Eliza Armstrong (born 1872) was at the centre of a major scandal in the United Kingdom when in 1885 she was supposedly bought for prostitution to expose the evils of white slavery. She was the daughter of Charles Armstrong, a chimney sweep, and Elizabeth, née Chivers, who were married in March 1874 and lived in Marylebone, London.[1]

While the case achieved its purpose in aiding the passage of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, raising the age of consent for females from 13 to 16,[2] it also had unintended consequences for its chief perpetrator, W. T. Stead, editor of The Pall Mall GazetteEvening newspaper launched in London in 1865, which introduced investigative journalism into British journalism, along with other innovations., who was jailed for his part in the exposé.

£5 virgin

Prostitution was commonplace in London,[a]In his The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon Stead claimed that there were 50,000 prostitutes on the streets of London.[3] and Stead had been persuaded by luminaries including Benjamin Scott, Chamberlain of the City of London and anti-vice campaigner, that among the poor it was routine for mothers to sell their daughters to brothels.[4] To prove his case, he contacted Rebecca Jarrett, a reformed prostitute and brothel-keeper, and engaged her to “buy a girl in the market”, stipulating that she must be 13 years old and a virgin. Rebecca let it be known that she was looking for a servant girl, and of the applicants Eliza Armstrong was the only one of the right age. Eliza’s mother agreed to sell her daughter for £5,[1] equivalent to about £575 as at 2021.[b]Using the retail price index.[5] Rebecca told the mother that her daughter was to serve as a maid to an old gentleman, but was of the opinion that Mrs Armstrong understood she was selling her daughter into prostitution.[6]

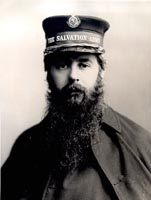

That same day Rebecca took Eliza to the home of Louise Mourez, a French midwife, who examined the girl, attested to her virginity and sold Rebecca a bottle of chloroform to dull the pain of Eliza’s first penetration. The girl was then taken to a brothel and lightly drugged to await the arrival of her purchaser, who was Stead.[7] He entered Eliza’s room and waited for her to wake from her stupor. When she came to the girl screamed, and Stead quickly left the room, letting the scream imply he had “had his way” with her. Eliza was then handed over to Bramwell Booth, the first Chief of Staff of the Salvation Army, who spirited her away to France, first to Paris and then to Loriol-sur-Drome in the south of France.[1]

The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon

On Saturday 4 July 1885, a “frank warning” was issued in the Pall Mall Gazette:

The public’s appetite whetted sufficiently in anticipation, on Monday 6 July, Stead published the first instalment of The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon, the theme of which was child prostitution, and the abduction, procurement and sale of young English virgins to Continental “pleasure palaces”. The instalments were published anonymously by someone signing himself “Chief Director of the Secret Commission”, in reality Stead himself.[9]

In the six-page first instalment Stead argued that while consensual adult behavior was a matter of private morality and not a law enforcement issue, there were five main areas where the law should intervene:[10]

- The sale and purchase and violation of children

- The procuration of virgins

- The entrapping and ruin of women

- The international slave trade in girls

- Atrocities, brutalities, and unnatural crimes.

In his rather “purple prose” style, Stead referred to Eliza as “Lily”, and omitted to disclose that he himself was her purchaser, referring to him only in the third-person.[10][11]

Reaction

The “Maiden Tribute” was an instant hit, despite the refusal of W. H. Smith, who had a monopoly on all news stalls at the main railway stations, to sell the Gazette owing to what they perceived to be its obscene content.[12] But the magazine had anticipated W. H. Smith’s ban and had recruited newsboys to take over distribution in the capital.[13]

Stead’s revelations struck a chord with the public, and the government was soon on the defensive. Those members of parliament who had previously opposed legislative reform began to understand that further opposition would be seen as not only denying the existence of child prostitution, but condoning it. Many of them wanted to have the Gazette prosecuted under obscenity laws, but bowed to the inevitable, and the Criminal Law Amendment Act was passed into law on 14 August 1885.[1]

Unintended consequences

Although Stead was supported in his investigation by the Salvation Army and religious leaders including Cardinal Henry Edward Manning,[14] his plan backfired on him. Rival newspapers investigated the original “Lily” and found that Stead was the “purchaser”. Mrs Armstrong told police that she had not consented to put her daughter into prostitution, saying she understood that she was to enter domestic service. Reluctantly, Bramwell Booth chose to reveal Eliza’s whereabouts in France and she was brought back to London, where she was reunited with her mother on 24 August. Stead, who was on holiday in the Swiss Alps at the time, returned to London and stated that he alone was responsible for Eliza’s disappearance.[1]

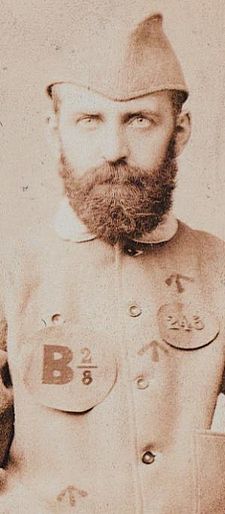

Stead, Jarrett, Booth, Mourez and two others were tried at the Old Bailey in October 1885, charged with the abduction and indecent assault of Eliza Armstrong. The charges against Booth and the Salvation Army were dropped, but Stead, Jarrett, and the others were sentenced to a term of imprisonment;[1] Jarrett and Mourez were sentenced to six months and Stead was sentenced to three, all without hard labour.[15]

Aftermath

The chief prosecutor at the Old Bailey, Harry Bodkin Poland QC, set up a fund to support Eliza and her parents. Some of the money was used to pay for her attendance at the Princess Louise Home in Wanstead, where she was trained for domestic service, but then she vanishes from the historical record. Stead claimed to have received a letter from her saying she was married and had children, but no copy has been found.[1]

The Stead biographer Gavin Weightman has concluded that “just about everything” in Stead’s account of the purchase of Eliza is either “fabricated or inaccurate”, an opinion shared by the playwright George Bernard Shaw, who despite being initially a supporter concluded that Stead’s story of a £5 virgin was “a put up job”.[16] Shaw’s Pygmalion[c]My Fair Lady is the stage and film version. is a parody of Stead’s story;[17] Eliza Armstrong is the model for the flower girl Eliza Doolittle, whose father, a dustman, agrees to sell his daughter to Professor Higgins for £5, as she is of little use to him.[18]

Notes

References

Bibliography

This article may contain text from Wikipedia, released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.