Eleanor Cobham (c.1400 – 7 July 1452), Duchess of Gloucester and an alleged sorcerer, was in 1441 forcibly divorced from her husband Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, and sentenced to life imprisonment for treasonable necromancy

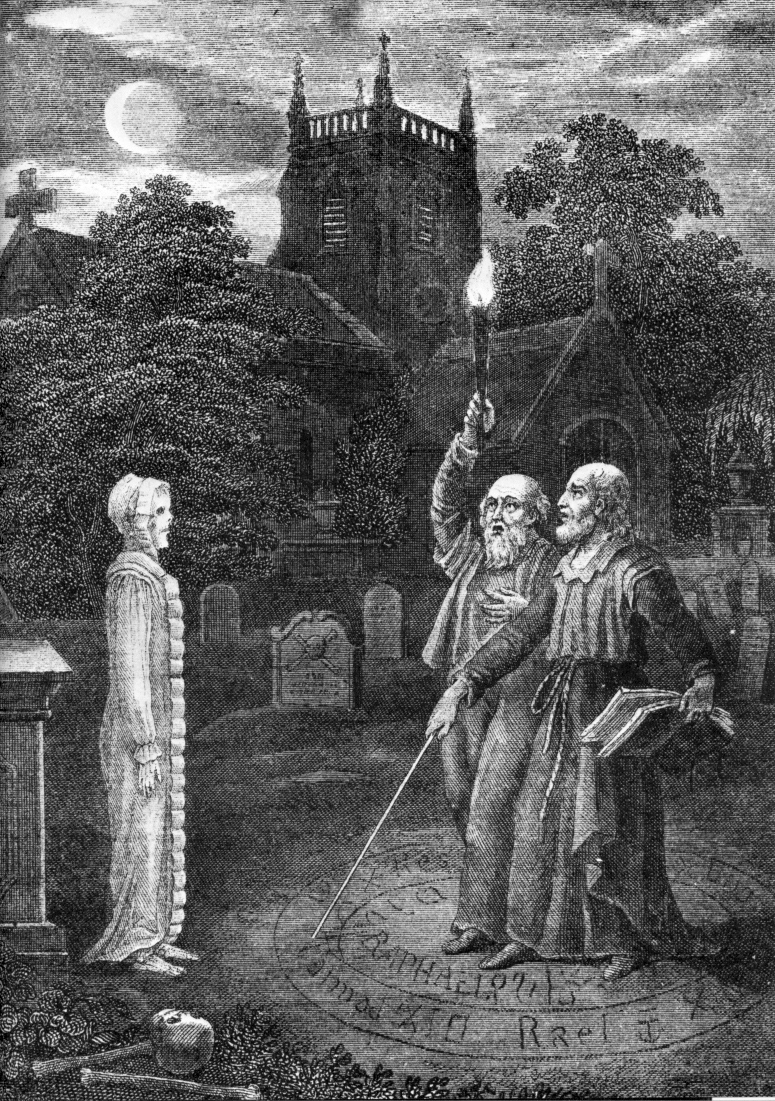

Form of magic in which the dead are re-animated and able to communicate with the sorcerer who invoked them, just as they would if they were alive.

Form of magic in which the dead are re-animated and able to communicate with the sorcerer who invoked them, just as they would if they were alive., consulting astrologers to cast the king’s horoscope.[1][a]It did not become an offence to use astrology or divination to predict the death of the monarch until the 1581 Statute of Silence

Act of Parliament introducing a series of increasingly gruesome punishments for speaking or publishing anything that Queen Elizabeth I did not wish to hear. .

But as in Eleanor’s case, doing so could give rise to the suspicion that those involved might feel encouraged to fulfil the prophecy themselves.

In about 1422 Eleanor became a lady-in-waiting to Jacqueline d’Hainault, who, on divorcing John IV, Duke of Brabant, had fled to England from Hainault – a territorial lordship straddling the present-day border between Belgium and France – in 1421. In 1423 Jacqueline married Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, the youngest son of King Henry IV.[1]

After unsuccessfully invading Hainault to assert his wife’s claims to the territory, Humphrey returned to England in March 1425, and Eleanor became his mistress. When in January 1428 his marriage with Jacqueline was pronounced invalid he married Eleanor.[1]

Downfall

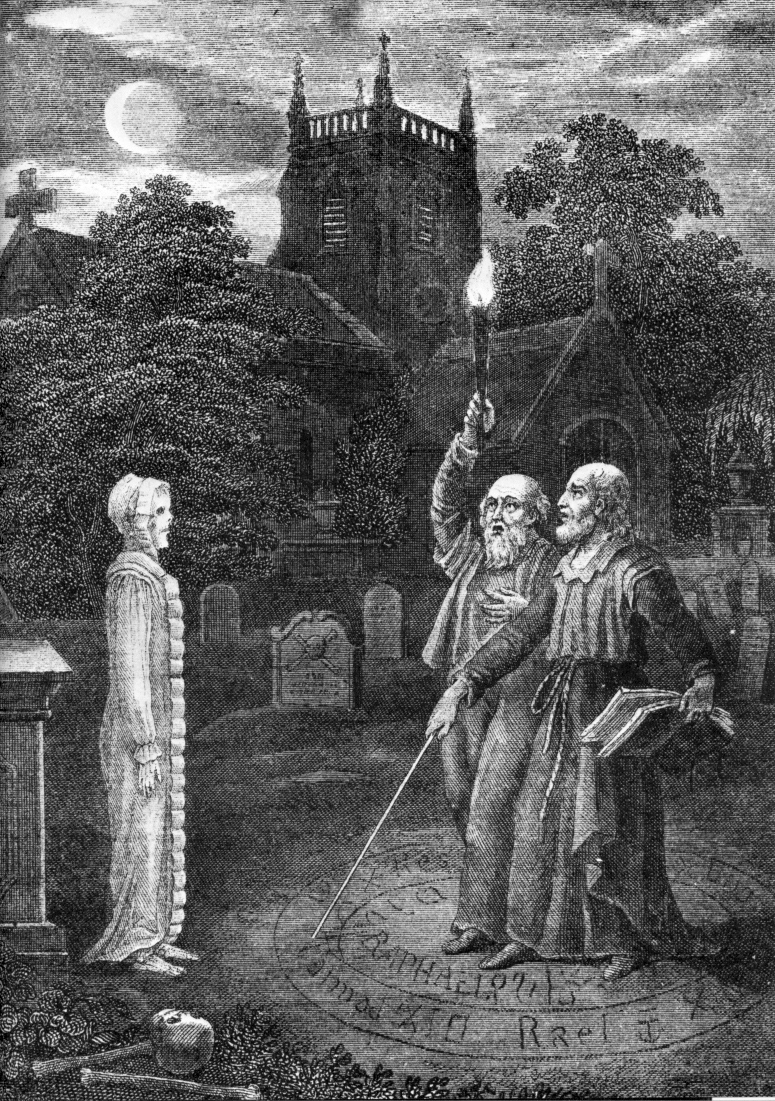

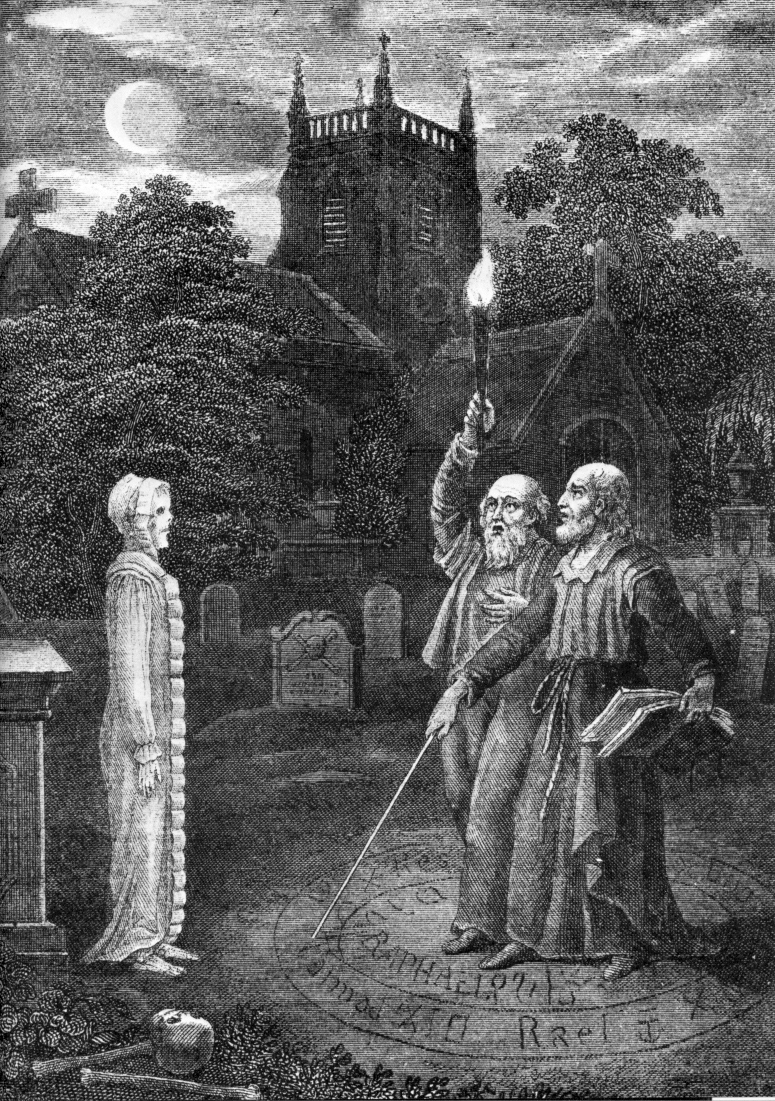

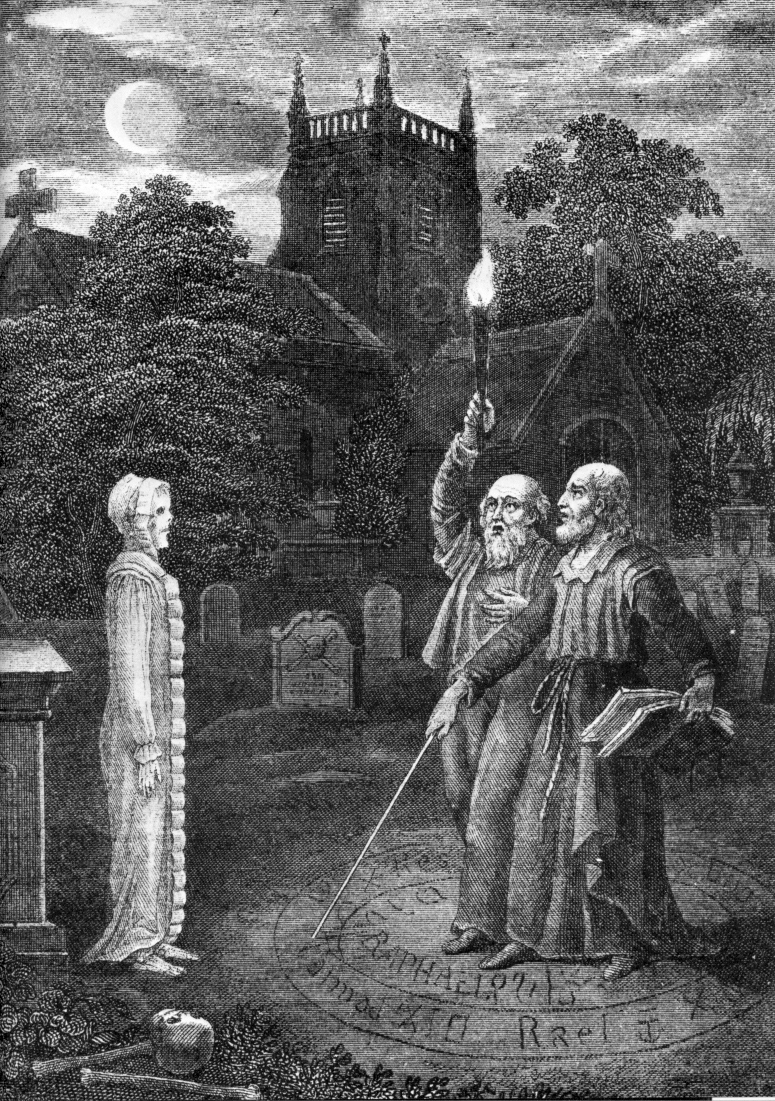

Perhaps having become obsessed with the possibility of her husband succeeding King Henry VI, Eleanor began consulting astrologers to try to divine the future. The astrologers Thomas Southwell and Roger Bolingbroke “unwisely” predicted that Henry VI would suffer a life-threatening illness in July or August 1441. When rumours of the prediction reached the authorities they also consulted astrologers, who could find no such future illness in their predictions and were thus able to reassure the King. Following the rumours to their source, they interrogated Southwell, Bolingbroke and John Home, Eleanor’s personal confessor, and subsequently arrested Southwell and Bolingbroke on suspicion of necromancy

Form of magic in which the dead are re-animated and able to communicate with the sorcerer who invoked them, just as they would if they were alive.

Form of magic in which the dead are re-animated and able to communicate with the sorcerer who invoked them, just as they would if they were alive. and heretical practices in July 1441.[1] Bolingbroke was displayed on a scaffold at St Paul’s Cross in London, wearing a paper crown and surrounded by his instruments of necromancy, and publicly confessed to all that “he doon and wrought by the devyll and his powere”, even though no formal charges had yet been brought against him.[2]

Sanctuary

On hearing news of what had happened to Bolingbroke, Eleanor “wisely” decided to seek sanctuary in Westminster Abbey, which may well have saved her life.[3] Under interrogation by the King’s Council, Bolingbroke claimed that Eleanor had asked him to prophesy whether she would obtain any higher position than that which she currently held. But as the wife of the heir to the throne, the only higher position she could possibly hold would be queen. Southwell, then being held in the Tower of London, was further accused of celebrating a heretical mass to aid Roger in conspiring for the death of the King.[4]

Wikimedia Commons

Eleanor, subject only to ecclesiastical jurisdiction while in sanctuary, was examined by a panel of bishops, and denied most of the charges against her. She did however confess to obtaining potions from Margery Jourdemayne, “the Witch of Eye”, explaining that they were potions to help her conceive.[5][6] It certainly seems to have been the case that Eleanor and Humphrey had a problem with fertility. A note from Humphrey’s physician advises him that “your loins and genitals are being weakened by the unrestrained frequency of your love-making, as the wateriness and scarcity of your semen indicate”, and suggests a change of diet.[7]

Eleanor was found guilty of using witchcraft, and a penance was imposed on her of having to walk hoodless carrying a wax taper to three separate London Churches on three separate days: St Paul’s Cathedral, Christchurch and St Michaels.[b]Witchcraft did not become a crime in England until the 1542 Witchcraft ActSeries of Acts passed by the Parliaments of England and Scotland making witchcraft a secular offence punishable by death., but it was considered by the Church to be heretical. She was also forcibly divorced from Humphrey, possibly because she admitted to having used love magic, suggesting that Humphrey may not have freely consented to the marriage.[8]

Life imprisonment

A King’s Council had already found Bolingbroke, Southwell, Home and Margery Jourdemayne guilty of treason, a case in which Eleanor had been named as an acce[9]ssory. Margery was burnt at Smithfield on 27 October 1441, Bolingbroke was hanged drawn and quarteredStatutory penalty in England from 1352 for men convicted of high treason. on 18 November, and Southwell escaped the same fate by dying “of sorrow” in the Tower of London;[9] the historian Jessica Freeman has speculated that he committed suicide.[10] John Home was pardoned, suggesting that perhaps the allegations had been fabricated.[9]

It was politically unacceptable that Eleanor should simply be turned free and thus be allowed to escape the charges of treason levelled against her so-called accomplices. And so on 19 January 1442 King Henry VI signed a Letter of Warrant condemning Eleanor to a lifetime of imprisonment.[11]

Eleanor was initially confined in Chester Castle, then in 1443 moved to Kenilworth Castle.[1] The move may have been prompted by fears that Eleanor was gaining sympathy among the common people, for just a few months earlier an unnamed Kentish woman had met with Henry VI at Black Heath and scolded him for his treatment of Eleanor, saying he should bring her home to her husband;[12] the woman was punished by execution. In July 1446 Eleanor was moved to the Isle of Man, and finally in March 1449 to Beaumaris Castle in Anglesey, where she died on 7 July 1452.[1]

Notes

| a | It did not become an offence to use astrology or divination to predict the death of the monarch until the 1581 Statute of Silence Act of Parliament introducing a series of increasingly gruesome punishments for speaking or publishing anything that Queen Elizabeth I did not wish to hear. . But as in Eleanor’s case, doing so could give rise to the suspicion that those involved might feel encouraged to fulfil the prophecy themselves. |

|---|---|

| b | Witchcraft did not become a crime in England until the 1542 Witchcraft ActSeries of Acts passed by the Parliaments of England and Scotland making witchcraft a secular offence punishable by death., but it was considered by the Church to be heretical. |