Elleine or Ellen Smithe, Smith or Smythe, was an English woman from Maldon, Essex, convicted and hanged for witchcraft in 1579. The evidence against her, together with that of Elizabeth FrancisEnglish woman tried three times for witchcraft, hanged in 1579 for bewitchment and murder by witchcraft. and two other accused women, was included in a pamphlet published shortly after their trials, “A Detection of Damnable DriftesSixteenth-century pamphlet describing prominent Chelmsford witchcraft trials against Elizabeth Francis and othersSixteenth-century pamphlet describing prominent Chelmsford witchcraft trials against Elizabeth Francis and others“.

The evidence cited in the pamphlet details a dispute between the impoverished Elleine and her step-father over money she had received from her mother, who had been found guilty of witchcraft five years earlier. A neighbour’s young child died soon after being harshly reprimanded and injured by Elliene for fighting with her daughter. Various familiarsDemonic spirit who attends upon a witch, possessing magical powers that can be used for good or evil. Often taking the form of a small animal such as a cat. are described, and Elleine’s own teenage son provides details of three spirits.

Background

Elleine Smithe, also given as Ellen Smith or Smythe,[a]In Scotland and England during the sixteenth century spelling was haphazard, leading to many words, places and names having several variations. Modern-day texts often use an anglicised version.[1] lived in Maldon, Essex. She had at least two children: a thirteen-year-old-son and a daughter. Her mother was Alice Chandler or Chaundeler, who was hanged in 1574 after being convicted of killing three people – an eight-year-old child, a thirty-year-old weaver and his five-year-old daughter[2] – by witchcraft.[3][4]

Tainted by her mother’s poor reputation and of low character, Elleine’s impoverished circumstances meant she often resorted to begging or had to rely on poor relief.[5]

Evidence

The evidence against Elleine is detailed in “A Detection of Damnable DriftesSixteenth-century pamphlet describing prominent Chelmsford witchcraft trials against Elizabeth Francis and othersSixteenth-century pamphlet describing prominent Chelmsford witchcraft trials against Elizabeth Francis and others“, a pamphlet produced in the days following her conviction and execution, although it is likely to be an amended and paraphrased version by the pamphleteer. Despite omitting the date of the assize,[b]The academic Marion Gibson suggests the date was not given because “the pamphleteer does not even know the assize date”, but qualifies this by adding “although he presumably attended”.[6] he may have composed the text from shorthand notes he took as the statements were given or read out in court.[7]

According to the pamphleteer, before she was executed Elleine’s mother had given her daughter some money, which after her death Elleine’s step-father, John Chaundeler, insisted must be returned to him. The pair argued vociferously over it and she told him he would regret the altercation. Less than an hour later John became fatally ill, unable to digest any food as everything was vomited back up. Before he died, he claimed his illness was caused by Elliene bewitching him.[3][8]

The next item describes incidents involving Elleine’s son and a neighbour, John Estwood; the boy went begging to Estwood’s house but was chased away empty handed. The child returned home and, as he was relaying the story to his mother, Estwood was suddenly gripped with pain. The next evening as Estwood was sitting at his fireside chatting with a friend, they thought they glimpsed a rat running up the flue; shortly afterwards the creature fell down, but had transformed into a toad. Catching the animal using a set of tongs, the men pushed it into the flames, which turned bright blue before being almost extinguished. Reflecting the commonly held belief that when a witch’s familiarDemonic spirit who attends upon a witch, possessing magical powers that can be used for good or evil. Often taking the form of a small animal such as a cat. is harmed she will feel severe discomfort and appear wherever the event is taking place, Elleine was consumed with pain then arrived at Estwood’s house under the false pretence of enquiring after his health.[9]

Two other pieces of evidence are given in the pamphlet. The first relates a tale of an argument between Elliene’s daughter and four-year-old Susan Webbe; an outraged Elliene struck out at Susan when she saw her the following day, hitting the youngster on the face. The child went home but was immediately taken ill, constantly screaming to her widowed mother for the witch to be taken away. Susan died the next day. A day later her bereaved mother claimed she saw a creature resembling a black dog leaving her house.[9] The indictment against Elliene indicates Susan died on 8 March.[10]

The final item recounted as evidence in the pamphlet also involves familiars and was given by the son of the accused. He revealed his mother had three spirits – Great Dick, Little Dick and Willet – that were housed in a wicker bottle, a leather bottle and a wool cannister. Although the containers were found when the house was searched, the familiars were not.[9]

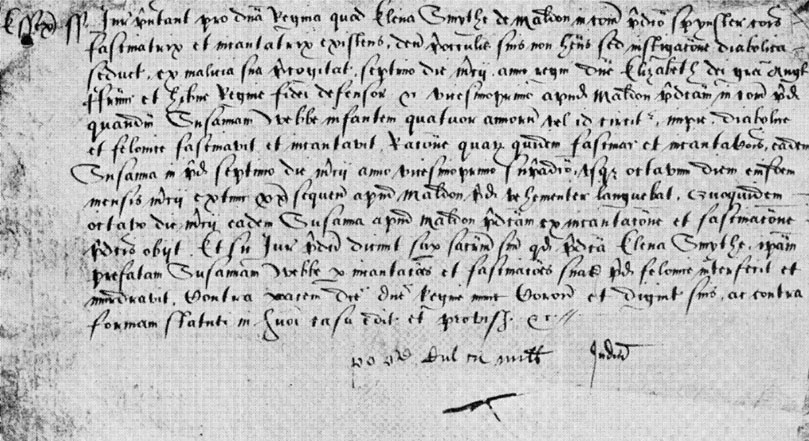

Indictment and verdict

The original indictment against Elliene has survived.[3] It shows the only charge levelled against her was concerning the death of Susan Webbe.[11] She confessed to the crime of bewitching the child to death, was convicted and hanged.[3][12]

Notes

| a | In Scotland and England during the sixteenth century spelling was haphazard, leading to many words, places and names having several variations. Modern-day texts often use an anglicised version.[1] |

|---|---|

| b | The academic Marion Gibson suggests the date was not given because “the pamphleteer does not even know the assize date”, but qualifies this by adding “although he presumably attended”.[6] |