Babs is the land-speed record car that was built and driven by John Parry-Thomas to a world land-speed record in 1926. The car began life as Chitty 4, one of the racing driver Count Louis Zborowski’s series of aero-engined Chitty Chitty Bang Bang cars; as it was built at Zborowski’s estate of Higham Park near Canterbury, it was also known as the Higham Special. Still not fully developed by the time of Zborowski’s death in 1924, it was purchased from his estate by the motor engineer and racing driver J. G. Parry-Thomas for £125, equivalent to about £6800 as at 2018.[1][a]Using the GDP deflator to compare the value of £125 in 1924 with 2018[2]

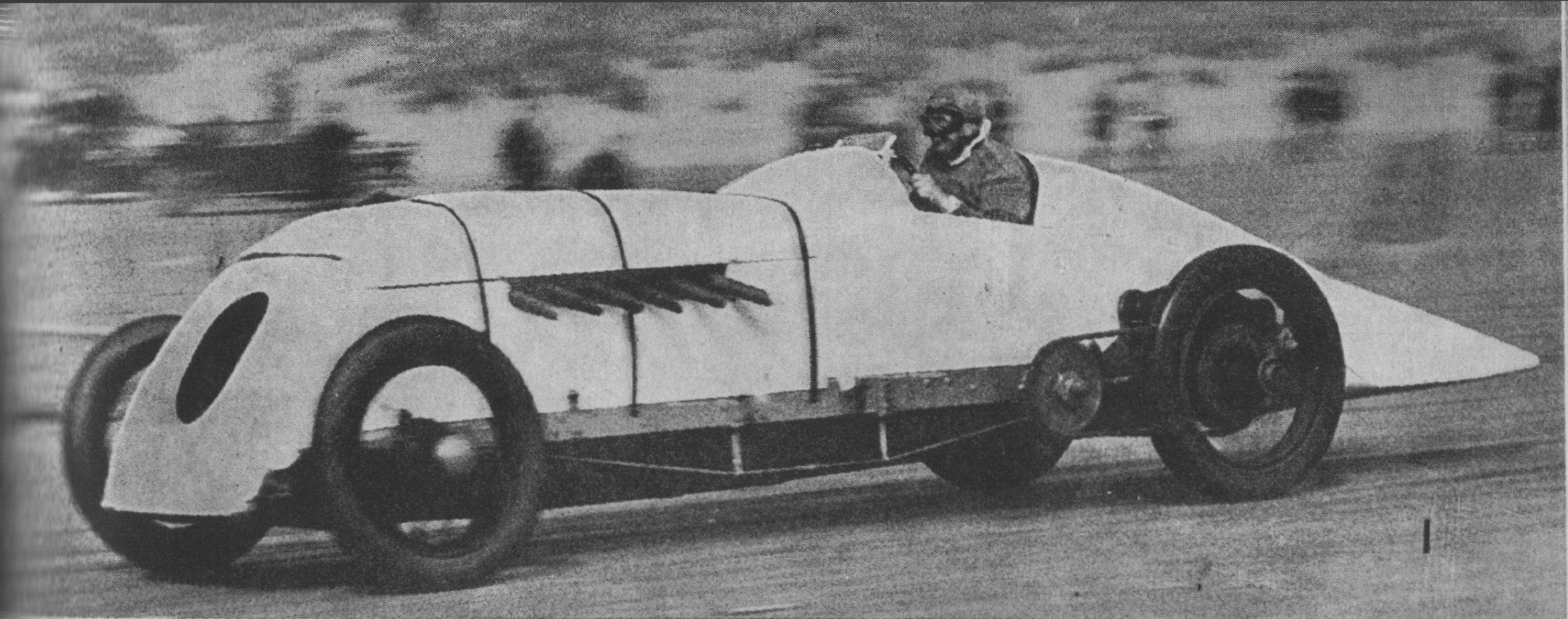

The car was fitted with a 450 hp (340 kW) V12 Liberty 27-litre American aero engine, with a gearbox and chain drive from a pre-war Blitzen Benz. Parry-Thomas rechristened the car Babs, after a friend’s daughter, and rebuilt it with four Zenith carburettors and his own design of pistons. On 28 April 1926 he drove the car to a new world land speed record of 171 mph (275 km/h)[3]

During a later record attempt at Pendine Sands, Wales on 3 March 1927, Parry-Thomas lost control of the car at a speed in excess of 100 mph (161 km/h); the car rolled over and Parry-Thomas was partially decapitated. Babs’ design made use of external chains (covered by cowlings) to transfer power to the drive wheels, and so at the time it was thought that one of the drive chains had snapped, decapitating the driver. But more recent investigation of the wreckage has led to the suggestion that the accident was caused by a failure of the rear right-hand wheel.[4]

Following the inquest into Parry-Thomas’s death – the first person to die in a land-speed record attempt – Babs was buried in the sand dunes at Pendine. Parry-Thomas himself was interred at St Mary’s Church, Byfleet, Surrey on 7 March 1927.[3] Reports that Babs was buried at the request of the dead driver are almost certainly untrue. More likely it was not thought to be worthwhile transporting the car back to Weybridge.[5]

Excavation

In 1967 the vintage vehicle restorer and lecturer in mechanical engineering Owen Wyn Owen decided to excavate and restore Babs. He managed to identify the site of the car’s burial from an old photograph hanging in a local pub,[6] but it was found to be within the perimeter of the present-day rocket establishment. The military authorities granted permission for the excavation on condition that Parry-Thomas’s next of kin did not object. It took Wyn Owen more than two years to locate a living relative, a nephew living in Walsall, but finally the wreck was recovered.[7] The recovery was controversial at the time, but less so after the successful restoration. The prevailing opinion was that the wreck would be unsalveagable for anything more than a museum display; few expected that it would ever resemble a car again, let alone be restored to running order.[5]

Wyn Owen’s ownership of Babs was in dispute for several years. Pendine Council, in whose area the car had been buried, only agreed to relinquish their claim in 1992 on the basis that the car was on display locally for ten weeks each summer, to boost tourism.[8] Consequently Babs was displayed every summer in the Pendine Museum of SpeedMuseum dedicated to the use of Pendine Sands for land speed record attempts. It opened in 1996 in the village of Pendine, on the south coast of Wales, and was owned and run by Carmarthenshire County Council. , until the museum’s closure for redevelopment in 2018.[9]

Restoration

The car was in very poor condition. Much of the bodywork had corroded, so a new body had to be constructed, incorporating where possible any existing original material. The mechanical running gear was in good condition though. Even when components could not be re-used, they were sufficiently preserved to act as a pattern. The engine was salvageable, but many new replacement parts had to be made from original designs.

A correspondent writing in Motor Sport magazine in 1969 who examined the excavated car reported that the cowling over the o/s chain – which the inquest of 1927 had concluded was the cause of Parry-Thomas’s decapitation – was intact, so his injuries were more likely the result of Babs rolling over after he had lost control of the car. He also measured the car’s dimensions, giving a wheelbase of 11 feet 6 inches (3.51 m) and an overall length of 20 feet 3 inches (6.17m).[10]

After ten years of work Wyn Owen had Babs running again. In 1999 he was awarded the Tom Pryce trophy for his work in restoring the car.[11]

Notes

| a | Using the GDP deflator to compare the value of £125 in 1924 with 2018[2] |

|---|