Wikimedia Commons

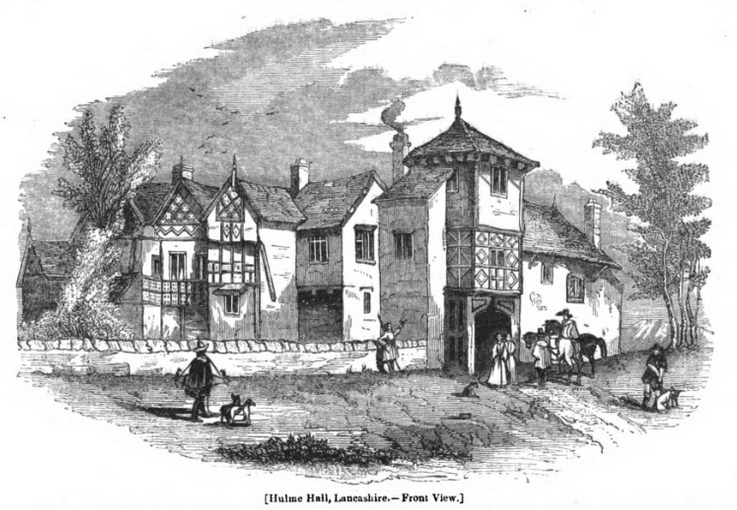

Hulme Hall was a manor house on the banks of the River Irwell in Hulme, Manchester, England. The half-timbered structure consisted of two-storey ranges built round a quadrangle, situated on a rise of red sandstone overlooking the river. It was well known for its gardens in the 18th century, but was in poor condition by the beginning of the 19th century, when it was being leased to various poor tenants.[1][2]

An article in The Penny MagazineIllustrated British magazine aimed at a working-class readership, published from 1832 until 1845. dated 9 March 1843 describes Hulme Hall as having “long been in a state of decay”, and recently demolished.[3] Some 16th-century carved oak panels had been removed to Worsley Old Hall in about 1833.[1][2]

Ownership

The hall was owned by John de Hulme during the reign of Henry II (1133–1189)[1] and by the de Rossindale family by the time of Edward I (1239–1307).[3] During the reign of Henry IV (1367–1413), it was owned by a branch of the family of Prestwich baronets and remained with them for centuries, with a five-year interlude when it was in the possession of Henry de Byrom. Sir Thomas Prestwich sold it to Sir Edward Mosley, 2nd Baronet, in 1660–1661. Mosley died without a direct heir at the age of 27 in 1665, and there then followed much litigation regarding his estate, complicated by various subsequent deaths.[1][4] In 1695 ownership passed to John Bland, a member of the Bland baronets and Member of Parliament for Lancashire from 1713 until 1727; Bland had married Mosley’s sole surviving heir, Anne.[1][4][5][a]Anne Bland was the founder of St Ann’s Church, Manchester. Hulme Hall was at that time considered to be “amongst the most stately residences in the parish of Manchester”.[6]

George Lloyd, a Fellow of the Royal Society, bought the hall in 1751.[1] In 1764 the property passed into ownership of Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, who paid a considerable sum to acquire it, thus allowing him to continue the construction of the canal that bears his name.[7][8]

Buried treasure

A hidden hoard of treasure was reputed to exist at the hall, although it has never been discovered. Supposedly, it belonged Sir Thomas Prestwich’s mother, who had induced him to lend large sums of money to King Charles I, with the assurance that she had sufficient buried treasure to amply repay him if the King could not. Unfortunately for Sir Thomas, his mother died of apoplexy before she could reveal to him the whereabouts of her fortune, leaving him in relative poverty.[8]

Notes

| a | Anne Bland was the founder of St Ann’s Church, Manchester. |

|---|

References

Bibliography

This article may contain text from Wikipedia, released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.