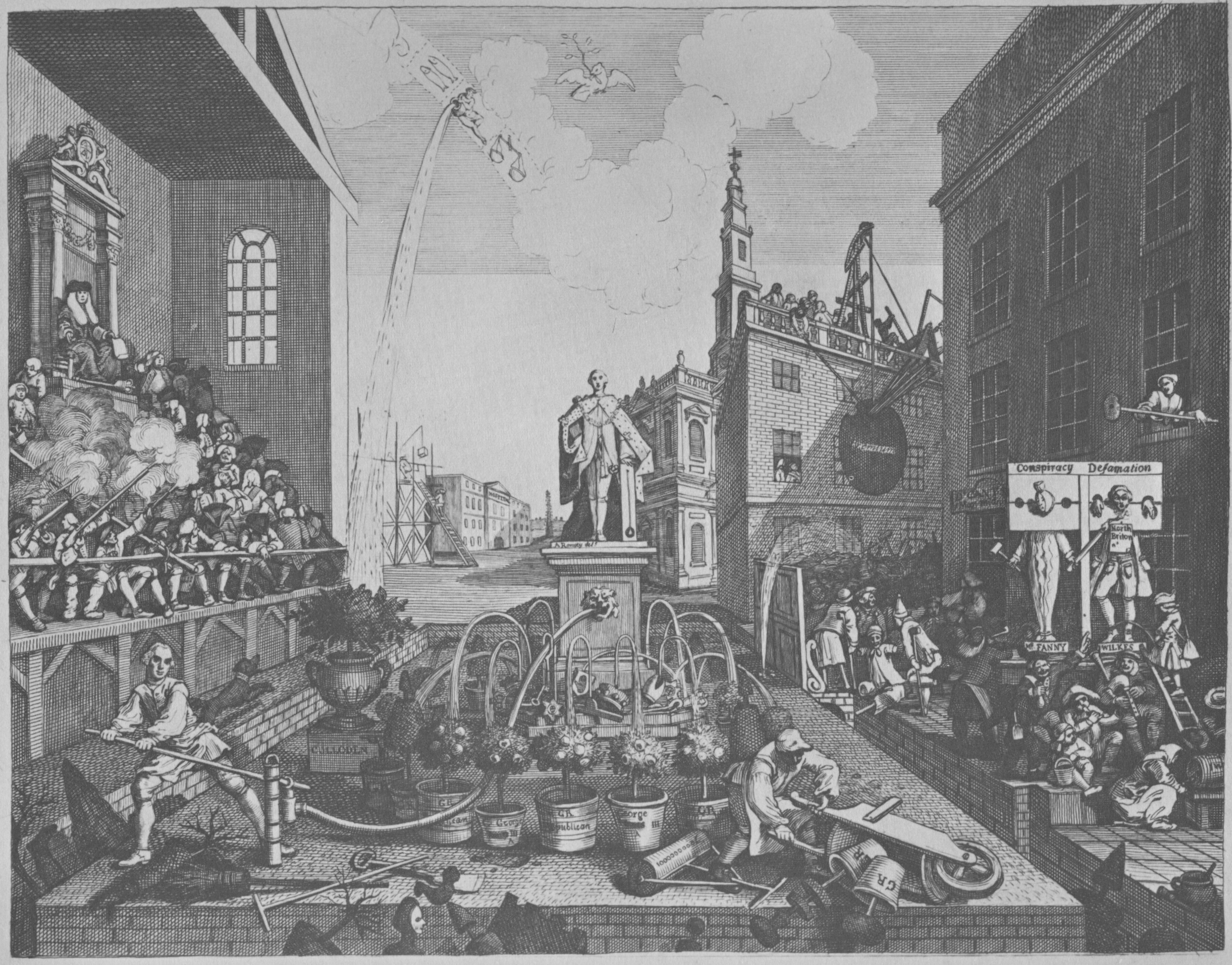

Playwright David Garrick dedicated the enormously successful The Farmer’s Return to the satirical artist William Hogarth. The story concerns a farmer who regales his family with an account of his talk with Miss Fanny, the comedy being derived from the reversal of traditional roles: the sceptical farmer poking fun at the credulous city-folk.[55][59] Hogarth made his own observations of the Cock Lane ghost, with obvious references in Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism (1762). This illustration makes a point of attacking Methodist ministers, one of whom is seen to slip a phallic “ghost” into a young woman’s bodice.[43] He again attacked the Methodists in The Times, Plate 2 (1762–1763), placing an image of Thomas Secker (who had tried to intervene on behalf of the Methodists) behind the Cock Lane ghost, and putting the ghost in the same pillory as the radical politician John Wilkes, which implied a connection between the demagoguery surrounding the Methodists and Pittites.[60][61] The print enraged Bishop William Warburton, who although a vocal critic of Methodism, wrote:

The 19th-century author Charles Dickens – whose childhood nursemaid Mary Weller may have affected him with a fascination for ghosts – made reference to the Cock Lane ghost in several of his books.[62][g]Slater (1983) theorises that Weller may not have provided Dickens with the ghostly stories that affected his childhood.[63] One of Nicholas Nickleby’s main characters and a source of much of the novel’s comic relief, Mrs. Nickleby, claims that her great-grandfather “went to school with the Cock-lane Ghost” and that “I know the master of his school was a Dissenter, and that would in a great measure account for the Cock-lane Ghost’s behaving in such an improper manner to the clergyman when he grew up.”[64] Dickens also very briefly mentions the Cock Lane ghost in A Tale of Two Cities[65] and Dombey and Son.[66]

According to a 1965 source, the site of Parson’s lodgings corresponded to the building with the modern address 20 Cock Lane.[5] The house was believed to have been built in the late 17th century, and was demolished in 1979.[67]

Notes

| a | Based on the RPI, about £27,400 as of 2010.[3] |

|---|---|

| b | The result of these proceedings is not mentioned. |

| c | Evidence of these investigations exists in a letter which appeared in a newspaper in February 1762, signed by a “J. A. L.”, which gave a detailed report on how Fanny had arrived in London, and which claimed that Kent had drawn up Fanny’s will in his favour. It made no specific accusations, but as its author observed, Kent’s actions had had “the desired effect”. Kent later claimed to know the identity of its author, who, Grant (1965) surmises, was a member of the Lynes family. Grant also writes that the letter was printed to maintain pressure on Kent.[24] |

| d | Kent did, however, manage to issue an affidavit, signed by Fanny’s doctor and her apothecary on 8 February.[33] |

| e | The Coronation was a theatrical play based on the coronation of George III.[57] |

| f | The Lyar was a comedy in three acts produced by the dramatist Samuel Foote.[57] |

| g | Slater (1983) theorises that Weller may not have provided Dickens with the ghostly stories that affected his childhood.[63] |

References

- p. 171

- pp. 6–7

- pp. 4–10

- pp. 4–6

- p. 10

- pp. 39–40

- pp. 14–15

- p. 28

- pp. 12–13

- pp. 13–16

- pp. 16–19

- p. 165

- pp. 20–21

- pp. 23–25

- p. 172

- pp. 26–29

- pp. 80–87

- pp. 30–32

- pp. 32–34

- pp. 34–36

- pp. 38–41

- p. 43

- pp. 41–44

- p. 54

- p. 232

- pp. 463–464

- pp. 44–45, 51–52

- pp. 55–56

- pp. 56–57

- p. 73

- p. 77

- pp. 39–42

- pp. 73–76

- p. 169

- p. 364

- pp. 76–77

- p. 80

- pp. 110–112

- pp. 113–114

- p. 148

- pp. 143–144

- p. 60

- pp. 12–14

- pp. 47–54, 87

- pp. 146–147

- pp. 60–63

- pp. 352–353

- pp. 81–82

- pp. 81–101

- p. 173

- pp. 14–16

- p. 300

- p. 46

- pp. 45–46

- p. 366

- pp. 392–393

- p. 150

- p. 218

- p. 383

- p. 655

- p. 1

- p. 64

- p. 105