The National Archives

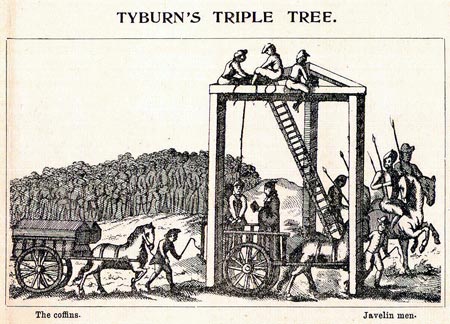

The Bloody Code is a name given to the system of crimes and punishments in force in England during the 18th and early 19th centuries that resulted in the death penalty for offences that would today be considered minor, such as cutting down a tree.[2] In 1688 there were fifty offences on the statute book punishable by death, but that number had almost quadrupled by 1776,[3] and it had reached 220 by the end of the century.[4] Most of the new laws introduced during that period were concerned with the defence of property, which some commentators have interpreted as a form of class suppression of the poor by the rich.[5] George Savile, 1st Marquess of Halifax, expressed a contemporary view when he said that “Men are not hanged for stealing horses, but that horses may not be stolen”.[6]

Grand larceny was one of the crimes that drew the death penalty, defined as the theft of goods worth more than 12 pence, about one-twentieth of the weekly wage for a skilled worker at the time. As the 18th century proceeded, juries often deliberately under-assessed the value of stolen goods to avoid a mandatory death sentence being imposed.[7]

Transportation

As the 17th century drew to a close, lawmakers sought a less harsh punishment that might still deter potential offenders; penal transportation with a term of indentured servitude became the more common punishment. This trend was continued by the Transportation Act 1717 (16 Geo. 3 c.43), which regulated and subsidised the practice, until its use was suspended by the Criminal Law Act 1776.[8] With the American Colonies already in active rebellion, parliament claimed its continuance “is found to be attended with various inconveniences, particularly by depriving this kingdom of many subjects whose labour might be useful to the community, and who, by proper care and correction, might be reclaimed from their evil course”. This law became known as the Hard Labour Act and the Hulks Act for both its purpose and its result. Its removal of the transportation alternative to the death penalty prompted the use of prisons for punishment and the start of prison-building programmes.[9] In 1785 Australia was deemed to be a suitably desolate place for convicts and transportation was resumed, now to a specifically planned penal colony. It has been estimated that more than one-third of all criminals convicted between 1788 and 1867 were transported to Australia, including to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania).

Jurist William Blackstone said of the Bloody Code:

Relaxation

The Judgement of Death Act 1823 made the death penalty discretionary for all crimes except treason and murder. Gradually during the middle of the 19th century, the number of capital offences was reduced, and by 1861 it was down to five:

- Murder

- Arson in a naval dockyard

- Espionage

- Piracy

- High treason

The last execution in the UK took place in 1964, and the death penalty for murder in Great Britain was abolished by the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act 1965; the death penalty for murder in Northern Ireland was not abolished until 1973. The death penalty was not finally abolished in the United Kingdom until 1998, by the Human Rights Act and the Crime and Disorder Act.