Wikimedia Commons

Bile Beans was a laxative and tonic first marketed in the 1890s.[1][2] The product supposedly contained substances extracted from a hitherto unknown vegetable source by a fictitious chemist known as Charles Forde.[3] In the early years Bile Beans were marketed as “Charles Forde’s Bile Beans for Biliousness”, and sales relied heavily on newspaper advertisements. Among other cure-all claims, Bile Beans promised to “disperse unwanted fat” and “purify and enrich the blood”.[4]

Although the manufacturer claimed that the formula for Bile Beans was based on a vegetable source known only to Aboriginal Australians, its actual ingredients, which included cascara, rhubarb, liquorice and menthol, were commonly found in pharmacies of the period. A court case initiated in Scotland in 1905 found that the Bile Bean Manufacturing Company’s business was based on a fraud and conducted fraudulently, but Bile Beans nevertheless continued to be sold until the 1980s.

Formulation and manufacture

Charles Edward Fulford (1870–1906) and Ernest Albert Gilbert (1875–1905) first sold Bile Beans in Australia in late 1897, marketed as “Gould’s Bile Beans”.[5] Fulford was a Canadian who had travelled to Australia to sell Dr. Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People for his uncle, George Taylor Fulford.[6][7]

Fulford and Gilbert established the Bile Bean Manufacturing Company in Leeds, England, in 1899. It was claimed that the formula for Bile Beans was created by an Australian scientist Charles Forde in 1898, based on research he had conducted on a vegetable source known only to Aboriginal Australians. In reality, Charles Forde did not exist; the name was used as an alias for Charles Fulford, who had no scientific training. The beans were initially manufactured in America by Parke Davis & Co. of Detroit, until the Bile Bean Manufacturing Company set up a production facility in Leeds, England,[8] trading under the name of C. E. Fulford Limited, which also sold other patent medicines, including the Zam-Buk ointment,[a] Zam-Buk was manufactured by the Zam-Buk Company of Leeds, another of Charles Fulford’s enterprises.[8] Pep pastilles and later Vitapointe hair conditioner.[1][b]The principle production plant moved to Blyth, Northumberland in 1963.[9]

The product sold by Fulford and Gilbert was not the first patent medicine marketed as “Bile Beans”. A different type of Bile Beans was invented by James F. Smith, a chemist from Texarkana, Texas, in the 1870s or 1880s, and J.F. Smith & Co traded out of St Louis, Mo. The firm also produced a product called “Smith’s Blood Beans”, claimed to “purify the blood” and was “put up in packages similar to Bile Beans” with “sugar coating blood red in color”, and a “wrapper … lithographed in red ink instead of black”.[10] In 1902 the Bile Bean Manufacturing Company acquired the trade mark of “J. F. Smith’s Bile Beans” in the UK, which had been registered in 1887.[11]

According to a 1903 report published in the British Medical Journal, the chief ingredients of Bile Beans were cascara, rhubarb, liquorice and menthol, packaged as a gelatine-coated pill,[12] all ingredients commonly found in pharmacies of the period.[13] It was not until 1941 that English companies were legally required to disclose the active ingredients in their non-prescription drugs.[14] By the 1940s, the ingredients included various purgatives, cholagogues, and carminatives, including aloin (aloe), Podophyllum, cascara, scammony, jalap, colocynth, leptandrin, saponis (soap), cardamom, capsicum, ginger, peppermint oil, and gentian, mixed with liquorice, powdered gum (acacia or tragacanth) and glucose, coated with black charcoal or carbon powder to form ovoid pills.[15]

Findings of fraud

In 1905 the Bile Beans Manufacturing Company initiated a passing off court case in Scotland against an Edinburgh chemist, George Graham Davidson, who sold “Davidson’s Bile Beans”, seeking to prevent him from selling any product using the name “bile beans” except that supplied by the company. The presiding judge, Lord Ardwall, rejected the case, as he considered that the plaintiff’s business was “founded on, and conducted by fraud”, there being no secret ingredient and no connection with any plant found in Australia.[13][16] The Court of Session dismissed an appeal, because it considered that the Bile Bean Manufacturing Company had deliberately defrauded the public by making false factual statements about the product, concluding that it was not entitled to any legal protection against the use of the term “bile beans”.[11]

Marketing strategy

After setting up in England in 1899 the company spent about £60,000 a year in advertising its products,[8] and according to Birmingham University Professor of Medicine Robert Saundby,[17] “created a demand by flooding the country with advertisements, placards, pamphlets and imaginary pictures.”[18] Early newspaper promotions usually took the form of testimonials proclaiming “miraculous life changing cures”.[19] Often illustrated, they included letters from customers cured of lost appetites, severe headaches, indigestion and biliousness.[20] A half-page advertisement in the Sheffield Evening Telegraph on 12 October 1900 featured a lady who had been cured by Bile Beans after ten doctors had failed to successfully treat her condition; copies of signed affidavits from neighbours were also printed.[21] The level of advertising was not curtailed despite the adverse comments made by the judges in the court ruling.[22]

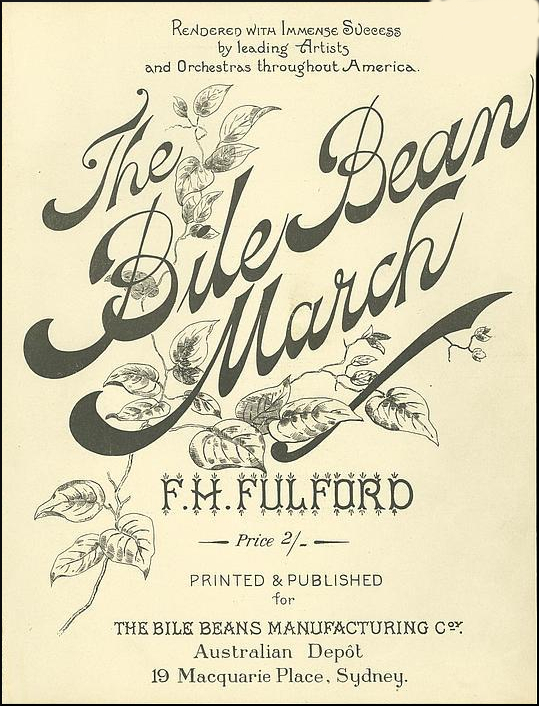

Among the more unusual marketing promotions undertaken by the Bile Beans Manufacturing Company was the “Bile Bean March”, composed by Charles Fulford’s older brother Frank Harris FulfordCanadian-born entrepreneur, art collector and businessman and first published in 1898.[6][23] The music was described as “a bold, spirited composition” in a 1902 newspaper report.[24] Readers could apply to receive a free copy of the sheet music by sending their address details to the company.[25] Another marketing ploy was the production of a cookery book,[23] which was also made widely available free of charge.[19] A Bile Bean Puzzle Book was published during the early 1930s and also freely distributed.[26] By that time advertising for Bile Beans had become increasingly targeted at women, promising them health, bright eyes and a slim figure if taken regularly.[19]

When Radio Luxembourg started longwave commercial radio broadcasts in English in 1933, its first advertisers were Fulford’s Bile Beans and Zam-Buk.[27]

During the 1940s newspaper advertising was supplemented by a poster campaign. Aimed at maintaining high levels of purchasing by women, the posters featured young ladies dressed to participate in various activities, including horse riding, swimming and hiking;[23] the designs were the work of S. H. Benson,[28] a London advertising agency whose clients included Bovril and Guinness.[29] The Bulletin of the North Carolina State Board of Health hypothesised in 1916–17 that many provincial newspapers relied heavily on the revenues generated by advertisements from manufacturers of suspect remedies, and it speculated that editorial control had been applied to restrict extensive reporting of the Bile Beans court case.[30] Similar suspicions had been raised almost ten years earlier by medical director Eric Pritchard,[31] who went on to highlight a clause showing newspaper advertising contracts could be revoked if the publication carried any material considered “detrimental to the Company’s interest”.[32]

Later history

Gilbert died in 1905 and Charles Fulford the following year in Australia, aged 36, after which the business was run by Charles’s older brother, Frank Harris Fulford.[6][23] Charles’s estate was valued at £1.3 million, around £128 million today. He made several bequests which included the gift of twenty per cent of the company shares to the British charity Barnardo’s, although this conditional donation sparked consternation.[33] The clauses stipulated the charity must set up a limited company that would only sell Bile Beans and patent medicines manufactured by Fulford’s businesses; additionally, Barnardo’s were forbidden to sell any of the shares. A writer in the British Medical Journal suggested that the bequest presented the charity with an ethical dilemma, as it enjoyed the patronage from medical and religious professions, and trading in products described by a judge as fraudulent would be perpetuating the deception.[34] Initially Barnardo’s refused the gift but eventually accepted an unconditional lump sum.[35]

Despite the Bile Beans Manufacturing Company having lost the Scottish court case in 1906, Bile Beans remained popular through the 1930s, and continued to be sold until the 1980s.[2] The business was so successful that Frank Fulford was able to purchase Headingley Castle in Leeds in 1909, and donate artworks to the museum at Temple Newsam.[19]