Wikimedia Commons

Gertrude Vernon, Lady Agnew, was a socialite who gained significant prestige and notoriety from her portrait Gertrude Vernon, Lady Agnew of Lochnaw (1864–1932)Oil on canvas portrait of Lady Agnew by John Singer Sargent completed during 1892. Commissioned by her husband Sir Andrew Noel Agnew, 9th Baronet., previously named Lady Agnew of Lochnaw, by the Florence-born artist John Singer Sargent.

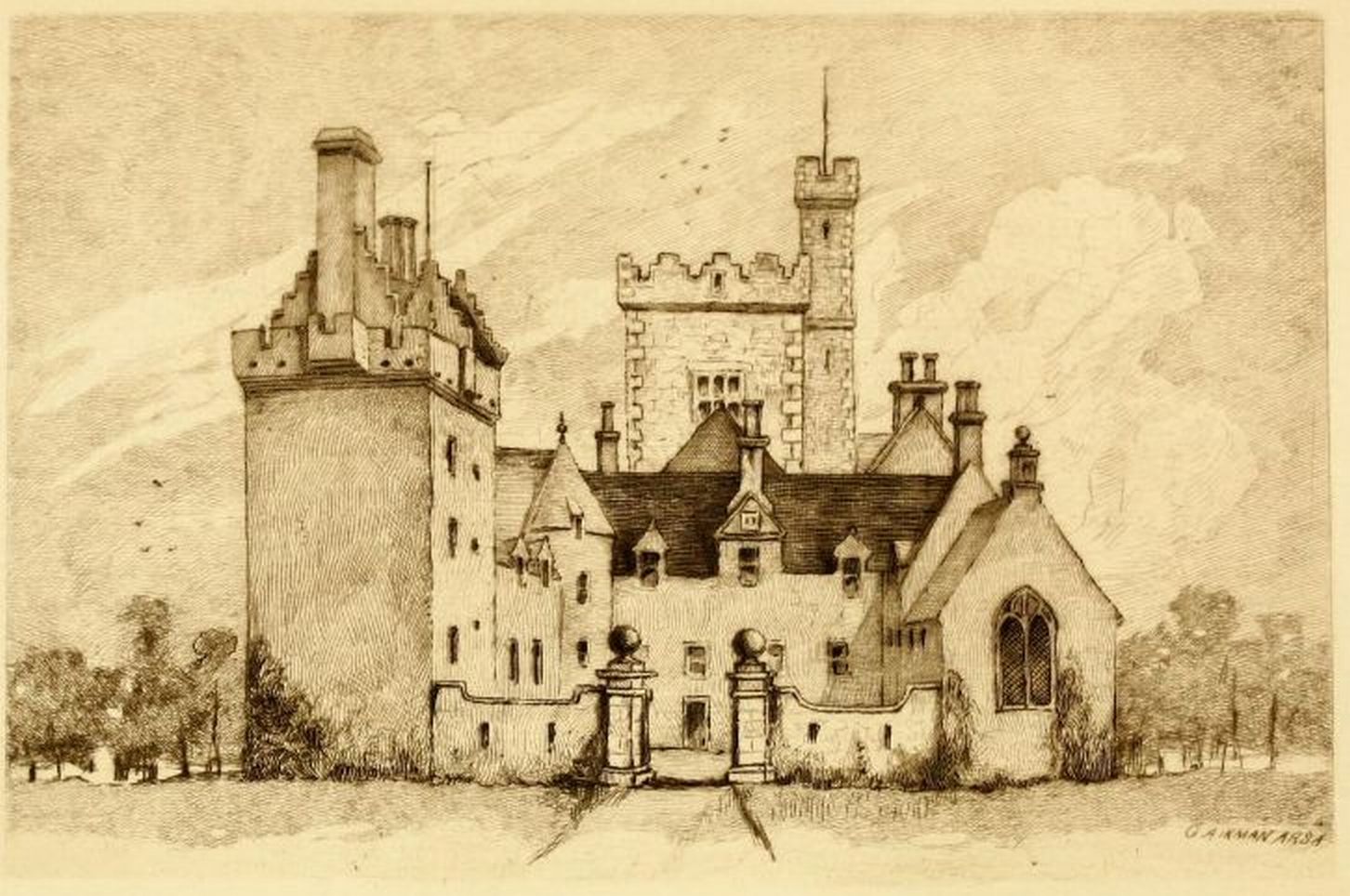

Gertrude married Andrew Noel AgnewDescendent of an old Scottish family whose main seat was Lochnaw Castle in Wigtownshire, Scotland. Descendent of an old Scottish family whose main seat was Lochnaw Castle in Wigtownshire, Scotland. , who was descended from an old Scottish family, on 15 October 1889, despite making it clear that she had no deep feelings for him. Lady Agnew seems to have suffered from persistent health problems throughout her marriage, which may explain her somewhat languorous appearance in her portrait.

There is some speculation that the family may have met with financial difficulties, resulting in the sale of Lady Agnew’s portrait to the National Gallery of Scotland in 1925. She died in 1932 following a prolonged period of ill health.

Early life and antecedents

Gertrude Vernon was born on 15 May 1864;[1][2][a]Anomalies appear concerning Lady Agnew’s date and year of birth: Cokayne gives 16 June 1860 but indicates she was the youngest daughter of Vernon;[3] a birth notice in the Morning Chronicle indicates her mother gave birth to a daughter on that date but does not specify any further detail;[4] on its website the National Galleries of Scotland gives 1864[5][6] and Christopher Baker, former Director of European and Scottish Art and Portraiture at the National Galleries of Scotland – now Editor of The Burlington MagazineMonthly publication covering the fine and decorative arts of all periods, founded in 1903.,[7] also gives 1864 whereas Sir John Leighton, Director-General of the National Galleries of Scotland, simply states she was fifteen years younger than her husband;[8] and historian Julia Rayer Rolfe has 15 May 1865.[2] although little information is available about her early life, her aristocratic ancestors provide an indication of her background.[9] Gertrude was the youngest daughter of the Hon. Gowran Charles Vernon (1825–1872) and his wife Caroline Fazakerly (1828–1884); the couple had two other daughters, Eleanor Emma Albreda (1858–1949) and Dorothy Harriet (1861–1914) plus a son, Robert Brian Gowran (1867–1869), who died before reaching maturity.[10]

Gertrude’s father, a Midland circuit barrister who was appointed as Recorder of Lincoln in 1859,[11] was the son of Robert Vernon, first Baron Lyveden (1800–1873) and his wife, Emma Mary Wilson (1808–1882). Lady Lyveden was the natural daughter of John FitzPatrick, second Earl of Upper Ossory (1745–1818); despite being a minor – she was 14 or 15 years old when they married on 15 July 1823[b]Rolfe quotes Lady Lyveden’s year of birth as 1808.[12] Until the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 the legal age of consent for females was 13.[13] – she brought significant assets to the marriage.[14] Baron Lyveden was born Robert Vernon Smith but changed his name to Vernon by royal licence in 1859; his children had already been assumed the surname, again by royal licence, in 1846.[15] A prominent politician, he held several ministerial positions and served on the Lunacy Board of Commissioners.[16] His father, Robert Percy Smith (1770–1845), or Bobus Smith as he was known, made an immense fortune in India before returning to England and taking up a career in politics.[17]

Lady Agnew’s mother also came from a family of politicians; Caroline’s father was John Nicholas Fazakerly (1787–1852), member of Parliament for Peterborough,[18] who had married Hon. Eleanor Montagu, daughter of Matthew Montagu, 4th Baron Rokeby. The Fazakerly family had, like the Vernons, undergone a change of name. Caroline’s grandfather, John Fazakerly, had previously been John Radcliffe of Prescot, Lancashire; the change was made after his father, Thomas Radcliffe of Ormskirk, inherited the fortune of Nicholas Fazakerley (1682–1767), the member of parliament for Preston, after pursuing an action in the Chancery court.[c]Thomas Radcliffe was a second cousin once removed of Nicholas Fazakerley.[19] The Radcliffes were an old Lancashire family who, after receiving the inheritance, “led a gentlemanly existence”.[19]

By the time Gertrude was in her late teens both her parents had died, so she lived with her older sister Dorothy in London’s Eaton Square.[9] Lady Lyveden, Gertrude’s grandmother, died in 1882, leaving a generous bequest to her granddaughter, sufficient that she was able to maintain an independent lifestyle.[20]

Marriage

Wikimedia Commons

In May 1888 Gertrude met Andrew Noel AgnewDescendent of an old Scottish family whose main seat was Lochnaw Castle in Wigtownshire, Scotland. Descendent of an old Scottish family whose main seat was Lochnaw Castle in Wigtownshire, Scotland. ,[20] a barrister who had been called to the bar in 1874.[21] A descendent of an old Scottish family, his parents were Sir Andrew Agnew, 8th baronet of Lochnaw and Lady Louisa,[d]According to the details in the Complete Baronetage, her name was Mary Arabella Louisa.[3] the daughter of the first Earl of Gainsborough.[22] The Agnew’s main residence was Lochnaw Castle in Wigtownshire, which had been the family seat for about six hundred years.[23]

Two months later, in July, Agnew arrived in Pitlochry where Gertrude was visiting with a friend, Miss Balfour. His first proposal of marriage occurred after spending four days joining the pair on their excursions; Gertrude refused but, undeterred, Agnew continued to pursue her for a year, intermittently repeating his proposal which was rejected. Eventually, Gertrude capitulated and the couple were engaged on 15 June 1889, but she made no pretence that she had any deep-seated feelings for Agnew.[20]

Despite the Agnew family’s misgivings – they felt Agnew was just infatuated with Gertrude and did not consider it a good match – the couple married on 15 October 1889. The ceremony took place in St Peter’s Church, Eaton Square, London with the reception at 4 Belgrave Place, the town residence of Gertrude’s uncle, Lord Lyveden, who had given the bride away. The newly-weds then called at Lord Lyveden’s country seat of Farming Woods, Northampton before proceeding on to Lytham Hall in Lancashire, the home of Agnew’s sister. Lochnaw Castle was the couple’s ultimate destination for their honeymoon.[20]

Married life

Life for the Agnews consisted of summer seasons spent entertaining in London; lavish dinner parties were attended and hosted.[23] Garden parties were staged at Lochnaw Castle; some were grand gatherings with pipe bands, others were entertaining friends or family. Once Agnew gained his inheritance the couple’s social activities expanded further.[24] Lady Agnew gained a reputation for the magnificent dinner parties she hosted with the progression of entertainments escalating in tandem with the increasing size of the town houses the couple rented.[25] Her extensive skills in the appropriate decorating, furnishing and restoring of houses were used to advantage.[26]

During 1892, Agnew commissioned John Singer Sargent to paint her portraitRedirected to Gertrude Vernon, Lady of Lochnaw (1864–1932)..[5] The success of the painting endowed her with additional notability and prestige[27] as well as launching the artist’s British career on to an upward trajectory.[8] He painted many members of the high society who populated the Agnews extensive dinner party guest lists. Apart from the couple’s own aristocratic relatives, others given hospitality included Arthur Balfour, the British Prime Minister, John Pierpoint Morgan, the American banker and financier,[28][e]Morgan was visiting London to view his art collection at an exhibition in what is now the Victoria and Albert Museum, Kensington.[25] and, in 1914, musical entertainment at one of the Agnew soirées was provided by Percy Grainger.[29]

As the years of married life progressed, Lady Agnew seldom visited Lochnaw Castle except for an occasional summer visit. She spent time in country houses close to London during the autumn months including the property she owned at Whitehill Farm in Hertfordshire and Woodcock Lodge near Hertford. From 1904, when they relinquished their London house at 16 Eaton Square, the couple spent little time together as her husband predominantly stayed at his country seat in Lochnaw. Their joint high society lifestyle however resumed when they moved into a town house at 10 Smith Square in the city. Sumptuous dinners and dances were hosted there in the years prior to the First World war.[30]

When Lady Agnew’s older sister, Dorothy, died in 1914, she inherited her house, which was next door at number 11; both houses were soon after commandeered by the Admiralty for war use on the outbreak of hostilities. During the war years her husband was mostly in Edinburgh while Lady Agnew took up residence on the farm at Whitehill, where she owned a number of agricultural properties; her lifestyle became that of a hobby farmer producing barley and other crops. She still entertained, hosting weekend breaks for friends to assist with farm tasks like haymaking.[30]

Malaise

Lady Agnew had persistent health problems; a few days after the couple returned to London from their honeymoon, Agnew recorded in his diary that “G was very unwell and tired.”[23] He had also sought medical advice shortly after their engagement as she had been incapacitated.[23]

Less than six months after their marriage Lady Agnew contracted influenza; residual effects of the illness continued through all of 1892 despite periods of convalescence. She spent six weeks recuperating in Pitlochry from July 1890 having been taken there by ambulance carriage. Her general malaise appeared to diminish in February 1891 but a trip up to Lochnaw at the end of March again resulted in her feeling ill and light-headed.[23]

Although Singer Sargent completed Lady Agnew’s portrait in six sittings, the sessions were disrupted by her incapacity. She was attended by her doctor after the second sitting was completed on 18 June 1892, as she was unwell and required time to recuperate in bed.[31] Her illness may account for the languorous pose in her portrait.[32]

Over the years several unsuccessful excursions to allow Lady Agnew to rest and convalesce were undertaken; only short walks were embarked on and, if a longer stroll was anticipated, a bath chair would be used.[23] Historian Julia Rayer Rolfe suggests that Lady Agnew’s ill-health may have been a form of neurasthenia, or a type of chronic fatigue syndrome as it is now termed, as the remedy advised for the condition in the nineteenth-century was rest.[33]

Later life and death

After the war Lady Agnew was more energised and her former general malaise was supplanted with a sense of independence and activity. Extravagant dinner parties and plush entertainments were no longer commonplace among the aristocracy although Lady Agnew continued as a hostess to her own relatives and friends together with those of her husband. She had purchased a motor vehicle while at Whitehill, and in 1920 undertook a two-day drive to Lochnaw despite having only a passing interest in the estate.[34]

There is speculation that the family may have met with financial difficulties resulting in an attempt to sell Lady Agnew’s portrait to the Trustees of the Frick Collection in 1922 but the offer was rejected by Helen Clay Frick.[35][f]The source states Lady Agnew was a widow at the time of the offer in 1922 but her husband did not die until 1928[36] The painting was sold in 1925 by Lady Agnew to the National Gallery of Scotland. Pockets of land on the Lochnaw estate had been sold in 1920; some of the Agnew family attributed the need to raise revenue to Lady Agnew’s extravagance but she did have her own financial interests through the inheritance she received from the Lyveden bequests.[34]

Lady Agnew died in London on 3 April 1932 after a prolonged period of ill health.[26][37] Pernicious anaemia is recorded as her cause of death although this is unlikely to have been the illness that affected her earlier life.[23] She is buried in the Lyveden family vault in Northamptonshire.[34]

Notes

| a | Anomalies appear concerning Lady Agnew’s date and year of birth: Cokayne gives 16 June 1860 but indicates she was the youngest daughter of Vernon;[3] a birth notice in the Morning Chronicle indicates her mother gave birth to a daughter on that date but does not specify any further detail;[4] on its website the National Galleries of Scotland gives 1864[5][6] and Christopher Baker, former Director of European and Scottish Art and Portraiture at the National Galleries of Scotland – now Editor of The Burlington MagazineMonthly publication covering the fine and decorative arts of all periods, founded in 1903.,[7] also gives 1864 whereas Sir John Leighton, Director-General of the National Galleries of Scotland, simply states she was fifteen years younger than her husband;[8] and historian Julia Rayer Rolfe has 15 May 1865.[2] |

|---|---|

| b | Rolfe quotes Lady Lyveden’s year of birth as 1808.[12] Until the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 the legal age of consent for females was 13.[13] |

| c | Thomas Radcliffe was a second cousin once removed of Nicholas Fazakerley.[19] |

| d | According to the details in the Complete Baronetage, her name was Mary Arabella Louisa.[3] |

| e | Morgan was visiting London to view his art collection at an exhibition in what is now the Victoria and Albert Museum, Kensington.[25] |

| f | The source states Lady Agnew was a widow at the time of the offer in 1922 but her husband did not die until 1928[36] |