The Atterbury Plot was a conspiracy named after Francis Atterbury, Bishop of Rochester and Dean of Westminster, aimed at restoring the House of Stuart to the throne of Great Britain. It was hatched six years after the unsuccessful Jacobite rebellion of 1715, at a time when the Whig government of the new Hanoverian king, George I, was deeply unpopular. Other conspirators included Charles Boyle, 4th Earl of Orrery, Lord North and Grey, Sir Henry Goring, Christopher Layer, John Plunkett, and the Reverend George Kelly, an Irish Protestant clergyman.

The plot, initiated early in 1721, was exposed the following year. Evidence against the conspirators proved difficult for the authorities to come by, so rather than being charged with treason, Atterbury was removed from his Church of England positions and sentenced to perpetual exile. Christopher Layer was not so lucky however, and was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quarteredStatutory penalty in England from 1352 for men convicted of high treason. , which he was on 17 May 1723.

Although the plot has been named after Atterbury, the biographer Lawrence B. Smith has observed that there were clearly several overlapping conspiracies rather than a single unified plot. Christopher Layer, in his deposition to the committee charged with investigating the plot, states emphatically that Orrery and North “had different schemes”.[1]

Background

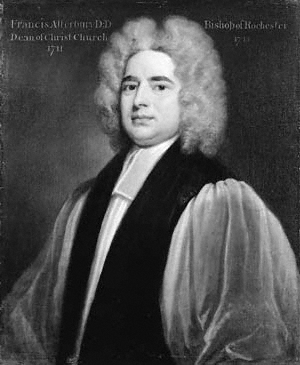

Atterbury was a Tory and a leader of the High Church party in the Church of England. In 1710, the prosecution of Henry Sacheverell led to an explosion of High Church fanaticism, and Atterbury helped Sacheverell with his defence, then became an active pamphleteer against the Whig ministry. When the ministry changed, rewards came to him. Queen Anne chose him as her chief adviser in church matters, and in August 1711 she appointed him Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, a strongly Tory college. In 1713 he was promoted to become Bishop of Rochester and Dean of Westminster Abbey, and if the Tories had remained in power he might have risen much higher, so he dreaded the Hanoverian accession planned by the Act of Settlement of 1701.[2]

The death of Queen Anne in 1714 was a setback for Atterbury. He took the oath of allegiance to George I, but became an opponent of the new government. He was in indirect communication with the family of the Pretender, James Francis Edward Stuart, and when the Jacobite Rising of 1715 appeared, he refused to sign a declaration in which other bishops supported the Protestant accession. In 1717 hundreds of Jacobites arrested at the time of the Rising were released from prison by the Act of Grace and Pardon, and Atterbury began to correspond directly with the Pretender.[2]

Events of 1720, notably the bursting of the South Sea Bubble, left the pro-Hanoverian Whig government in disarray and deeply unpopular with the many ruling-class investors who had lost heavily. Atterbury seized the moment to conspire with the exiled John Erskine, who at the Jacobite court was the Duke of Mar, and who had been the Pretender’s Secretary of State.[3]

Plot of 1721

The aim of the conspirators was a Jacobite rising to coincide with the general election expected in 1722, this date being foreseen because by the Septennial Act of 1716 parliament was enabled to sit for seven years after the election of 1715.[3]

Sir Henry Goring, who was himself standing (unsuccessfully as turned out) in the election as MP for his old seat of Steyning in Sussex, wrote to the Pretender on 20 March 1721, a letter in which he put forward a plan for a restoration of the Stuart monarchy with the assistance of an invasion by Irish exile troops commanded by the Duke of Ormonde[a]The Duke of Ormonde had replaced the Duke of Marlborough as Captain-General of the British forces.[4] from Spain and Lieutenant-General Dillon from France.[5]

Christopher Layer, a barrister of the Middle Temple and an agent and legal advisor to the “notorious Jacobite” Lord North and Grey,[6] met some fellow plotters regularly at an inn in Stratford-le-Bow, and by the summer of 1721 had succeeded in recruiting some soldiers at Romford and Leytonstone. He then travelled to Rome, where he met the Pretender to reveal the details of a plot. Layer stated that he represented a large number of influential Jacobites, who proposed to recruit old soldiers to seize the Tower of London, the Bank of England, the Royal Mint, and other government buildings in Westminster and the City of London, to capture the Hanoverian royal family, and to kill other key men. English Tories were to summon their men, secure their counties, and march on London, while volunteers from the Irish Brigade of the French Army were to land in England to join them. Layer returned to London with assurances of royal favour from the Pretender.[7]

The plot collapsed in England in early 1722, following the death of Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl of Sunderland, on 19 April, who a year before had been forced to resign as First Lord of the Treasury. The Duke of Orleans, Regent of France, made it known to Lord Carteret, Robert Walpole’s Secretary of State for the Southern Department, that the Jacobites had asked him to send three thousand men in support of a coup d’état to take place early in May. The French said they had refused permission for the Duke of Ormonde to march a force across France to a channel port, and they had also moved their Irish Brigade away from Dunkirk.[8]

Insufficient money had been raised by the Jacobites in England to provide enough arms to support a rising, leading Mar (writing in March 1722) to comment that Goring, “though a honest, stout, man, had not showed himself very fit for things of this kind.”[5]

Investigation and trial

Walpole’s agents could find very little evidence against the leading suspects, but Walpole nevertheless gave orders for several men to be arrested, including Orrery, North and Grey, Goring, Atterbury, the Duke of Mar’s agent George Kelly, and Christopher Layer. Atterbury, who had long been an opponent of Walpole, was named as a conspirator by Mar and was arrested on 24 August 1722, to be charged with treason.[9] He and Orrery were imprisoned in the Tower of London, and on 17 October the Habeas Corpus Act was suspended.[10]

Goring meanwhile had fled the country on 23 August; he remained in France until his death in 1731. In his absence, at a trial in which he was considered to be one of the major managers of the plot, his agent stated that Goring had attempted to enlist a gang of one thousand brandy smugglers to assist the proposed invasion.[5]

Layer was arrested and lodged with Atterbury in the Tower; his clerks were placed under surveillance, and his wife was arrested and brought to London from Dover. He was less fortunate than the other conspirators, as two women agreed to give evidence against him. His case was first heard at the Court of King’s Bench on 31 October 1722, and a trial began on 21 November before the Lord Chief Justice, John Pratt. Among compromising papers found in the possession of Elizabeth Mason, a brothel-keeper, was one entitled “Scheme”, said to be in Layer’s hand, which outlined a proposed insurrection. The court was interested to have evidence that the Pretender and his wife had acted as godparents to Layer’s daughter, when they were represented at a christening in Chelsea by the proxies Lord North and Grey and the Duchess of Ormonde. After a trial lasting eighteen hours, the jury unanimously found Layer guilty of high treason. On 27 November 1722, he was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quarteredStatutory penalty in England from 1352 for men convicted of high treason. , but execution was several times delayed, in the hope of his giving information against others, which he refused to do. The sentence was eventually carried out at Tyburn on 17 May 1723.[7]

Atterbury’s correspondence with the Jacobites in exile proved to have been so cautious that it was judged to be insufficient to lead to a conviction. He was therefore the target of a Pains and Penalties Bill, with the aim of removing him from his church positions, banishing him for life, and forbidding British subjects to communicate with him, by the decision of parliament rather than through prosecution in a court. In May 1723 the Bill was approved by the Commons and by the Lords, where the voting was eighty-three votes for and forty-three against,and it was enacted on 15 May, two days before Layer’s execution. On 18 June Atterbury went into exile in France.[2][11]

Orrery was released from the Tower in late September 1722 on bail of £50,000, following appeals from his family that ill health meant that his life was in danger.[12] North was undoubtedly implicated in the plot, having been commissioned by the Pretender as lieutenant-general and commander-in-chief for London and Westminster, but as no-one seemed willing to testify against him he was discharged on 28 October 1723 and retired to a life of exile in the Low Countries.[1] George Kelly succeeded in escaping from the Tower of London,[13] but along with Plunkett his estates were forfeited.[14]

Aftermath

Although the involment of Catholics in the Atterbury Plot was minimal – indeed Bishop Atterbury was openly hostile to most Catholics and disliked working with them – it was perhaps inevitable that any effort to restore the Stuart dynasty to the throne would be laid at their door.[15] Consequently the government decided to impose a levy of £100,000 – equivalent to about £15.3 million as at 2018[b]Calculated using the retail price index.[16] – on the entire Catholic community, to be paid on a county basis according to the wealth of the Catholics living there.[17]