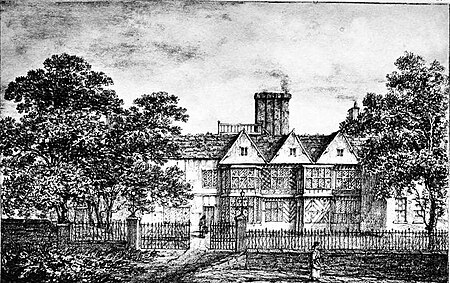

Ancoats Hall was a post-medieval country house built in 1609 in Ancoats, Manchester by Oswald Mosley, a member of the family who were Lords of the Manor of Manchester. The old timber-framed hall, built in the early 17th century, was described by John Aiken in his 1795 book Description of the country from 30 to 40 miles around Manchester. The old hall was demolished in the 1820s and replaced by a brick building in the early neo-Gothic style. The new hall, at the eastern end of Great Ancoats Street between Every Street and Palmerston Street, was demolished in the 1960s.

Old hall

Oswald Mosley, a nephew of Sir Nicholas Mosley, bought the land on which the hall was built in 1609 from the Byrons of Clayton Hall. The house was sequestered by Parliament after Oswald’s son Nicholas Mosley supported the king in the Civil War, but was returned to him after paying a £120 fine. The house remained in the family until Sir John Mosley inherited it from a cousin in 1779, and preferring to live on his estate in Staffordshire, sold it.[1] For a period the embalmed body of Hannah Beswick (known as the Manchester MummyMummified body of Hannah Beswick (1688–1758, a wealthy woman with a pathological fear of premature burial.) was kept at the hall.[2]

In his book, Lancashire Gleanings (1883), William Axon tells of the “curious Manchester tradition”, that in 1744, the Young Pretender, Charles Edward Stuart, visited the town, in disguise, and stayed with Sir Oswald Mosley at Ancoats Hall for several weeks, to assess whether the people of Manchester were “attached to the interests of his family”. The following year, when the Jacobite army rode into Manchester, a young girl was said to have recognised the prince as the “handsome young man of genteel deportment” who had stayed at the hall and who came to the Swan Inn, where she lived, to read the London newspapers three times a week. As the prince passed by the inn with his army in 1745 she exclaimed, “Father, father, that is the gentleman who gave me the half-crown” but her father drove her back into the house with severe threats if she ever mentioned that circumstance again. Axon was not fully convinced by the story as he could find no other evidence for it other than an account in the Sir Oswald Mosley’s Family Memoirs, printed for private circulation.[3]

According to Aiken in 1795, the old hall stood facing north-west on Ancoats Lane (which became a continuation of Great Ancoats Street). Its terraced back gardens sloped towards the River Medlock. The two-storey hall had attics and a hipped roof. It was constructed in timber and plaster. Its front had three gables and a square tower and the back and its west wing had been rebuilt. Britton, in 1807 described its upper storeys as overhanging the ground floor, and windows projecting from the face of the building.[1]

New hall

During the Industrial Revolution at the end of the 18th century Ancoats Hall was bought by one of the new elite – a wealthy Manchester merchant, William Rawlinson.[4] By 1827 it was owned by George Murray (of nearby Murrays’ Mills[5]). Murray demolished the old hall and replaced it with a brick hall in the fashionable neo-Gothic style.[1]After his death, his wife Jane remained there with her son James for at least ten years until James moved to London, and by 1868 Jane Murray had moved to the home of her son, Benjamin, in the Polygon in Ardwick.[6]

The hall and its surrounding lands were bought and used by the Midland Railway for Ancoats railway station that opened in 1870.[7] From 1886 the hall was used for Manchester Art Museum, founded by Thomas Coglan Horsfall as a philanthropic project. The Manchester University Settlement, an unofficial hall of residence, was established in part of the premises in 1895 and merged with the museum six years later.[8] By this time the hall stood in squalid urban surroundings and its gardens had been built over.[1] The new hall was in turn demolished in the 1960s after falling into disrepair.