Wikimedia Commons

Carolina Oliphant, Lady Nairne (16 August 1766 – 26 October 1845) was a Scottish songwriter. Many of her songs, such as “Will ye no’ come back again?” and “Charlie is my Darling”, remain popular today, almost two hundred years after they were written. She usually set her words to traditional Scottish folk melodies, but sometimes contributed her own music.

Carolina Nairne and her contemporary Robert Burns were influenced by the Jacobite heritage in their establishment of a distinct Scottish identity, through what they both called national song. Perhaps in the belief that her work would not be taken seriously if it were known that she was a woman, Nairne went to considerable lengths to conceal her identity (even from her husband) when submitting her work for publication. Early on she called herself Mrs Bogan of Bogan, but feeling that gave too much away she often attributed her songs to the gender-neutral B.B., S.M.,[a]S.M. stands for ”Scottish Minstrel”. or “Unknown”.

Although both working in the same genre of what might today be called traditional Scottish folksongs, Nairne and Burns display rather different attitudes in their compositions. Nairne tends to focus on an earlier romanticised version of the Scottish way of life, tinged with sadness for what is gone forever, whereas Burns displays an optimism about a better future to come.

Life and antecedents

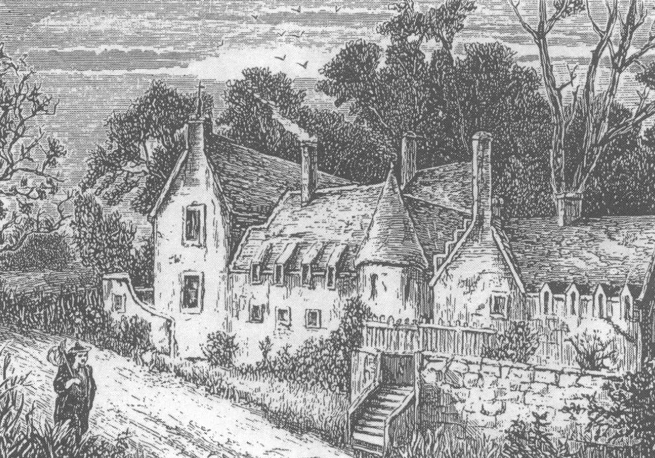

Rogers (1905), The Life and Songs of the Baroness Nairne

Carolina Oliphant was born at the Auld Hoose, Gask, Perthshire (her father’s ancestral family home) on 16 August 1766. She was the fourth child of the three sons and four daughters of Laurence Oliphant (1724–1792), laird of Gask, and his wife Margaret Robertson (1739–1774); her mother was the eldest daughter of Duncan Robertson of Struan, the chief of Clan Donnachie, which fought on the Jacobite side in the uprisings of 1715 and ’45. Her father was also a staunch Jacobite, and she was given the name Carolina in memory of Prince Charles Edward Stuart.[1]

Following the failure of the Jacobite rising of 1745 the Oliphant family – along with the Robertsons and the Nairnes – was accused of high treason, exiled to France, and their estates seized. The exiles remained in France for nineteen years, during which time Carolina’s parents were married at Versailles, in 1755. The government eventually allowed the family’s kinsmen to buy back part of the Gask estate, and the couple returned to Scotland two years before Carolina’s birth.[1][2] Her parents were cousins, both grandchildren of Lord Nairne,[3] who had commanded the second line of the Jacobite army at the Battle of Prestonpans in 1745. Although he was sentenced to death the following year,[4] he managed to escape to France, where he remained in exile until his death in 1770.

The upbringing of Carolina and her siblings reflected their father’s Jacobite allegiance, and their everyday lives were filled with reminders that he considered the Stewarts to be the rightful heirs to the throne. A governess was employed to ensure that the girls did not speak in a broad Scots dialect, as their father considered it unladylike.[5] General tuition was provided by a local minister – the children’s prayer books had the Hanoverian sovereign’s names obscured by those of the Stewarts – and music and dance teachers were also engaged.[1] Delicate as a child, Carolina gradually developed into a genteel young woman, much admired by fashionable families;[6] she was well educated, able to paint, and an accomplished musician familiar with traditional songs.[7]

As a teenager, Carolina was betrothed to William Murray Nairne,[8] another of Lord Nairne’s grandchildren, who became the 5th Lord Nairne in 1824.[1] Born in Ireland to a Jacobite family from Perthshire whose lands had also been forfeited,[7] he regularly visited Gask.[9] It was only after he was promoted to the position of assistant inspector-general at a Scottish barracks that the pair were married on 2 June 1806.[1] The couple settled in Edinburgh, where their only son, also named William Murray Nairne (1808–1837), was born two years later.[10] He was a sickly child and, following her husband’s death in 1830, Lady Nairne lived with her son in Ireland and on the continent.[1][11] The change in climate was not as beneficial to his health as had been hoped; he died in Brussels in December 1837.[12] Nairne returned to Gask in 1843, but following a stroke her health deteriorated; she died on 26 October 1845 and was buried in the family chapel.[7]

Songwriting

| “The Hundred Pipers”, Kenneth McKellar |

| “Will Ye No Come Back Again”, The Corries |

Nairne began writing songs shortly after her father’s death in 1792.[13] She was a contemporary of the best-known Scottish songwriter and poet Robert Burns. Although the two never met, together they forged a national song for Scotland, that in the words of Dianne Dugaw, Professor of English and Folklore at the University of Oregon, “lies somewhere between folk-song and art-song.” For both, Jacobite history was a powerful influence.[14] Nairne could read music and played the harpsichord, which allowed her to contribute some of her own tunes. Three tunes she almost certainly wrote are those to “Will Ye No Come Back Again”, “The Rowan Tree”, and “The Auld House”, as no earlier printed versions have been found.[13]

What was probably her first composition – “The Pleughman” (ploughman) – may have been a tribute to Burns.[13] Just like him, Nairne’s songs were at first circulated by being performed, but her interest in Scottish music and song brought her into contact with Robert Purdie, an Edinburgh publisher. Purdie was gathering together “a collection of the national airs, with words suited for refined circles” to which Nairne contributed a significant number of original songs, all without attribution to her. The collection was published in six volumes as The Scottish Minstrel from 1821 to 1824, with music edited by Robert Archibald Smith.[1]

The bulk of Nairne’s more than eighty songs have Jacobitism as their backdrop, perhaps unsurprising given her family background and upbringing.[1] Examples of the best known of such works include “Wha’ll be King but Charlie?” “Charlie is my darling”, “The Hundred Pipers”, “He’s owre the Hills”, and “Will ye no’ come back again?”. In part she wrote such songs as a tribute to the mid-18th century struggles of her parents and grandparents, but the Jacobite influence in her work runs deep. In “The Laird o’ CockpenSong by the Scottish songwriter Carolina Nairne, Baroness Nairne (1766–1845), which she contributed anonymously to The Scottish Minstrel, a six-volume collection of traditional Scottish songs published from 1821 to 1824. “, for instance, Nairne echoes the Jacobite distaste for the Whiggish displays and manners of the nouveau riche in post-Union Scotland, as does “Caller Herrin’ ”.[13][b]Caller means chilled, frozen.[13]

Most of Nairne’s songs were written before her marriage in 1806. She completed her last – “Would Ye Be Young Again?” – at the age of 75, adding a note in the manuscript that perhaps reveals much of her attitude to life: “The thirst of the dying wretch in the desert is nothing to the pining for voices which have ceased forever!” Indeed, her songs often focus on grief, on what can be no more, and romanticise a traditional way of Scottish life. Her contemporary Burns, on the other hand, had an eye on a global future – “a brotherhood of working people ‘the warld o’er’ that’s ‘comin yet’ ”.[13]

Anonymity

Nairne concealed her achievements as a songwriter throughout her life; they only became public on the posthumous publication of “Lays from Strathearn” (1846).[1] She took pleasure in the popularity of her songs, and she may have been concerned that this could be jeopardised if it became public knowledge that they were written by a woman. It also explains why she soon switched from Mrs Bogan of Bogan to the gender-neutral BB when submitting her contributions to The Scottish Minstrel, and even disguised her handwriting. On one occasion, pressed by her publisher Purdie who wanted to meet his best contributor, she appeared disguised as an elderly gentlewoman from the country. She succeeded in persuading Purdie that she was merely a conduit for the songs she gathered from simple countryfolk, and not their author. But the entire editorial committee of the Minstrel – all of them female – was aware of her identity for instance, as were her sister, nieces and grandniece. On the other hand, she shared her secret with very few men, not even her husband; as she wrote to a friend in the 1820s “I have not told even Nairne lest he blab”.[13]

Consideration for her husband may have been another of Nairne’s motives for maintaining her anonymity. Despite his Jacobite family background he had served with the British Army since his youth, and it might have caused him some professional embarrassment if it had become widely known that his wife was writing songs in honour of the Jacobite rebels of the previous century. Somewhat mitigating against that view however is that she maintained her secrecy for fifteen years after his death.[13]