Kidnapped is a historical fiction adventure novel by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson, written as a boys’ novel and first published in the magazine Young Folks from May to July 1886. The novel has attracted the praise and admiration of writers as diverse as Henry James, Jorge Luis Borges, and Hilary Mantel.[1] A sequel, Catriona, was published in 1893.

The story is set around real 18th-century Scottish events, notably the “Appin murder”, which occurred in the aftermath of the Jacobite rising of 1745. Many of the characters are real people, including one of the principals, Alan Breck Stewart. The political situation of the time is portrayed from multiple viewpoints, and the Scottish Highlanders are treated sympathetically.

Written in English with some dialogue in Lowland Scots, the novel’s full title is Kidnapped: Being Memoirs of the Adventures of David Balfour in the Year 1751: How he was Kidnapped and Cast away; his Sufferings in a Desert Isle; his Journey in the Wild Highlands; his acquaintance with Alan Breck Stewart and other notorious Highland Jacobites; with all that he Suffered at the hands of his Uncle, Ebenezer Balfour of Shaws, falsely so-called: Written by Himself and now set forth by Robert Louis Stevenson.

Biographical background, publication

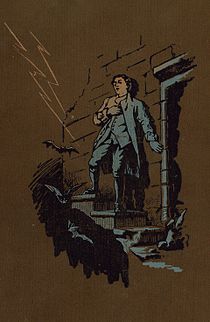

Kidnapped was first published in the magazine Young Folks from May to July 1886, and as a novel by Cassell in the same year.[2] Illustrations by W. Hole were added in an edition of 1887.[3]

Plot

The central character and narrator is 17-year-old David Balfour.[a]Balfour is Stevenson’s mother’s maiden name.[4] His parents have recently died, and he is out to make his way in the world. He is given a letter by the minister of his home parish of Essendean, Mr. Campbell, to be delivered to the House of Shaws in Cramond, where David’s uncle, Ebenezer Balfour, lives.

David arrives at the ominous House of Shaws and is confronted by his paranoid Uncle Ebenezer, who is armed with a blunderbuss. His uncle is also miserly, living on “parritch” and small ale, and the House of Shaws itself is partially unfinished and somewhat ruinous. But David is allowed to stay, and soon discovers evidence that his father may have been older than his uncle, thus making David the rightful heir to the estate. Ebenezer asks David to get a chest from the top of a tower in the house but refuses to provide a lamp or candle. David is forced to scale the stairs in the dark and realises that not only is the tower unfinished in some places, but the steps simply end abruptly and fall into an abyss. David concludes that his uncle intended for him to have an “accident” so as not to have to give over his nephew’s inheritance.

Wikimedia Commons

David confronts his uncle, who promises to tell him the whole story of his father the next morning. A ship’s cabin boy, Ransome, arrives the next day and tells Ebenezer that Captain Hoseason of the brig Covenant needs to meet him to discuss business. Ebenezer takes David to a pier on the Firth of Forth, where Hoseason is waiting, and David makes the mistake of leaving his uncle alone with the captain while he visits the shore with Ransome. Hoseason later offers to take them on board the brig briefly, and David complies, only to see his uncle returning to shore alone in a skiff. David is then immediately struck senseless.

David awakens, bound hand and foot, in the hold of the ship, and learns that the captain plans to sell him into slavery in the Carolinas. But the ship encounters contrary winds, which drive her back toward Scotland. Fog-bound near the Hebrides, they strike a small boat. All of the small boat’s crew are killed except one man, Alan Breck Stewart, who is brought on board the Covenant and offers Hoseason a large sum of money to drop him off on the mainland. David later overhears the crew plotting to kill Alan and take all his money. David and Alan barricade themselves in the round house, where Alan kills the murderous Shuan, and David wounds Hoseason. Five of the crew members are killed outright, and the rest refuse to continue fighting.

Hoseason has no choice but to give Alan and David passage back to the mainland. David tells his tale to Alan, who in turn states that his birthplace, Appin, is under the tyrannical administration of Colin Roy of Glenure, the King’s factor and a Campbell. Alan, who is a Jacobite agent and wears a French uniform, vows that should he find the “Red Fox” he will kill him.

The Covenant tries to negotiate a difficult channel without a proper chart or pilot, and is soon driven aground on the notorious Torran Rocks. David and Alan are separated in the confusion, with David being washed ashore on the isle of Erraid, near Mull, while Alan and the surviving crew row to safety on that same island. David spends a few days alone in the wild before getting his bearings.

David learns that his new friend has survived, and David has two encounters with beggarly guides: one who attempts to stab him with a knife, and another who is blind but an excellent shot with a pistol. David soon reaches Torosay, where he is ferried across the river, receives further instructions from Alan’s friend Neil Roy McRob, and later meets a catechist who takes the lad to the mainland.

As he continues his journey, David encounters none other than the Red Fox (Colin Roy) himself, who is accompanied by a lawyer, a servant, and a sheriff’s officer. When David stops the Campbell man to ask him for directions, a hidden sniper kills the King’s hated agent.

David is denounced as a conspirator and flees for his life, but by chance reunites with Alan. The youth believes Alan is the assassin, but Alan denies responsibility. Alan and David then begin their flight through the heather, hiding from government soldiers by day. As the trek drains David’s strength, his health rapidly deteriorates; by the time they are set upon by wild Highlanders who are sentries for Cluny Macpherson, an outlawed chief in hiding, the lad is barely conscious. Alan convinces Cluny to give them shelter, and David is tended by a Highland doctor. He soon recovers, though in the meantime Alan loses all of their money at cards with Cluny, only for Cluny to give it back when David practically begs for it.

When David and Alan resume their flight in cold and rainy weather, David becomes ill again, and Alan carries him on his back down the burn to reach the nearest house, fortuitously that of a Maclaren, Duncan Dhu, who is both an ally of the Stewarts and a skilled piper. David is bedridden and given a doctor’s care, while Alan hides nearby, visiting after dark.

In one of the most humorous passages in the book, Alan convinces an innkeeper’s daughter from Limekilns (unnamed in Kidnapped but called “Alison Hastie” in its sequel) that David is a dying young Jacobite nobleman, despite David’s objections, and she ferries them across the Firth of Forth. There, they meet a lawyer of David’s uncle’s, Mr. Rankeillor, who agrees to help David receive his inheritance. Rankeillor explains that David’s father and uncle had once quarrelled over a woman, David’s mother, and the older Balfour had married her, informally giving the estate to his brother while living as an impoverished schoolteacher with his wife. This agreement had lapsed with his death.

David and the lawyer hide in bushes outside Ebenezer’s house while Alan speaks to him, claiming to be a man who found David nearly dead after the wreck of the Covenant and says he is representing folk holding him captive in the Hebrides. He asks David’s uncle whether Alan should kill David or keep him. The uncle flatly denies Alan’s statement that David had been kidnapped but eventually admits that he paid Hoseason “twenty pound” to take David to “Caroliny”. David and Rankeillor then emerge from their hiding places, and speak with Ebenezer in the kitchen, eventually agreeing that David will be provided two-thirds of the estate’s income for as long as his uncle lives.

The novel ends with David and Alan parting ways on Corstorphine Hill; Alan returns to France, and David goes to a bank to settle his money.

Genre

Kidnapped is a historical romance, but by the time it was written attitudes towards the genre had evolved from an earlier insistence on historical accuracy to one of faithfulness to the spirit of a bygone age. In the words of a critic writing in Bentley’s Miscellany, the historical novelist “must follow rather the poetry of history than its chronology: his business is not to be the slave of dates; he ought to be faithful to the character of the epoch”.[5] Indeed, in the preface to Kidnapped Stevenson warns the reader that historical accuracy was not primarily his aim, remarking “how little I am touched by the desire of accuracy”.[6]

Stevenson presents the Jacobite version of the Appin murder in the novel,[7] but sets the events in 1751, whereas in reality the murder occurred a year later.[8]

Major themes

A central theme of the novel is the concept of justice, the imperfections of the justice system and the lack of a universal definition of justice. To David justice means the restoration of his inheritance, whereas for Alan it means the death of his enemy Colin Roy of Glenure.

Literary critic Leslie Fiedler has suggested that a unifying “mythic concept” in several of Stevenson’s books, including Kidnapped, is what might be called the “Beloved Scoundrel”, or the “Devil as Angel”, “the beauty of evil”.[9] The Rogue in this instance is of course Alan, “a rebel, a deserter, perhaps a murderer … without a shred of Christian morality”.[10] Good nevertheless triumphs over evil, as in David Balfour’s case.

Literary significance and reception

Kidnapped was well received and sold well while Stevenson was alive. After his death many viewed it with scepticism, seeing it as simply a boys’ novel, but by the mid-20th century it had regained critical approval and study. While it is basically an adventure novel, it raises various moral issues, such as the nature of justice (discussed in the previous section) and the fact that friends may have different political viewpoints.

James Annesley case

Since some of the earliest reviews of Kidnapped in 1886, it has been thought the novel was structured after the true story of James Annesley, a presumptive heir to five aristocratic titles who was kidnapped at the age of 12 by his uncle Richard and shipped from Dublin to America in 1728. He managed to escape after 13 years and return to reclaim his birthright from his uncle in one of the longest courtroom dramas of its time.[11]

As the Annesley biographer A. Roger Ekirch says, “It is inconceivable that Stevenson, a voracious reader of legal history, was unfamiliar with the saga of James Annesley, which by the time of Kidnapped‘s publication in 1886 had already influenced four other 19th-century novels, most famously Sir Walter Scott’s Guy Mannering (1815) and Charles Reade’s The Wandering Heir (1873).”[11]

Edinburgh: City of Literature

As part of the events to celebrate Edinburgh becoming the first UNESCO City of Literature, 25,000 copies of Kidnapped were made freely available by being left in public places around the city in February 2007. Three versions were distributed in that way:[12]

- A new printing of Barry Menikoff’s edition of the novel.

- A retelling of the tale for children.

- A 2007 graphic novel version created by Alan Grant and Cam Kennedy. Translations of the graphic novel were also published in Lowland Scots and Scots Gaelic.