Isaac Fawkes (died 1732) (also spelt Fawks, Fawxs, Fauks and Faux) was an English conjuror and showman. The first record of Fawkes was an appearance by his son at Southwark Fair in 1722, but an advertisement earlier that year boasted that he had performed for King George II, so he was probably well-known in London before that time. He was one of the earliest magicians to present conjuring as an entertainment outside of the traditional fairground setting, and by skilful promotion and management of his act was able to amass fame and a considerable fortune. His simple entertainment was satirised alongside other popularist amusements by William Hogarth in 1723, but he continued to be patronised by fashionable society until his death in 1732. He formed a close professional relationship with the clock and automata maker Christopher Pinchbeck, and from the mid-1720s began to demonstrate Pinchbeck’s designs in shows in their own right and for magical effects in his conjuring act.

Popularity

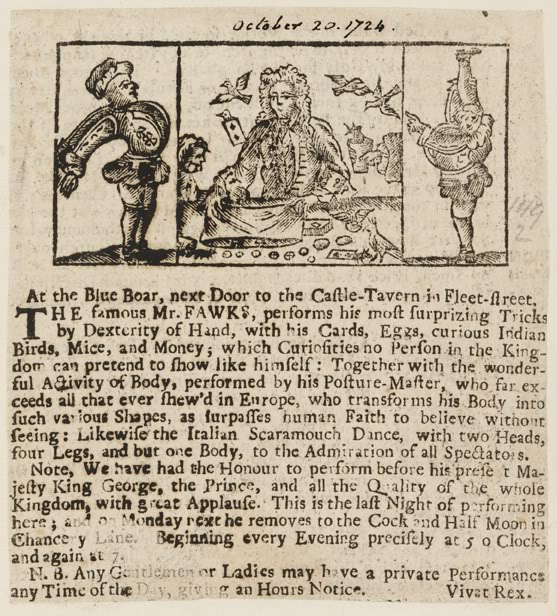

Nothing is known of Fawkes before early 1722, when an advertisement appeared announcing that his son would give a performance of tumbling at Southwark Fair, but he was probably well-established as a performer in London by then, as in March 1722 he had taken out an advertisement in which he mentioned his previous performances for George II,[1] in which he demonstrated:

The 12-year-old boy was Fawkes’s own son, who had been the tumbler at Southwark earlier in the year and became a regular fixture of Fawkes’s show as a “Posture Master” or contortionist; in later announcements Fawkes bragged that his son was the finest Posture Master in Europe. Because of the popularity of the contortionist act he took on another, younger boy, to perform a similar act, but “all different from what his own boy performs”.[3] Fawkes researcher Ricky Jay believes that a piece in The Daily CourantFirst British daily newspaper, first published on 11 March 1702. from 1711 may refer to Fawkes, as it mentions a posture master and many conjuring tricks that later became staples of Fawkes’s show.[4]

Wikimedia Commons

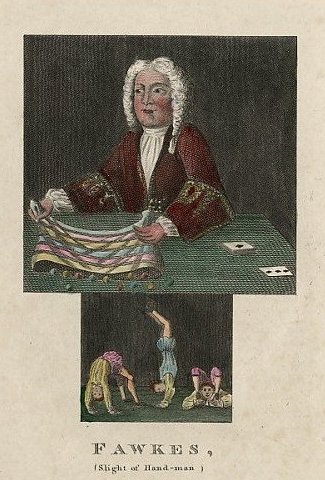

Fawkes was not the first fairground conjuror, and neither was he particularly innovative in his routines (although he did make extensive use of the recently invented Egg Bag),[5] but by consciously rejecting the association of conjuring with black magic and mysterious forces and making it clear that his show was not designed to defraud his audience, he was among the first to successfully market his act to fashionable society beyond the fairs. Fawkes eschewed the stereotypical voluminous cloak and hat of the traditional fair conjuror and instead presented himself in gentrified dress with a powdered wig and smart suit. His act was squarely presented as entertainment; he emphasised his skills of dexterity, and if he did mention the dark forces it was only to mock those of his contemporaries who claimed a connection with the supernatural.[6] The anonymous author of Round About Our Coal Fire or, Christmas Entertainments identified the key to Fawkes’ success:

But not everyone was convinced of Fawkes’s honesty. In his Portraits, memoirs, and characters, of remarkable persons (1819) the author and publisher James Caulfield portrayed Fawkes as a fraudster:

Fawkes was a regular at the Southwark and Bartholomew fairs, where he gave up to six shows a day,[9] but his increasing popularity allowed him to establish himself in London outside the fair season. Early in 1723 he was working from the Long Room at the French Theatre next to the Opera House, Haymarket, where he gave a performance to the Prince and his retinue and was “handsomely rewarded”. By April 1723 he had moved to premises in Upper Moorfields, where he held performances from a large booth three times a day (at three, five and seven o’clock). After the fair season he had a booth at Tower Hill, and by December he had moved back to the Haymarket under the same roof as John James Heidegger’s masquerades and Handel’s operas.[10]

Fawkes made extravagant use of self-promotion through newspapers, journals, broadsheets and playbills, keeping the public informed not only of his forthcoming shows but also of his performances for the rich and famous, his successes, and his developing career.[11] He also employed a flexible pricing structure for his entertainments; the entrance fees for his shows varied between sixpence and two shillings depending on the audience and the location.[12]

Performance

One of Fawkes’s advertisements described his routine in some detail:

Fawkes established himself at the Old Tennis Court playhouse in James Street between Haymarket and Whitcomb Street for several years, long enough for it to become known popularly as Fawkes”s Theatre,[2] and announcements for his show while there showed that he was expanding its scope. He formed a close professional partnership with the Fleet Street clock and automata maker, Christopher Pinchbeck,[b]Pinchbeck was the inventor of the alloy of copper and zinc that still bears his name, a form of brass made to look like gold.[1] who was responsible for much of the apparatus that Fawkes employed from the late 1720s onwards.[1] The earliest record of Pinchbeck’s work appearing in Fawkes show is from a 1727 advertisement for the Temple of Arts:

nquote]… with two moving pictures, the first being a Consort of Musick performed by several figures playing on various instruments with the greatest Harmoney and truth of time, the other giving a curious prospect of the City and Bay of Gibraltor, with ships of war and transports in their proper motions, as tho’ in real action; likewise the Spanish troops marching thro’ Old Gibraltor. Also the playing of a Duck in the river and the Dog diving after it, as natural as tho’ alive. In this curious piece there are about 100 figures, all of which show the motions they represent as perfect as the life; the like of it was never seen in the world.[13][/quote]

Fawkes’s famous trick of producing an apple tree from seed which “bore ripe apples in less than a Minute’s Time” relied on Pinchbeck’s work and Fawkes slowly began to introduce demonstrations of some Pinchbeck’s automata into his show alongside his sleight-of-hand conjuring and his son’s contortionist display. Among Pinchbeck’s works were the Venetian Machine or Venetian Lady’s Machine, which appears to have been a forerunner of the scrolling dioramas that would become popular in London in the 19th century. Pinchbeck usually received little or no billing in Fawkes’s act and if he attended any of the performances or shows he did not do so on a regular basis, but the relationship between the two men seems to have been close as Fawkes slowly shifted the focus of his show towards demonstrations of Pinchbeck’s designs. He continued to appear at the London fairs and continued to perform his conjuring act, but rather than stressing his feats of dexterity he concentrated on tricks based around Pinchbeck’s designs and on displays of Pinchbeck’s automata and clocks in shows with various flowery titles such as the Grand Theatre of the Muses or Multum in Parvo.[1]

Fawkes’s adoption of Pinchbeck’s creations as part of the show allowed him to further distance himself from black magic and witchcraft. In the public’s eye he was more closely aligned to the travelling natural philosophers – early scientists who often demonstrated recent discoveries in the sciences in touring shows that were part education and part entertainment. But Fawkes would still invoke spirits for promotional effect; a 1726 advertisement for an appearance at Bristol Fair jokingly referred to his “whole Equipage”, which included “auxiliary Spirits and Demons, shut up in a Bottle for Conveniency of Carriage”.[14]

By 1726 Fawkes’s show included his Posture Master, Pinchbeck’s automata, Powell’s puppet show, and giant waxwork figures:

Hogarth’s satires

William Hogarth regarded the trend away from high art in favour of low theatrical entertainments such as those of Fawkes and Heidegger with disdain. Allusions to Fawkes’s show feature prominently in his first issued print Masquerades and Operas (or the Bad Taste of the Town) of 1723, in which he mocks the public for its taste for an “English Stage, Debauch’d by fool’ries”. Hogarth regarded Fawkes’s popularity as indicative of the mentality of the public. As part of his act Fawkes produced money from thin air by an act of sleight-of-hand, which Hogarth may have seen as analogous to the expectations of the investors in the South Sea Bubble, whom Hogarth had mocked earlier in his Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme.[15] Fawkes’s show appears again in Hogarth’s Southwark Fair, a print of which was issued together with A Rake’s Progress in 1735. Fawkes was dead by this time, and although it is generally considered that Hogarth used a little artistic license in depicting Fawkes’s booth as it had appeared in earlier times, it is impossible to say whether it is Fawkes or his son who appears in the scene; Hogarth scholar Ronald Paulson thinks it more likely to be the father.[16][c]Fawkes’s daughter-in-law, Belle Fawkes, who briefly flourished as an actress in the early 1740s, has been suggested as a possible model for the girl with the drum in the centre of this scene.[17]

But Hogarth’s satire seems to have little effect on Fawkes’s trade. By the time it appeared he was wealthy and no longer reliant on the income from performing, and in February 1724 had announced in the London Evening Post that he would retire at the end of that year’s fair season. Nothing further came of his threat to quit the business, and in July he was proposing to visit Bristol with his show.[3]

Death and legacy

Wikimedia Commons

While Fawkes was performing at a fair in 1731 a fire broke out in a neighbouring booth, frightening his wife Alice (died 1745) so badly that she had to go into an “early confinement”; whether the experience contributed to Fawkes’s own death on 25 May 1732 is unknown. He was buried at St Martin-in-the-Fields, Westminster, having amassed a considerable fortune to leave to Alice, reportedly £10,000, equivalent to about £1.75 million as at 2020.[1][d]Using the retail price index as calculated by MeasuringWorth.[18]

Pinchbeck’s younger son, Edward, took over management of the business together with Fawkes’s son, and the show initially appears to have continued to flourish under their stewardship. Edward married Fawkes’s widow on 17 November 1733.[1] That same year they exhibited clocks and automata as the Grand Theatre of the Muses at Bartholomew Fair, and gradually their attention switched more to puppetry and puppet shows.[19]

The illusionist Harry Houdini considered Isaac Fawkes to be the “cleverest sleight-of-hand performer that magic has ever known”.[1]

Notes

| a | Fawkes’s Christian name was forgotten until 1904, when the details of his burial were discovered by Harry Houdini in the records of St. Martin-in-the-Fields. |

|---|---|

| b | Pinchbeck was the inventor of the alloy of copper and zinc that still bears his name, a form of brass made to look like gold.[1] |

| c | Fawkes’s daughter-in-law, Belle Fawkes, who briefly flourished as an actress in the early 1740s, has been suggested as a possible model for the girl with the drum in the centre of this scene.[17] |

| d | Using the retail price index as calculated by MeasuringWorth.[18] |

References

Bibliography

This article may contain text from Wikipedia, released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.