Flagmakers

George Tutill (1817–1887), artist and entrepreneur, was born in Howden in the East Riding of Yorkshire. The business he started when he was twenty-years-old manufactured banners and regalia for unions, friendly societies, masons throughout Britain and the world. Its factory in the East End of London survived until the London Blitz in 1940.

Tutill led an unconventional life in London; his daughter, conceived out of wedlock, inherited the company which continued until 1967. Tutill moved to the Red House in Upton Lane, West Ham before 1871 and remained there until his death in 1887.

His company produced about three-quarters of all union banners, even though his factory was a non-union shop. Many examples of the company’s work survive, and some have been preserved by the People’s History Museum in Manchester.

Family life

George Tutill was the son of corn miller, Thomas Tutill and his wife Elizabeth Richardson who is reputed to have been a regalia apron maker. He was baptised in Howden on 19 April 1817, three days after his birth. Few details of his early life survive but his family appears to have moved to Hunslet near Leeds before 1823. There is no evidence to support a story that Tutill started as a travelling showman but he claimed to have started his business as a banner maker by 1837. On 28 June 1838 he married Emma Fairfield in Sculcoates, Yorkshire, giving his occupation as artist, and in 1841 he was living in John Street, Tower Hamlets, London with his wife, who died from tuberculosis later that year.[1]

Tutill led an unconventional domestic life following the death of his wife. He entered into a relationship with Elizabeth Bale, a mother of four children whose husband kept an eating-house in Leadenhall Street. Elizabeth gave birth to Georgina Tutill Bale in 1855 and a son, George, in 1862, who died in 1864. Tutill moved to the Red House, in Upton Lane, West Ham before 1871, and lived there with his “wife”, Elizabeth, their daughter, and three servants. He eventually married Elizabeth in April 1878 after she had been widowed, and shortly before their daughter married Charles Henry Lewis. Tutill visited Australia, New Zealand, and the United States in 1881.[1]

Career

Tutill, the artist, exhibited landscape paintings, among them Scarborough Castle at the Royal Academy in London in 1846, and five works including Douglas Bay (1850), Holy Island Castle (1851), and Glengareff (1852) at the British Institution.[1]

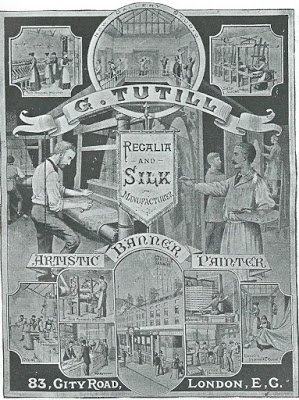

Tutill made his name and fortune, not as an artist but as an entrepreneur, manufacturing banners and regalia. By 1851 he was “banner supplyer”, and before 1860 his business occupied a factory at 83, City Road in East London.[1] It was close to cheap, skilled labour descended from the Huguenot silkweavers who settled in Spitalfields and Bethnal Green.[2] Tutill installed hand looms in the factory to control the quality of the silk, produce the designs of his choice and control production. He patented a treatment for coating silk fabric with a rubber solution and linseed oil for making flags and banners in July 1861.[1]

Banners

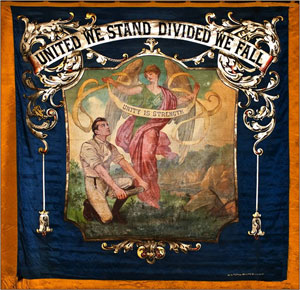

Tutill’s made double-sided banners of woven silk painted in oils on both sides. Brightly coloured silk backgrounds were embellished with golden scrolls, ornate lettering and the central painted image was often surrounded by inset cameos. The company wove raw silk to the required size using a Jacquard loom that Tutill claimed was the world’s largest in the 1880s. He employed artists and signwriters for different aspects of the banners. Not universally appreciated, the banners attracted criticism for their “ostentatious gaudiness” and “uninspired academicism of the central images”.[1] His work was not restricted to the British Isles and the company completed orders for unions and friendly societies in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa He visited Australia, New Zealand, and the United States in 1881. Victorian civic and community associations, friendly societies, trade unions, freemasons and Sunday schools all used Tutill’s for their emblems, regalia, and banners..[1]

Tutill’s stranglehold on banner production and designs for miners’ banners changed little showing the their identification with past struggles and desire for change.[3] Banners mapped the social and ideological development of working-class politics. The early 19th-century banners drew on classical and biblical themes emphasing the respectability of labour, but from the late 1880s the new unions chose more overtly political and socialist images and slogans. Tutill’s house style dominated and was widely imitated.[1]

Legacy

Tutill died in February 1887 at Red House. He was buried at Howden Minster where a stained-glass memorial window was installed in 1888. The business passed to his daughter and was managed by her second husband, and then her son. Tuthills prospered during the 1890s but demand declined until after the First World War; after the 1926 General Strike demand again declined until 1947, when the company again prospered. In 1967 Tutill’s did not make a single trade union banner for the first time for 130 years.

Few examples of George Tutill’s own work survive, but there are more examples from the company after his death. His extensive business and photographic records were destroyed in the London Blitz. Tutill made his fortune from the unions while running a non-union shop that produced three quarters of union banners. Examples of Tuthill’s work can be found in the People’s History Museum in Manchester.[4]