Elizabeth Brownrigg (1720 – 14 September 1767) was an 18th-century English murderer whose victim, Mary Clifford, one of her domestic servants, died from her injuries and associated infected wounds on 9 August 1767 following a series of vicious beatings. Elizabeth was convicted of wilful murder at her trial on 12 September, and was hanged at Tyburn on 14 September 1767.[1]

Public attention was “considerably raised”[2] by the account of Elizabeth’s cruelty towards Mary Clifford and the other children in her care, and she featured in several contemporary pamphlets including An Appeal to Humanity (1767). That her case was still being discussed in later publications such as The Cries of the Afflicted (1795), Brownrigg the Second, or, A Cruel Stepmother (1812), and The Atrocious Life and Horrid Cruelties of Elizabeth Brownrigg (1830), demonstrates her “enduring infamy in the popular imagination”.[1]

Nothing is known of Elizabeth’s parentage or early life. She first appears in the historical record in the late 1740s, when she was working as a servant for a family in London. Then aged about twenty-seven, she married James Brownrigg, a house painter, with whom she moved to Greenwich, and the couple moved to Greenwich. Of their sixteen children, only three boys outlived their mother. In about 1763 the family moved to Fetter Lane, London, where Elizabeth began to practise as a midwife. She was appointed as midwife to the poor in the parish of St Dunstan-in-the-West in 1765, supplemented the family income by taking girl apprentices from the parish workhouse

Establishment where the destitute in England and Wales received board and lodging in return for work. for £5 per child. Her first two charges, Mary Mitchell and Mary Jones, both 14-years-old, arrived at Fetter Lane in 1765.[1]

Torture and abuse

Wikimedia Commons

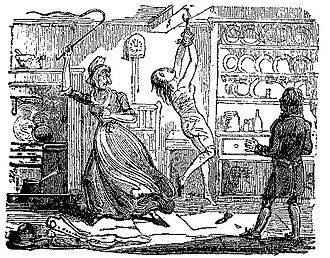

The girls in Elizabeth’s care were subjected to a “punishing regime of work” and regular beatings and confinement. Mary Jones succeeded in escaping to the Foundling Hospital in July 1765, but despite her testimony no action was taken against the family, and a third girl, Mary Clifford, was sent to Fetter Lane in February 1766. Elizabeth, along with her husband and son, continued to torture the children and in particular Mary Clifford,[1] who was regularly stripped and beaten with “divers large whips, canes and sticks” while suspended from a hook in the kitchen.[2] A particularly vicious beating in August 1767 attracted the attention of Elizabeth’s neighbours, and both girls were removed by the parish overseers.[1]

Trial and execution

Elizabeth, her husband James and their son John, were arrested and stood trial at the Old Bailey on 12 September 1767. James and John were acquitted, but Elizabeth was found guilty and was hanged at Tyburn on 14 September.[1] The Murder Act of 1752Act of parliament of England and Wales to increase the horror of being executed for murder by expediting the process and denying the right to a decent burial. mandated that the bodies of hanged criminals were to be denied a decent burial, and instead either dissected by anatomists or publicly hung in gibbets and left to rot.[3] So after her execution Elizabeth’s corpse was taken to the Surgeon’s Hall at the Old Bailey, where her skeleton was put on display following her dissection.[1][4]