“You Are Old, Father William” is a poem by Lewis Carroll that appears in his 1865 book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Like most of the poems in Alice, it is a parody of another well-known to children of the time, in this case Robert SoutheyRobert Southey (12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic school, one of the Lake Poets along with William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and England's poet laureate for 30 years from 1813 until his death in 1843 ‘s “The Old Man’s Comforts and How He Gained Them”, originally published in 1799 and now almost forgotten.[1] Carroll’s version “undermines the pious didacticism of Southey’s original and gives Father William an eccentric vitality that rebounds upon his idiot questioner”.[2] The mathematician and popular science writer Martin Gardner calls the poem “one of the undisputed masterpieces of nonsense verse”.[3]

Context

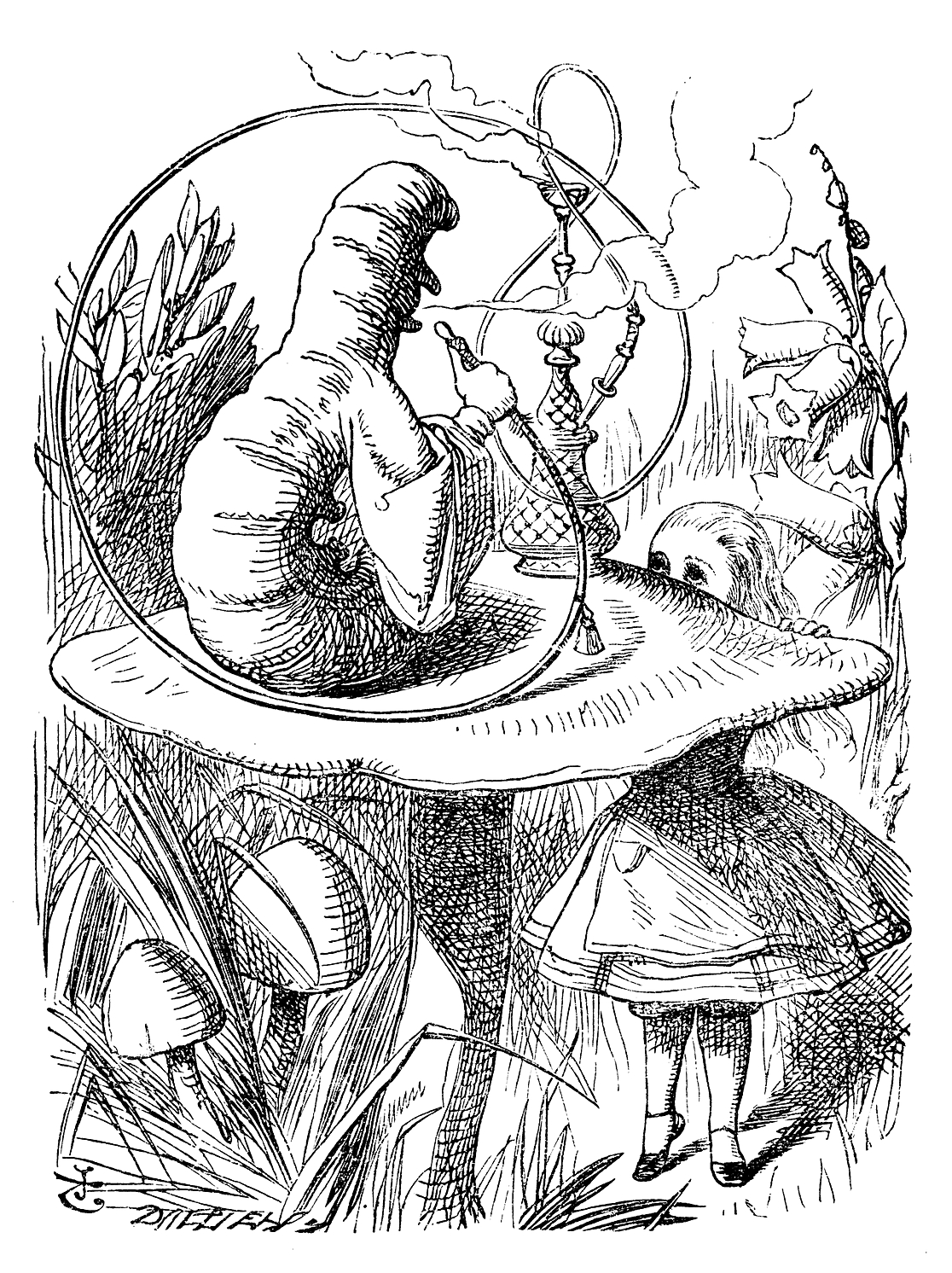

Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland tells the story of a young girl who, one summer afternoon, follows a white rabbit down a rabbit hole and enters a world in which she meets many strange characters. One is a large blue caterpillar, sitting on top of a mushroom and smoking a hookah.

Alice tells the Caterpillar that she is finding Wonderland to be very confusing; she seems to be changing size every ten minutes, and is having trouble remembering things. She adds that she had tried to repeat “How Doth the Little Busy Bee” earlier, “but it all came out different”. The Caterpillar then asks Alice to recite “You Are Old, Father William”, which she attempts to do. When Alice has finished, she admits that “some of the words have got altered”, but the Caterpillar observes that her recitation is “wrong from beginning to end”.[4]

Alice’s version

“You are old, Father William,” the young man said,

“And your hair has become very white;

And yet you incessantly stand on your head—

Do you think, at your age, it is right?”

“In my youth,” Father William replied to his son,

“I feared it might injure the brain;

But now that I’m perfectly sure I have none,

Why, I do it again and again.”

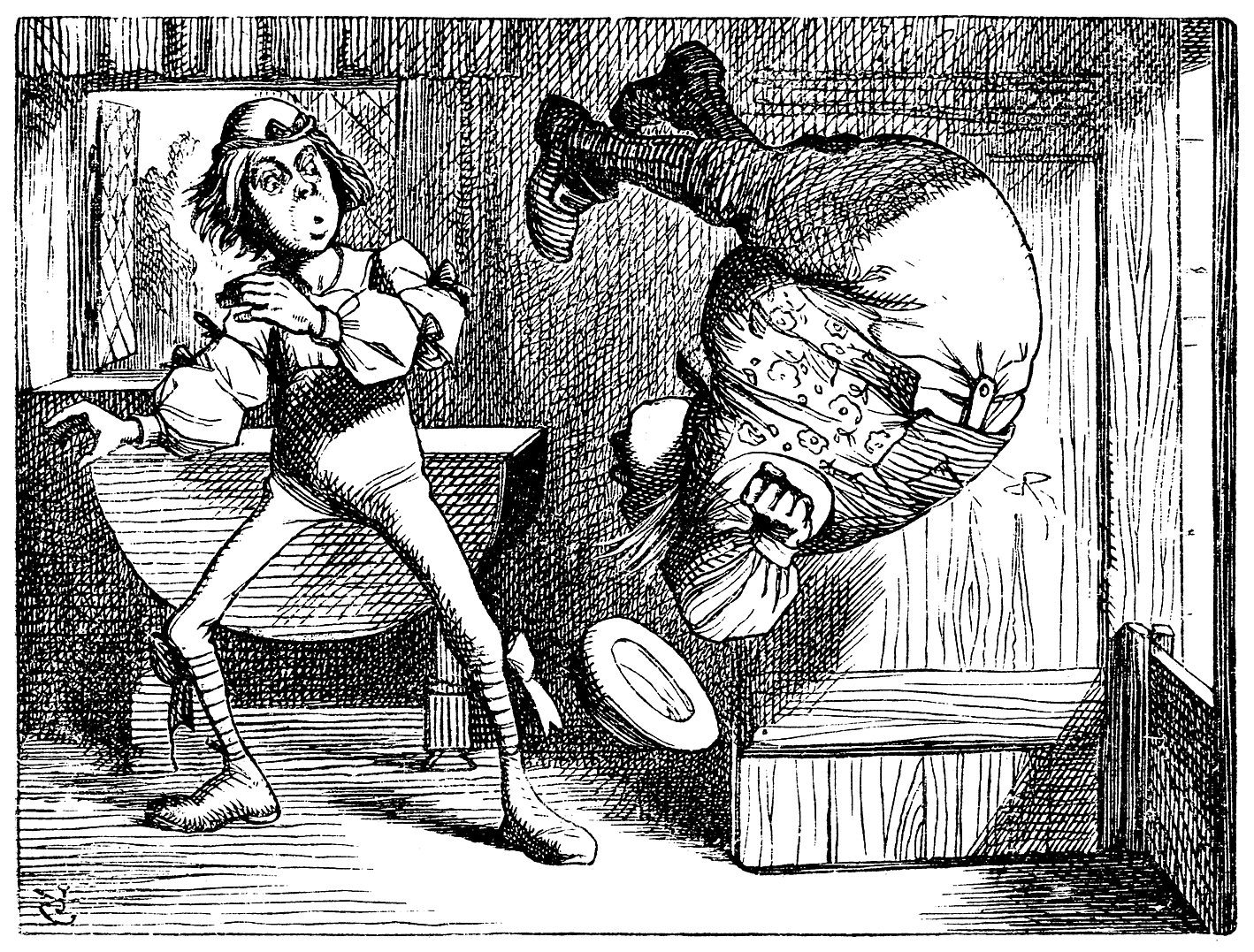

“You are old,” said the youth, “as I mentioned before,

And have grown most uncommonly fat;

Yet you turned a back-somersault in at the door—

Pray, what is the reason of that?”

“In my youth,” said the sage, as he shook his grey locks,

“I kept all my limbs very supple

By the use of this ointment—one shilling the box—

Allow me to sell you a couple.”

“You are old,” said the youth, “and your jaws are too weak

For anything tougher than suet;

Yet you finished the goose, with the bones and the beak—

Pray, how did you manage to do it?”

“In my youth,” said his father, “I took to the law,

And argued each case with my wife;

And the muscular strength, which it gave to my jaw,

Has lasted the rest of my life.”

“You are old,” said the youth, “one would hardly suppose

That your eye was as steady as ever;

Yet you balanced an eel on the end of your nose—

What made you so awfully clever?”

“I have answered three questions, and that is enough,”

Said his father; “don’t give yourself airs!

Do you think I can listen all day to such stuff?

Be off, or I’ll kick you down stairs!”[5]