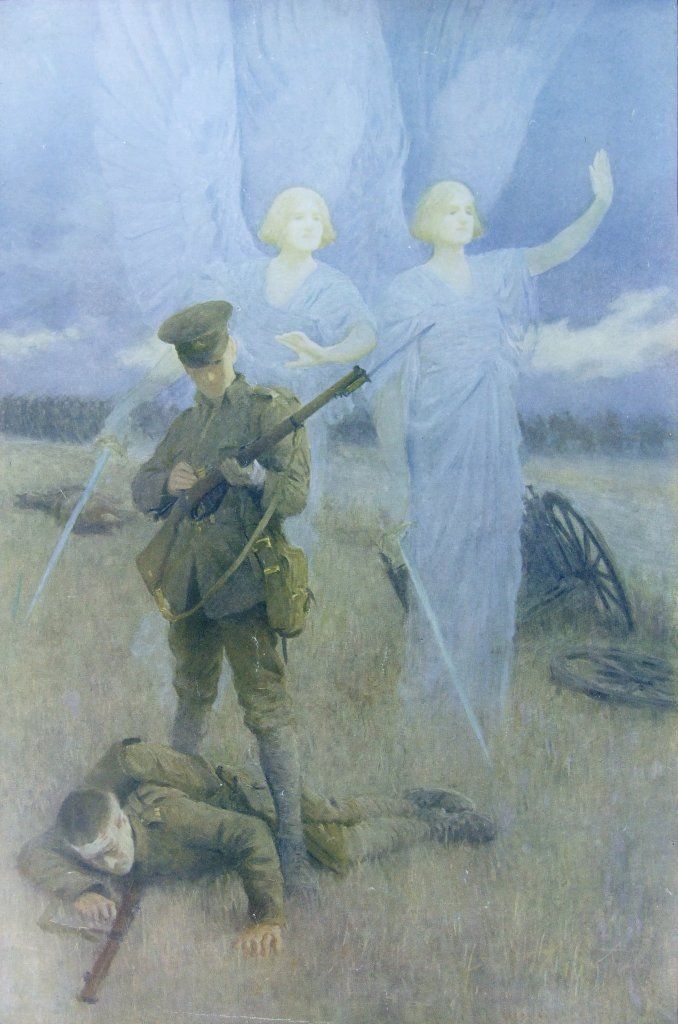

The Angels of Mons are supernatural beings widely reported as having defended the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) against overwhelming odds in the first major engagement of the Great War, the Battle of Mons, on Sunday 23 August 1914. The story has become the “most widely believed and influential legend to emerge from the First World War”, although several different versions exist, including one of a ghostly company of English archers.[1] The cultural historian Susan Owens has speculated that ghosts became more necessary than ever during the horror of the Great War,[2] but accounts of spectral armies or divine intervention are encountered throughout recorded history. In the Greek myths, for instance, the gods often intervene on the side of their favoured warriors.[3]

Background

The British had been hurriedly deployed to support the French along a 20-mile (32 km) line west of the Belgian town of Mons in an attempt to halt the advance of the German Army into France. The battle began at 9:00 am, when the artillery of General von Kluck’s First Army opened fire on the British positions. Unknown to the BEF however, the French had retreated, leaving the British Army outnumbered almost three to one and vulnerable to encirclement.[4]

Despite their best efforts, and in danger of being wiped out, the British were forced to retreat to a line about two miles (3 km) to the south of Mons. It is estimated that the battle claimed the lives of between five and ten thousand Germans and 1600 British. That number of British casualties rose to fifteen thousand during the subsequent Great Retirement, which saw the BEF forced to withdraw a further 200 miles (322 km) over the following thirteen days.[4][a]Fifteen thousand men represents fifteen per cent of the BEF’s total force, lost in one engagement.

Earliest accounts

The first account of any supernatural intervention in this initial encounter between the British and German armies during the First World War occurs in a private letter written by John Charteris, the aide-de-camp to Lieutenant-General Sir Douglas Haig, dated 5 September 1914:

Another account identified the ghostly horseman as St George, who led the troops against the German onslaught.[b]St George had been the patron saint and protector of English armies since the 11th-century First Crusade.[6] All the accounts seemed to agree on one thing however, that at a critical moment in the battle the British soldiers saw a bright light or cloud in the sky, following which some supernatural agency came to their aid.[1]

“The Bowmen”

The writer Arthur Machen read an account of the Battle of Mons in the Sunday newspapers a week after its conclusion. It inspired him to write “The Bowmen”, a short story that was printed in the Evening News on 29 September 1914. In it he describes a soldier who invokes the aid of St George at a critical point in the battle, and is astonished when the saint appears on the battlefield accompanied by a ghostly company of archers who had fought at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. With a cry of “St George for Merry England” the archers unleash a deadly assault on the German lines.[7]

Many of Machen’s readers believed that he was reporting in the newspaper what had actually been observed, even though he always said that his story had “no foundation in fact of any sort”.[7]

Historical research

David Clarke, a lecturer in journalism at Sheffield Hallam University and researcher into folklore, writes in his book The Angel of Mons (2004) that the story is “a classic example of a rumour that was widely believed despite its many internal inconsistencies”.[8] The only evidence of any kind of supernatural intervention in the Battle of Mons before the publication of Machen’s story is the letter written by Charteris, who later became the British Army’s Chief Intelligence Officer.[9] The historian Lyn Macdonald is on record as having stated that:[10]

The military historians Alan S. Coulson and Michael E. Hanlon are of the same view:[11]

Modern interpretation

Carl Jung, the founder of analytical psychology, accepted stories of the Angel of Mons at face value in his 1958 book Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies, and characterised them as a variation on what he called visionary rumours.[12] He hypothesised that whatever the soldiers at Mons may have seen was some kind of projection manifesting the unconscious background of war.[13]

From a sociological perspective, legends such as the Angel of Mons can be categorised as FOAF-tales, in which the source is described as a “friend of a friend”; the themes of such tales reflect the fears and moral judgements of their time.[14]

It may be however, that the legend of the Angel of Mons is best thought of simply as the first urban myth, as suggested in a 2002 Radio 4 documentary.[15]

Notes

| a | Fifteen thousand men represents fifteen per cent of the BEF’s total force, lost in one engagement. |

|---|---|

| b | St George had been the patron saint and protector of English armies since the 11th-century First Crusade.[6] |