Wikimedia Commons

Black Friday was a suffragette demonstration in London on 18 November 1910, in which 300 women marched to the Houses of Parliament as part of their campaign to secure voting rights for women. The day became so-called because of the violence meted out to protesters, some of it sexual, by the Metropolitan Police and male bystanders.

During the January 1910 general election campaign, the Prime Minister and leader of the Liberal Party H. H. Asquith promised to introduce a Conciliation Bill to allow a measure of women’s suffrage in national elections. On his return to power a committee made up of pro-women’s suffrage MPs from several political parties was formed, which proposed legislation that would have added a million women to the franchise. The suffrage movement supported the legislation, but although MPs backed the bill and passed its first and second readings, Asquith refused to grant it further parliamentary time. On 18 November 1910, following a breakdown in relations between the House of Commons and House of Lords over that year’s budget, Asquith called another general election, declaring that parliament would be dissolved on 28 November.

The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) saw the move as a betrayal, and organised a protest march to parliament from Caxton Hall in Westminster. Lines of police and crowds of male bystanders met three hundred female protestors outside the Houses of Parliament; the women were attacked for the next six hours. Many women complained about the sexual nature of the assaults, which included having their breasts twisted and pinched. Police arrested 4 men and 115 women, although all charges were droppedthe following day. The conciliation committee was angered by the accounts, and undertook interviews with 135 demonstrators, nearly all of whom described acts of violence against the women; 29 of the statements included details of sexual assault. Calls for a public inquiry were rejected by Winston Churchill, then Home Secretary.

The violence may have caused the subsequent deaths of two suffragettes. The demonstration led to a change in approach; many members of the WSPU were unwilling to risk being subjected to similar violence, so they resumed their previous forms of direct action such as throwing stones and breaking windows, which afforded time to escape. The police also changed their tactics; during future demonstrations they tried not to arrest too soon or too late.

Background

Women’s Social and Political Union

The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was formed in 1903 by the political activist Emmeline Pankhurst. From around 1905 – following the failure of a private member’s bill to introduce the vote for women – the organisation increasingly began to use militant direct action to campaign for women’s suffrage.[1][2][a]The first such act was in October 1905, when Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney interrupted a political rally in Manchester to ask the pro-women’s suffrage Liberal Party politician Sir Edward Grey “Will the Liberal government give votes to women?” The two women were arrested for assault and obstruction; on refusing to pay the fines levied against them, they were sent to prison.[3] According to the historian Caroline Morrell, from 1905 “The basic pattern of WSPU activities over the next few years had been established – pre-planned militant tactics, imprisonment claimed as martyrdom, publicity and increased membership and funds.”[4]

From 1906 WSPU members adopted the name suffragettes, to differentiate themselves from the suffragists of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, who employed constitutional methods in their campaign for the vote.[1][5][b]Charles E. Hands, the Daily Mail journalist, coined the name suffragettes to belittle members of the WSPU in 1906, but they adopted the label with pride.[5][6] From 1907 WSPU demonstrations faced increasing police violence.[7] Sylvia Pankhurst – the daughter of Emmeline and a member of the WSP – described a demonstration in which she took part in February that year:

Wikimedia Commons

After one demonstration in June 1908 in which “roughs appeared, organised gangs, who treated the women with every type of indignity”,[9] Sylvia Pankhurst complained that “the ill-usage by the police and the roughs was greater than we had hitherto experienced”.[9] During a demonstration in June 1909 a deputation tried to force a meeting with H. H. Asquith, the Prime Minister; 3000 police provided tight security to prevent the women from entering parliament, arresting 108 women and 14 men.[10][11] Following the police violence used on that occasion, the WSPU began shifting to a strategy of breaking windows rather than attempting to rush into parliament. Sylvia Pankhurst wrote that “Since we must go to prison to obtain the vote, let it be the windows of the Government, not the bodies of women which shall be broken, was the argument”.[12][c]The women arrested for window breaking began a hunger strike to be treated as First Division prisoners – reserved for political crimes – rather than Second or Third Division, the classifications for common criminals. They were released early, rather than being reclassified. First Division prisoners had open access to books and writing equipment, did not have to wear prison uniforms and could receive visitors. Prisoners in the Second and Third Divisions were managed under more restrictive regulations.[13][14]

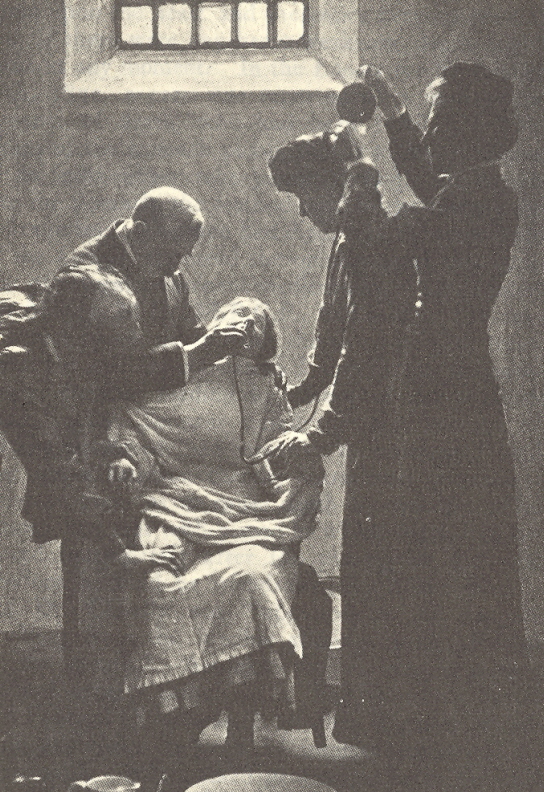

At a demonstration in October 1909 – at which the WSPU again attempted to rush into parliament – ten demonstrators were taken to hospital. The suffragettes did not complain about the rising level of police violence. Constance Lytton wrote that “the word went round that we were to conceal as best we might, our various injuries. It was no part of our policy to get the police into trouble.”[15] The level of violence in suffragette action increased throughout 1909. Bricks were thrown at the windows of Liberal Party meetings; Asquith was attacked while leaving church; and roof tiles were thrown at police when another political rally was interrupted. Public opinion turned against the tactics and, according to Morrell, the government capitalised on the shift in public feeling to introduce stronger measures. Thus, in October 1909, Herbert Gladstone, the Home Secretary, instructed that all prisoners on hunger strike should be force fed.[16]

Political situation

Wikimedia Commons

The Liberal government elected in 1905 was a reforming one which introduced legislation to combat poverty, deal with unemployment and establish pensions. The Conservative Party-dominated House of Lords impeded much of the legislation.[18][d]According to the historian Bruce Murray, many of the measures introduced by the government were “mangled by amendments or rejected outright” by the House of Lords;[19] ten parliamentary bills sent to them from the Commons were rejected by the Lords, who also amended more than 40 per cent of the legislation they received.[20] In 1909 the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, introduced the so-called People’s Budget, which had the expressed intent of redistributing wealth among the population.[21] This budget was passed by the House of Commons, but rejected by the Lords.[e]The rejection of the budget was a breach of the constitutional convention that the House of Lords was not supposed to interfere in financial bills from the House of Commons.[21] As a result, on 3 December 1909, Asquith called a general election for the new year to obtain a fresh mandate for the legislation.[18][22] As part of the campaigning for the January 1910 election, Asquith – a known anti-suffragist – announced that should he be re-elected, he would introduce a Conciliation Bill to introduce a measure of female suffrage. The proposal was dismissed by suffrage campaigners as being unlikely to materialise.[23] The election produced a hung parliament, with the Liberals’ majority eliminated; although they won the largest number of seats, they returned only two more MPs than the Conservative Party. Asquith retained power after he was able to form a government with the support of the Irish Parliamentary Party.[24][f]The Conservative and Liberal Unionists gained 272 seats (up 116 from the previous parliament); the Liberals won 274 seats (down 123); the Irish Parliamentary Party won 71 (down 11) and Labour won 40 (up 11).[25]

On 31 January 1910, in response to Asquith’s statement, Pankhurst announced that the WSPU would pause all militant activity and focus on constitutional activities only.[26] For six months the suffrage movement went into a propaganda drive, organising marches and meetings, and local councils passed resolutions supporting the bill.[27] When the new Parliament convened, a cross-party conciliation committee of pro-women’s suffrage MPs was formed under the chairmanship of Lord Lytton, the brother of Lady Constance Bulwer-Lytton.[28][29][g]The committee was composed of 25 Liberal MPs, 17 Conservative MPs, 6 Irish Nationalist MPs and 6 Labour MPs.[28] They proposed legislation that would have enfranchised female householders and those women who occupied business premises; the bill was based on existing franchise laws for local government elections, under which some women had been able to vote since 1870.[30][h]The terms of the Conciliation Bill, officially named “A Bill to Extend the Parliamentary Franchise to Women Occupiers” were that the franchise should be extended to: Every woman possessed of a household qualification, or of a ten-pound occupation qualification, within the meaning of the Representation of the People Act 1884, shall be entitled to be registered as a voter, and, when registered, to vote for the county or borough in which the qualifying premises are situate. For the purposes of this Act, a woman shall not be disqualified by marriage for being registered as a voter, provided that a husband and wife shall not both be qualified in respect of the same property.[31] £10 in 1910 equates to approximately £900 in 2018 pounds, according to calculations based on Retail Price Index measure of inflation.[32]

The measure would have added approximately a million women to the franchise; it was kept to a relatively small number to make the bill as acceptable as possible to MPs, mostly Conservatives.[33] Although the WSPU thought the scope of the bill too narrow – it excluded women lodgers and most wives and working-class women – they accepted it as an important stepping stone.[27][34]

The Conciliation Bill was introduced into Parliament as a private members bill on 14 June 1910.[35][36] The question of women’s suffrage was divisive within Cabinet, and the bill was discussed at three separate meetings.[37] At a Cabinet meeting on 23 June, Asquith stated that he would allow it to pass to the second reading stage, but no further parliamentary time would be allocated to it and it would therefore fail.[38] Nearly 200 MPs signed a memorandum to Asquith asking for additional parliamentary time to debate the legislation, but he refused.[39] The bill received its second reading on 11 and 12 July, which it passed 299 to 189. Both Churchill and Lloyd George voted against the measure; Churchill called it “anti-democratic”.[35] At the end of the month Parliament was prorogued until November.[40] The WSPU decided to wait until Parliament reconvened before they decided if they were to return to militant action. They further decided that if no additional parliamentary time was given over to the Conciliation Bill, Christabel Pankhurst would lead a delegation to Parliament, demand the bill be made law, and refuse to leave until that was done.[35] On 12 November the Liberal Party politician Sir Edward Grey announced that there would be no further parliamentary time given to the conciliation legislation that year. The WSPU announced that in protest they would undertake a militant demonstration to Parliament when it reconvened on 18 November.[41]

18 November

Wikimedia Commons

On 18 November 1910, in an attempt to resolve the parliamentary impasse arising from the House of Lords veto on Commons legislation, Asquith called a general election, and said that parliament would be dissolved on 28 November; all remaining time was to be given over to official government business. He did not refer to the Conciliation Bill.[42] At noon on the same day the WPSU held a rally at Caxton Hall, Westminster. The event had been widely publicised, and the national press was prepared for the expected demonstration later in the day.[43] From Caxton Hall, approximately 300 members – divided into groups of ten to twelve by the WSPU organiser Flora Drummond – marched to parliament to petition Asquith directly.[44][45][i]Sylvia Pankhurst, in her history of the women’s militant suffrage movement, puts the number at 450 demonstrators.[46] The deputation was led by Emmeline Pankhurst. The delegates in the lead group included Dr Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson, Hertha Ayrton and Princess Sophia Duleep Singh.[47][j]Elizabeth Garrett Anderson was the first woman to openly qualify in Britain as a physician and surgeon; Louisa Garrett Anderson, her daughter, was a surgeon; Hertha Ayrton was an engineer and mathematician; Sophia Duleep Singh was a Punjabi princess whose godmother was Queen Victoria.[47] The first group arrived at St Stephen’s entrance at 1:20 pm.[48] They were taken to Asquith’s office where his private secretary informed them that the prime minister refused to see them. They were escorted back to St Stephen’s entrance, where they were left to watch the demonstration.[49]

Previous demonstrations at the Houses of Parliament had been policed by the local A Division, who understood the nature of the demonstrations and had managed to overcome the WSPU tactics without undue levels of violence.[50] Sylvia Pankhurst wrote that “During our conflicts with the A Division they have gradually come to know us, and to understand our aims and objects, and for this reason, whilst obeying their orders, they came to treat the women, as far as possible, with courtesy and consideration”.[51] On the day of the demonstration, police had been drafted in from Whitechapel and the East End; these men were inexperienced in policing suffragettes.[52][53] Sophia van Wingerden, in her history of the women’s suffrage movement, writes that “the differing accounts of the event of that day make it difficult to determine the truth about what happened”;[54] Morrell similarly observes that the government, the press and the demonstrators all provide markedly different accounts.[55]

Groups approaching Parliament Square were met at the Westminster Abbey entrance to the square by groups of bystanders, who manhandled the women. As they moved past the men, the suffragettes were met by lines of policemen who, instead of arresting them, subjected them to violence and insults, much of which was sexual in nature. The demonstration continued for six hours; police beat women attempting to enter parliament, then threw them into the crowds of onlookers, where they were subjected to further assaults.[1][56][57][58] Many of the suffragettes considered that the crowds of men who also assaulted them were plain-clothes policemen.[59] Caxton Hall was used throughout the day as a medical post for suffragettes injured in the demonstration. Sylvia Pankhurst recorded that “We saw the women go out and return exhausted, with black eyes, bleeding noses, bruises, sprains and dislocations. The cry went round: ‘Be careful; they are dragging women down the side streets!’ We knew this always meant greater ill-usage.”[60] One of those taken down a side street was Rosa May Billinghurst, a disabled suffragette who campaigned from a wheelchair. Police pushed her chair into a side road, assaulted her and stole the valves from the wheels, leaving her stranded.[61] The historian Harold Smith writes “it appeared to witnesses as well as the victims that the police had intentionally attempted to subject the women to sexual humiliation in a public setting to teach them a lesson”.[56]

Following days

On 18 November, 4 men and 115 women were arrested.[49][62] The following morning, when they were appeared at Bow Street Police Court, the prosecution stated that Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, had decided that on the grounds of public policy “on this occasion no public advantage would be gained by proceeding with the prosecution”; all charges were dropped.[63] Katherine E. Kelly, in her examination of how the media reported the suffrage movement in the early 20th century, considers that by dropping the charges against the demonstrators Churchill implemented “a tacit quid pro quo … [in which] he refused to inquire into the charges of police brutality”.[64][65] On 22 November Asquith announced that should the Liberals be returned to power at the next election, there would be parliamentary time for a Conciliation Bill to be put to parliament. The WSPU were angered that his promise was for within the next parliament, rather than the next session, and 200 suffragettes marched on Downing Street, where scuffles broke out with the police; 159 women and 3 men were arrested. The following day another march on parliament was met with a police presence, and 18 demonstrators were arrested. Charges against many of those arrested on 22 and 23 November were subsequently dropped.[66][67]

Reaction

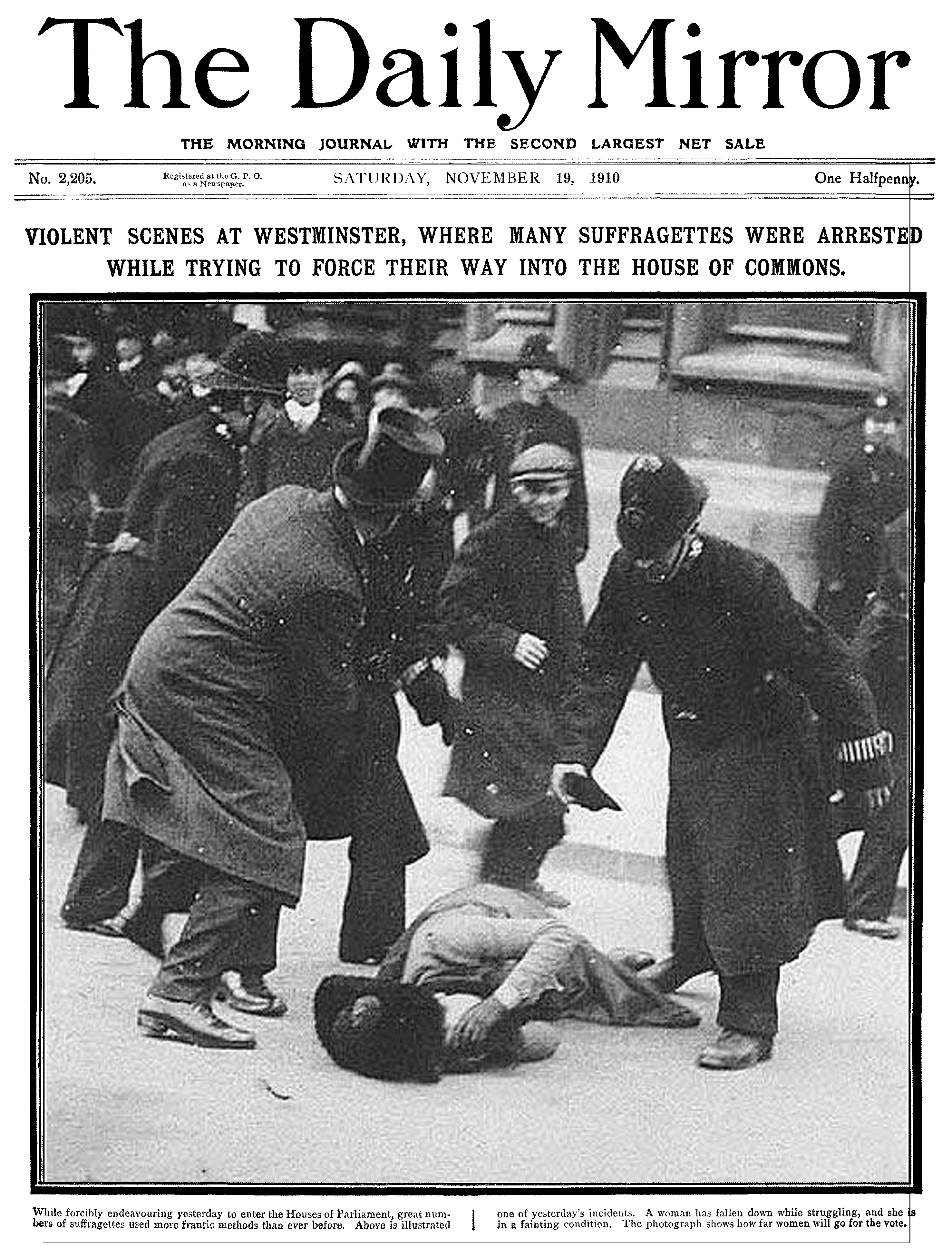

On 19 November 1910, newspapers reported on the events of the previous day. According to Morrell they “almost unanimously refrained from any mention of police brutality”, and focused instead on the behaviour of the suffragettes.[68] The front page of The Daily Mirror that day showed a large photograph of a suffragette on the ground, having been hit by a policeman during Black Friday; the image is probably that of Ada Wright.[69][70][k]Wright was identified by Georgiana Solomon in Votes for Women[71] and Sylvia Pankhurst in her book The Suffragette Movement (1931).[72] The National Archives identify the woman as possibly being Ernestine Mills.[73] The art editor of the newspaper forwarded the photograph to the Commissioner of Metropolitan Police for comments. He initially tried to explain the image away by saying the woman had collapsed through exhaustion.[74][75] The image was also published in Votes for Women,[51] The Manchester Guardian[76] and the Daily Express.[77]

Morrell observes that where sympathy was shown by newspapers, it was directed towards the policemen. The Times reported that “Several of the police had their helmets knocked off in carrying out their duty, one was disabled by a kick on the ankle, one was cut on the face by a belt, and one had his hand cut”;[68] The Daily Mirror wrote that “the police displayed great good temper and tact throughout and avoided making arrests, but as usual many of the Suffragettes refused to be happy until they were arrested … in one scuffle a constable got hurt and had to be led limping away by two colleagues.”[68] References to the suffragettes were in tones of disapproval for their actions; after Churchill decided not to prosecute the suffragettes, some newspapers criticised his decision.[78]

On 3 March Georgiana Solomon – a suffragette who had been present at the demonstration – wrote to The Times to say that police had assaulted her. She had been bed-ridden after their manhandling, and had not been able to make a complaint at the time. Instead, she had written to Churchill on 17 December with a full statement of what she had suffered, and the actions she had witnessed against others. She had received a formal acknowledgement, but no further letter from the government on the events. Her letter to Churchill had been printed in full in the suffragette newspaper Votes for Women.[79][80][81]

The WSPU leadership were convinced that Churchill had given the police orders to manhandle the women, rather than arrest them quickly. Churchill denied the accusation in the House of Commons and was so angered he considered suing Christabel Pankhurst and The Times, who had reported the claim, for libel.[82][l]Rosen gives as examples the suffragette newspaper Votes for Women of 25 November 1910, which stated that “The orders of the Home Secretary were, apparently, that the police were to be present both in uniform and in the crowd and that the women were to be thrown from one to the other”.[83] The 25 November 1910 edition of Votes for Women stated that “The orders of the Home Secretary were, apparently, that the police were to be present both in uniform and in the crowd and that the women were to be thrown from one to the other”.[83] In her biography of Emmeline Pankhurst, June Purvis writes that the police followed Churchill’s orders to refrain from making arrests;[84] the historian Andrew Rosen considers that Churchill had not given any orders to the police to manhandle the demonstrators.[85]

Murray and Brailsford report

When members of the conciliation committee heard the stories of the demonstrators’ maltreatment, they demanded a public inquiry, which was rejected by Churchill. The committee’s secretary – the journalist Henry Brailsford – and the psychotherapist Jessie Murray collected 135 statements from demonstrators, nearly all of which described acts of violence against the women; 29 of the statements also included details of violence that included indecency.[86][87] The memorandum they published summarised their findings:

A woman, who gave her name as Miss H, stated that “One policeman … put his arm round me and seized my left breast, nipping it and wringing it very painfully, saying as he did so, ‘You have been wanting this for a long time, haven’t you'”;[89] the American suffragette Elisabeth Freeman reported that a policeman grasped her thigh. She stated “I demanded that he should cease doing such a hateful action to a woman. He said, ‘Oh, my old dear, I can grip you wherever I like to-day'”;[90] and another said “the policeman who tried to move me on did so by pushing his knees in between me from behind, with the deliberate intention of attacking my sex”.[91]

On 2 February 1911 the memorandum prepared by Murray and Brailsford was presented to the Home Office, along with a formal request for a public inquiry. Churchill again refused.[92] On 1 March, in response to a question in parliament, he informed the House of Commons that the memorandum:

{{qiote|… contains a large number of charges against the police of criminal misconduct, which, if there were any truth in them, should have been made at the time and not after a lapse of three months … I have made inquiry of the Commissioner [of Metropolitan Police] with regard to certain general statements included in the memorandum and find them to be devoid of foundation. There is no truth in the statement that the police had instructions which led them to terrorise and maltreat the women. On the contrary, the superintendent in charge impressed upon them that as they would have to deal with women, they must act with restraint and moderation, using no more force than might be necessary, and maintaining under any provocation they might receive, control of temper.[93]}}

Impact

The deaths of two suffragettes have been attributed to the treatment they received on Black Friday.[94] Mary Clarke, Emmeline Pankhurst’s younger sister, was present at both Black Friday and the demonstration in Downing Street on 22 November. After a month in prison for breaking windows in Downing Street, she was released on 23 December and died on Christmas Day of a brain haemorrhage, age 48. Emmeline blamed her death on the maltreatment Clarke received at the two November demonstrations;[1][95] Murray and Brailsford wrote that “we have no evidence which directly connects the death of Mrs Clarke” to the demonstrations.[96] The second victim the WSPU claimed had died from maltreatment was Henria Williams. She had given evidence to Brailsford and Murray that “One policeman after knocking me about for a considerable time, finally took hold of me with his great strong hands like iron just over my heart … I knew that unless I made a strong effort … he would kill me”.[90] Williams died of a heart attack on 1 January 1911;[97] Murray and Brailsford wrote “there is evidence to show that Miss Henria Williams … had been used with great brutality, and was aware at the time of the effect upon her heart, which was weak”.[96]

The events that took place between 18 and 25 November had an impact on the WSPU membership, many of whom no longer wanted to take part in the demonstrations. The deputations to parliament were stopped, and direct action, such as stone throwing and window breaking became more common, affording women a chance to escape before the police could arrest them.[56][98] The historian Elizabeth Crawford considers the events of Black Friday determined the “image of the relations between the two forces and mark a watershed in the relationship between the militant suffrage movement and the police”.[99] Crawford identifies a change in the tactics used by the police after Black Friday. Sir Edward Troup, the under-secretary at the Home Office, wrote to the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in January 1911 to say that “I think there can be no doubt that the least embarrassing course will be for the police not to arrest too soon or defer arresting too long”, which became the normal procedure adopted.[100]

On 17 November 2010 a vigil called “Remember the Suffragettes” took place on College Green, Parliament Square “in honour of direct action”.[101]

Notes

| a | The first such act was in October 1905, when Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney interrupted a political rally in Manchester to ask the pro-women’s suffrage Liberal Party politician Sir Edward Grey “Will the Liberal government give votes to women?” The two women were arrested for assault and obstruction; on refusing to pay the fines levied against them, they were sent to prison.[3] |

|---|---|

| b | Charles E. Hands, the Daily Mail journalist, coined the name suffragettes to belittle members of the WSPU in 1906, but they adopted the label with pride.[5][6] |

| c | The women arrested for window breaking began a hunger strike to be treated as First Division prisoners – reserved for political crimes – rather than Second or Third Division, the classifications for common criminals. They were released early, rather than being reclassified. First Division prisoners had open access to books and writing equipment, did not have to wear prison uniforms and could receive visitors. Prisoners in the Second and Third Divisions were managed under more restrictive regulations.[13][14] |

| d | According to the historian Bruce Murray, many of the measures introduced by the government were “mangled by amendments or rejected outright” by the House of Lords;[19] ten parliamentary bills sent to them from the Commons were rejected by the Lords, who also amended more than 40 per cent of the legislation they received.[20] |

| e | The rejection of the budget was a breach of the constitutional convention that the House of Lords was not supposed to interfere in financial bills from the House of Commons.[21] |

| f | The Conservative and Liberal Unionists gained 272 seats (up 116 from the previous parliament); the Liberals won 274 seats (down 123); the Irish Parliamentary Party won 71 (down 11) and Labour won 40 (up 11).[25] |

| g | The committee was composed of 25 Liberal MPs, 17 Conservative MPs, 6 Irish Nationalist MPs and 6 Labour MPs.[28] |

| h | The terms of the Conciliation Bill, officially named “A Bill to Extend the Parliamentary Franchise to Women Occupiers” were that the franchise should be extended to: Every woman possessed of a household qualification, or of a ten-pound occupation qualification, within the meaning of the Representation of the People Act 1884, shall be entitled to be registered as a voter, and, when registered, to vote for the county or borough in which the qualifying premises are situate. For the purposes of this Act, a woman shall not be disqualified by marriage for being registered as a voter, provided that a husband and wife shall not both be qualified in respect of the same property.[31] £10 in 1910 equates to approximately £900 in 2018 pounds, according to calculations based on Retail Price Index measure of inflation.[32] |

| i | Sylvia Pankhurst, in her history of the women’s militant suffrage movement, puts the number at 450 demonstrators.[46] |

| j | Elizabeth Garrett Anderson was the first woman to openly qualify in Britain as a physician and surgeon; Louisa Garrett Anderson, her daughter, was a surgeon; Hertha Ayrton was an engineer and mathematician; Sophia Duleep Singh was a Punjabi princess whose godmother was Queen Victoria.[47] |

| k | Wright was identified by Georgiana Solomon in Votes for Women[71] and Sylvia Pankhurst in her book The Suffragette Movement (1931).[72] The National Archives identify the woman as possibly being Ernestine Mills.[73] |

| l | Rosen gives as examples the suffragette newspaper Votes for Women of 25 November 1910, which stated that “The orders of the Home Secretary were, apparently, that the police were to be present both in uniform and in the crowd and that the women were to be thrown from one to the other”.[83] |

References

- p. 729

- pp. 49–52

- p. 16

- p. 452

- p. 18

- loc. 5003–5017

- loc. 5591

- pp. 86–87

- loc. 2709–2722

- loc. 6011

- pp. 120–121

- p. 17

- p. 50

- p. 21

- p. 162

- p. 5

- p. 409

- p. 6

- pp. 161–162

- p. 118

- pp. 20–21

- p. 212

- p. 22

- loc. 3545

- pp. 70–71

- p. 71

- p. 144

- p. 23

- pp. 1202–1207

- p. 140

- p. 219

- p. 159

- loc. 3795, 3881

- p. 226

- pp. 108–109

- p. 166

- loc. 3985

- p. 164

- p. 502

- loc. 6630

- p. 33

- p. 1984

- p. 121

- p. 109

- loc. 4227

- p. 123

- p. 32

- p. 50

- p. 121

- p. 180

- p. 167

- loc. 6656

- p. 169

- p. 124

- p. 350

- p. 30

- pp. 151–152

- pp. 45–46

- p. 39

- p. 16

- p. 327

- p. 3

- loc. 4098

- pp. 16–17

- pp. 328–329

- p. 40

- pp. 1–5

- p. 10

- p. 241

- p. 117

- p. 150

- p. 140

- pp. 109–110

- loc. 4451

- p. 9

- p. 139

- p. 111

- p. 5

- p. 112

- pp. 367–368

- p. 112

- loc. 4168–4325

- p. 6

- p. 113

- loc. 4256

- p. 491

- p. 492

- p. 2