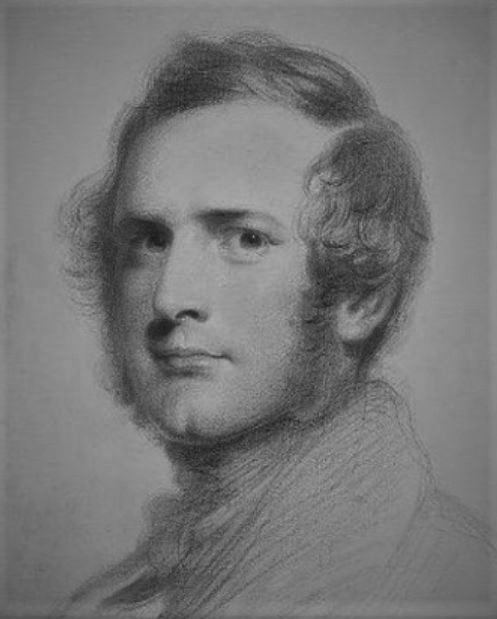

Hugh Seymour Tremenheere (1804–1893) was a career civil servant for the Home Office who, between 1839 and 1843, inspected schools and from 1843 to 1859 was the first Inspector of Mines. Tremenheere inspected other industries between 1855 and 1871.

Tremenheere married Lucy Bernal in April 1856. He retired in 1871 and was awarded a CB[a]Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath for his work in the public service. He died at Farnborough in Hampshire, in September 1893.

Family

Hugh Seymour Tremenheere, the eldest son of Walter Tremenheere and his wife, Frances, was born at Wootton House in Gloucestershire. His father, a well-connected naval officer born in Penzance, saw action in the American, French revolutionary, and Napoleonic wars. He was appointed lieutenant-governor of Curaçao, colonel-commandant of the Chatham division of the Royal Marines, and was briefly aide-de-camp to William IV.[1] Hugh Tremenheere was educated at Winchester College and New College, Oxford followed by grand tours of England and Scotland and Europe that lasted two years. He was a fellow of New College until 1856 when he married Lucy Bernal widow of Vicesimus Knox, Deputy Speaker of the House of Commons.[2] He died at Farnborough in Hampshire, in September 1893.[1]

Career

Tremenheere was called to the bar at the Inner Temple in 1834 and practiced for five years.[2]

Schools

Tremenheere turned down the offer of a law practice in Calcutta when he was appointed the first inspector to the Committee of Council on Education at a salary of £500 per annum in 1839.[2] He was sent to inspect the sites and structures of schools of the British and Foreign School SocietyEstablishments offering education to the children of Nonconformist parents, initially run by a single teacher using the monitorial system. (B&FSC) in Monmouthshire and Herefordshire and, while there, was called on to inquire into the causes of John Frost’s Newport rising.[1] He then inspected schools in Cornwall where he limited his investigation by sampling portions of the chief mining areas to uncover links between early deaths and occupation, and providing education that would enable the workers to do their duty rather than rise above their station in life.[3]

Tremenheere aligned himself with non-sectarianism, but the B&FSC resented his reports that criticised its use of the monitorial teaching method. After a critical report in 66 London schools it became apparent that inspector and society could not work harmoniously. The government was forced to settle the dispute with the B&FSC over inspection, and “promoted” Tremenheere to the Home Office as the first Inspector of Mines under the Mines Act, 1842

Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom prohibiting all females and boys under ten years of age from working underground in coal mines.

, with a £100 pay rise.[3]

Mines

Until 1843 mining was unregulated, and Tremenheere saw his prime duty as inspector was to see that the law was obeyed.[3] His sympathies were with the employers,[1] and he alerted them to his visits, detailing what would be inspected and “bespoke their co-operation”.[3] He sought co-operation but did nevertheless prosecute. Tremenheere oversaw compliance with the 1842 Act. When it was passed, 2400 women in Scotland and 800 in Lancashire were working underground. In 1845 there were still 200 in each place, and isolated prosecutions continued up to 1858.[4] Some but by no means all women found work on the surface as pit brow womenFemale surface labourers at British collieries. They worked at the coal screens on the pit brow (pit bank) at the shaft top until the 1960s. Their job was to pick stones and sort the coal after it was hauled to the surface. .

Tremenheere did not have the power to enforce safety regulations, and never went underground, but saw his main task as reporting on social conditions in the coalfields. He was not in favour of trade unionism and discouraged self-betterment for the working classes while encouraging colliery owners to build schools in which the working classes would learn to know their place.[1]

Visits to the coalfields of Belgium, France, and Germany, where he studied their mining laws, led him to recommend underground inspection for collieries in Britain, and he became the architect of the Mines Act, 1850. The 1850 Act provided for inspectors with technical qualifications to use their expertise to advise colliery managers and encourage best practice, rather than to force improvements. Tremenheere was firmly against the truck system and the payment of wages in public houses.[1]

Commissioner

As a Home Office Commissioner, Tremenheere reported on bleach works in 1855, lace works in 1861, and bakehouses. He served on royal commissions on the employment of children and young persons in both industry (1862–1867) and agriculture (1867–1871). As senior commissioner investigating the employment of children in industry and agriculture in 1862, he directed others and collated the results which led to an extension of the Factory Acts to cover many other industries, workshops and farms. Tremenheere retired in 1871 and was awarded a CB[b]Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath for his work in the public service.[1][5]