The Forest of Dean Coalfield in west Gloucestershire is one of the smaller coalfields in the British Isles. For hundreds of years, mining in the Forest of Dean Coalfield has been regulated through a system of freemining in which qualifying individuals are granted leases to mine specified areas known as gales.

The Coal Industry Nationalisation Act 1946 exempted the Forest of Dean because of its unique form of ownership and history. The last of the big gales closed in 1965, and today only a handful of small collieries are operating.

Geography and geology

The Forest of Dean in west Gloucestershire covers the hilly area between Coleford to the west, Newnham in the east, Mitcheldean in the north and Bream to the south. The coalfield lies between the River Severn and the River Wye. The coal measures outcrop in three roughly concentric circles close to the edge of the Forest. Most coal seams are thin but 14 have been worked. Iron ore has been mined in the sandstone and the limestone formations beneath and around the coalfield. Ochres and iron oxides are also mined for use as colouring agents.[1] The coal measures occupy about 16,700 acres (6,758 ha), overlying beds of Millstone Grits.[2]

The coalfield, a raised basin plateau of Paleozoic rocks that were folded in the Variscan Orogeny,[a]The Variscan Orogeny was a mountain-building event. was formed during the Upper Carboniferous period, when the area was an intertidal environment of estuaries and swamps. The coalfield occurs in a raised asymmetrical syncline,[b]A syncline is a fold or depression. with a steeper eastern limb; its edges are almost entirely exposed at the surface.[1]

Mining is hampered by underground water trapped in the basin-shaped strata. Water penetrates where valleys cut through exposed limestone and sandstone at the edge of the basin and via underground via swallow holes, cracks, fissures. and through geological faults.[3] Faulting or folding is largely absent in the coal seams which have a regular outcrop. FiredampDamps is a collective name given to all gases other than air found in coal mines in Great Britain. The chief pollutants are carbon dioxide and methane, known as blackdamp and firedamp respectively. is almost entirely absent in the coal seams, and naked lights were in frequent use into the 20th century.[2]

History

Coal mining took place in the forest before Roman times. Small mines were widespread but iron mining originally was of greater importance and coal was a by-product. In medieval times the forest’s miners were valued as sappers and conscripted for military service. Many served in Scotland under Edward II and Edward III. In return for their service particularly in the sieges of Berwick, the Crown granted them privileges in a code of customary mining law.[4] Mining was administered by the Mine Law Court which sat at the Speech House from 1682 after years of meeting in the open. The earliest extant copy of Dean Miners’ Laws and Privileges, the Book of Dennis, dates from 1610 and contains references to earlier origins.[3] The court settled disputes and preserved the system of mining established in the Middle Ages by levying fines for breaches of custom that were paid in coal, ore or cash.[4]

When Edward Terringham, a Gentleman of the Bedchamber in the court of Charles I was granted a monopoly to mine coa, infringing the rights of freeminers, it led to widespread violent confrontations. Terringham built a drainage sough and brought in workers from Staffordshire. About 25,000 tons of coal was shipped via the River Wye in 1680.[5]

In 1787 there were 121 small coal mines or gales in the forest: 90 were working and 1,816 tons of coal were produced weekly by 662 free miners. The following year, 106 collieries were recorded, mostly around Parkend and Ruardean. They were worked by 442 miners, many of them boys and six were women. In the 1770s and 1780s, coal was sent to many parts of Gloucestershire, to Hereford, Monmouth, Chepstow, and Bristol but high transport costs and the development of the Newent coalfield in the 1790s caused a loss of markets.[4]

The coalfield’s output in 1841 was 145,136 tons, but after a slump in the early 1860s had increased to 837,893 tons in 1871. The big producers in 1856 were Parkend with 86,873 tons, Lightmoor with 86,508 tons and Crump Meadow produced 41,507 tons. Drifts and shallow pits working the outcrop produced less than 5,000 tons for local use.[4]

In 1870 almost three quarters of the coalfield’s output, some of which was used locally but most for markets outside the forest, was produced at the Resolution and Safeguard, Lightmoor, Foxes Bridge, Crump Meadow, Trafalgar, and New Fancy Collieries, all of which produced more than 50,000 tons.[4]

In 189, when the main collieries were near Cinderford or Parkend working the upper measures for household and other coal, 1,176,712 tons were raised. Other large mines such as the Princess Royal Colliery Company’s Flour Mill and Park Gutter tapped the lower measures near the outcrop to produce coal for gasworks and steam coal. Richard Thomas & Co worked a large colliery at Lydbrook.[4]

Accessing the deep lower measures in the centre of the forest was hampered by opposition from the free miners. The gaveller, using powers acquired in 1904, created seven large holdings.[6] He amalgamated many gales that were then held by several hundred free miners who, acting through committees, leased them to a company that paid a royalty for each ton of coal raised, to be shared annually at the Speech House. Four collieries were started under the system. Cannop began production in 1909. Henry Crawshay & Co started Eastern United at Staple Edge near Ruspidge in 1909. The Lydney and Crump Meadow Collieries reopened Arthur and Edward as the Waterloo Colliery. Princess Royal Colliery incorporated Flour Mill into its workings and after 1914 centred its production at a new shaft at Park Gutter.[4] Output declined after World War II.[6]

Wikimedia Commons

Coal production fell during the economic recession of the early 1930s but rose to 1,439,000 tons in 1936 after which it declined. Older deep mines closed once they had worked out accessible reserves. Trafalgar closed in 1925, Crump Meadow in 1929, and Foxes Bridge in 1930. Employment fell from 7,818 in 1920 to 5,276 in 1930. Lightmoor employed 600 workers in 1934. Northern United started by Henry Crawshay began sinking in 1933. In the south of the coalfield, Princess Royal worked worked Norchard Colliery from 1937. Lightmoor and New Fancy collieries closed in 1940 and 1944. Many small collieries had fewer than 40 employees. Coal mining employed 55 per cent of the adult male population, 84.5 per cent round Cinderford.[4]

After nationalisation in 1947 the National Coal BoardStatutory corporation created to run the coal mining industry in the United Kingdom under the Coal Industry Nationalisation Act 1946. took over the large collieries and licensed smaller gales. Annual production was 777,000 tons in 1948, but declined as costs rose. Eastern United and Waterloo closed in 1959, Cannop in 1960, Princess Royal in 1962, and Norchard Drift and Northern United in 1965, ending deep mining. After 1965 coal was extracted on a small scale, under licence from the National Coal Board (later British Coal) and the Forestry Commission, and by opencasting and the land returned to forestry.[4]

Collieries

The collieries or gales, most of which were small, were given imaginative and unusual names, such as ”Strip and At It”, ”Gentleman Colliers” or ”Rain Proof”. Coal was extracted from seams or delfs named Rocky, Lowery, and Starkey. Child labour was used extensively underground to drag loads of coal until 1842 when it was made illegal.[6]

- Arthur and Edward near Lydbrook was also known as Waterloo. (NCB) The pit had a Cornish pumping engine until the early 1860s. In 1949 the pit was flooded by an inrush of water from the old East Slade Pit but one miner knew a way out through old workings and led his four colleagues to safety at Pludds Colliery.[7] Waterloo survived nationalisation but closed in 1959.[4]

- Bilson was bought by Edward Protheroe M.P. for Bristol in 1826. It employed 700 hands in 1841, 40 were aged under 13.[4] produced 4,482 tons of coal in 1880.[8]

- Cannop (NCB) near the bottom of Wimberry Slade worked the lower coal measures in the centre of the Forest. It began production in 1909.[4]

- Crump Meadow was sunk in 1824 and Edward Protheroe M.P. for Bristol developed the colliery in 1829.[4] The colliery produced 75,173 tons of coal in 1880.[8] It had a Cornish engine house for pumping water and another for winding. It had a 105-year life spanand production ceased in 1929.[9]

- Eastern United (NCB) a drift mine, was started by Henry Crawshay & Co at Staple Edge near Ruspidge in 1909.[4]

- East Slade close to Ruardean Woodside closed in 1910.[10]

- Flour Mill in the Oakwood valley near Bream tapped the lower coal measures, including the Coleford High Delf seam, near its outcrop on the south of the coalfield. The colliery produced coal for gasworks and steam engines. It was worked by the Princess Royal Colliery Co.[4]

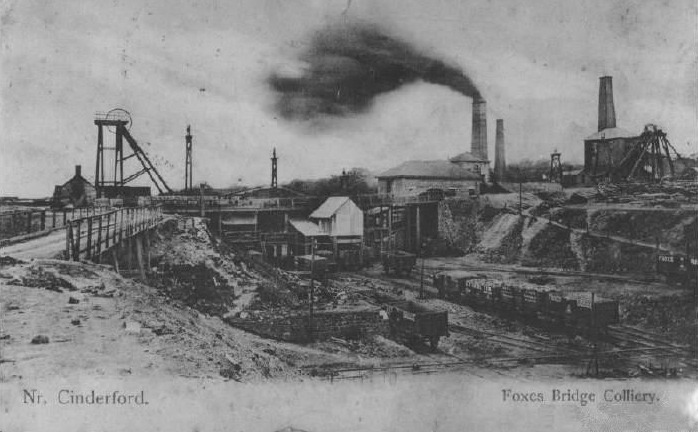

- Foxes Bridge at Crabtree Hill produced 126,978 tons of coal in 1880.[8] It was operated by Henry Crawshay and Company and closed in 1930[11] because of flooding from disused mines.[4]

- Lightmoor had four shafts in the mid-1850s. The colliery produced 60 tons of coal in 1880.[8] It belonged to Henry Crayshaw and Company and had lasted for a century when it closed in 1940. Its shaft which eventually reached the Brazilly seam at 936 feet (285 m) intersected 18 coal seams, not all of which were workable.[12] Lightmoor had a workforce of 600 in 1934.[4]

- New Fancy was developed by Edward Protheroe M.P. for Bristol in 1831.[4] The colliery produced 8,382 tons of coal in 1880.[8] It worked the Coleford High Delf seam and closed in 1944.[13]

- Norchard (NCB) was worked by the Princess Royal Colliery Co from a new drift near Pillowell from 1937.[4]

- Northern United (NCB) originally owned by Henry Crawshay and Company began sinking in 1933 north-west of Cinderford by the Mitcheldean-Coleford road.[4] It accessed the Coleford High Delf seam at a depth of 700 feet (213 m). It closed in 1965.[14]

- Parkend was aquired by Edward Protheroe M.P. for Bristol from his uncle John Protheroe in 1812. The colliery produced 86,873 tons of coal in 1871.[4]

- Princess Royal (NCB) produced 2,665 tons of coal in 1880.[8] It worked Norchard Colliery from a new drift near Pillowell from 1937.[4]

- Speculation produced 18,694 tons of coal in 1880.[8]

- Strip And At It was a deep mine worked from a shaft sunk in the mid 1830s on Serridge Green by John Harris, a free miner. It was taken over by the nearby Trafalgar Colliery.[4]

- Trafalgar near Cinderford, developed by the Brain family, was in production in 1860. It was the only large mine run by free miners in the late 19th century.[4] Trafalgar produced 88,794 tons of coal in 1880.[8] In 1882 it was the first colliery in England to have electric pumps. It took over the workings of the adjacent Strip And At It, to which it was connected by a short underground tramroad. Flooding halted production in 1919, and it closed in 1925.[4]