Wikimedia Commons

The Manchester computers were an innovative series of stored-program electronic computers developed during the 30-year period between 1947 and 1977 by a small team at the University of Manchester, under the leadership of Tom Kilburn.[1] They included the first stored-program computer, the first transistorised computer, and what was the fastest computer in the world at the time of its inauguration in 1962.[2]

The project began with two aims: to prove the practicality of the Williams tube, an early form of computer memory based on standard cathode ray tubes (CRTs); and to construct a machine that could be used to investigate how computers might be able to assist in the solution of mathematical problems.[3] The first of the series, the Small-Scale Experimental Machine

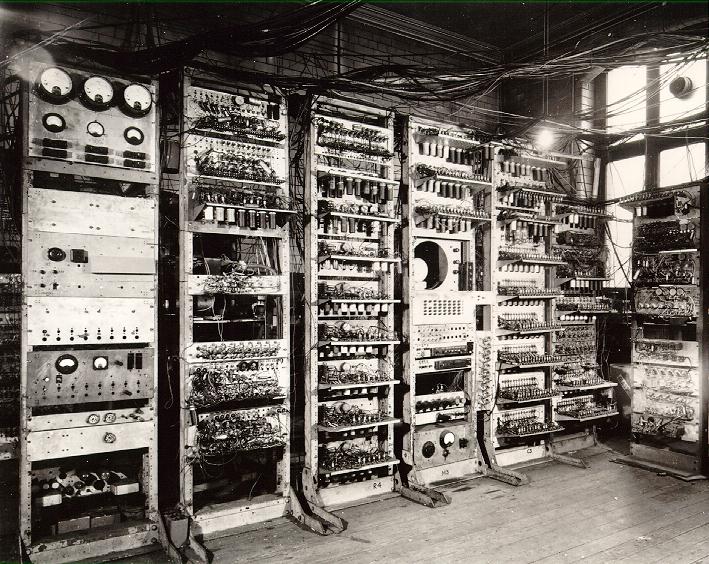

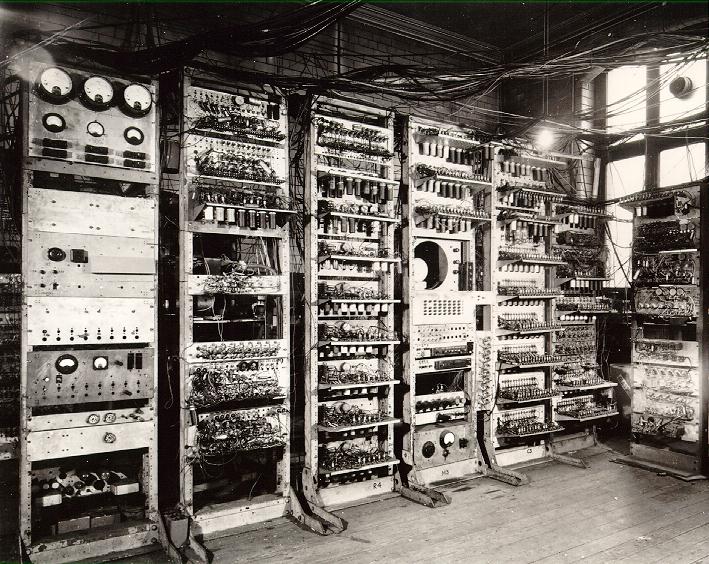

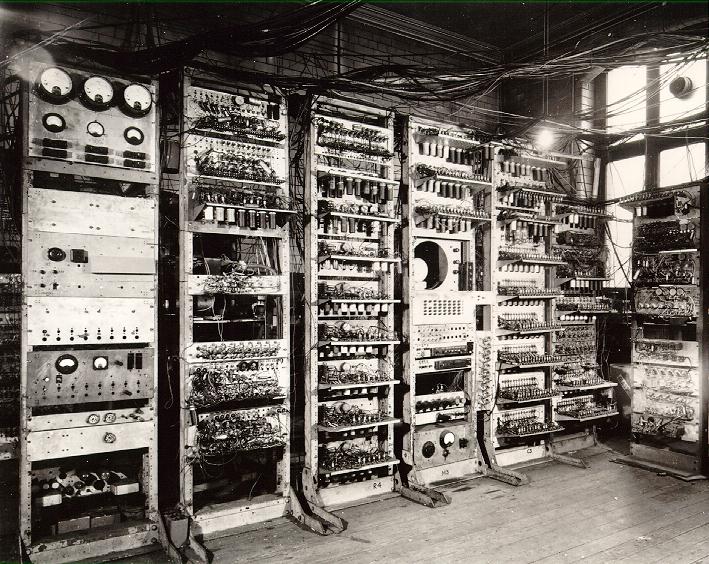

World’s first electronic stored-program computer. (SSEM), ran its first program on 21 June 1948.[4] As the world’s first stored-program computer, the SSEM, and the Manchester Mark 1

One of the earliest stored-program computers, developed at the Victoria University of Manchester from the Small-Scale Experimental Machine which went operational in 1948. developed from it, quickly attracted the attention of the United Kingdom government, who contracted the electrical engineering firm of Ferranti to produce a commercial version. The resulting machine, the Ferranti Mark 1, was the world’s first commercially available general-purpose computer.[5]

The collaboration with Ferranti eventually led to an industrial partnership with the computer company ICL, who made use of many of the ideas developed at the university, particularly in the design of their 2900 series of computers during the 1970s.

Small-Scale Experimental Machine

Main article: Small-Scale Experimental Machine

World’s first electronic stored-program computer.

The Manchester Small-Scale Experimental Machine (SSEM), also known as the Baby, was designed as a test-bed for the Williams tube, an early form of computer memory, rather than as a practical computer. Work on the machine began in 1947, and on 21 June 1948 the computer successfully ran its first program, consisting of 17 instructions written to find the highest proper factor of 218 (262 144) by trying every integer from 218 − 1 downwards. The program ran for 52 minutes before producing the correct answer of 131 072.[6]

The SSEM was 17 feet (5.2 m) in length, 7 feet 4 inches (2.24 m) tall, and weighed almost a ton. It contained 550 thermionic valves – 30 diodes and 250 pentodes – and had a power consumption of 3.5 kilowatts.[7] Its successful operation was reported in a letter to the journal Nature published in September 1948,[8] establishing it as the world’s first stored-program computer.[9] It quickly evolved into a more practical machine, the Manchester Mark 1

One of the earliest stored-program computers, developed at the Victoria University of Manchester from the Small-Scale Experimental Machine which went operational in 1948. .

Manchester Mark 1

Main article: Manchester Mark 1

One of the earliest stored-program computers, developed at the Victoria University of Manchester from the Small-Scale Experimental Machine which went operational in 1948.

Development of the Manchester Mark 1 began in August 1948, with the initial aim of providing the university with a more realistic computing facility.[10] In October 1948 UK Government Chief Scientist Ben Lockspeiser was given a demonstration of the prototype, and was so impressed that he immediately initiated a government contract with the local firm of Ferranti to make a commercial version of the machine, the Ferranti Mark 1.[5]

Two versions of the Manchester Mark 1 were produced, the first of which, the Intermediary Version, was operational by April 1949.[10] The Final Specification machine, which was fully working by October 1949,[11] contained 4,050 valves and had a power consumption of 25 kilowatts.[12] Perhaps the Manchester Mark 1’s most significant innovation was its incorporation of index registers, commonplace on modern computers.[13]

Meg and Mercury

As a result of experience gained from the Mark 1, the developers concluded that computers would be used more in scientific roles than pure maths. They therefore embarked on the design of a new machine which would include a floating point unit; work began in 1951. The resulting machine, which ran its first program in May 1954, was known as Meg, or the megacycle machine. It was smaller and simpler than the Mark 1, as well as quicker at solving maths problems. Ferranti produced a commercial version marketed as the Ferranti Mercury, in which the Williams tubes were replaced by the more reliable core memory.[14]

Transistor Computer

Work on building a smaller and cheaper computer began in 1952, in parallel with Meg’s ongoing development. Two of Kilburn’s team, Richard Grimsdale and D. C. Webb, were assigned the task of designing and building a machine using the newly developed transistors instead of valves. Initially the only devices available were germanium point-contact transistors, less reliable than the valves they replaced but which consumed far less power.[15]

Two versions of the machine were produced. The first was the world’s first transistorised computer,[16] which became operational in November 1953.[17] The second version was completed in April 1955. The 1955 version used 200 transistors, 1,300 solid-state diodes, and had a power consumption of 150 watts. The machine did however make use of valves to generate its 125 kHz clock waveforms and in the circuitry to read and write on its magnetic drum memory, so it was not the first completely transistorised computer, a distinction that went to the Harwell CADET of 1955.[18]

Problems with the reliability of early batches of transistors meant that the machine’s mean time between failures was about 90 minutes, but that improved once the more reliable junction transistors became available.[19] The Transistor Computer’s design was adopted by the local engineering firm of Metropolitan-Vickers in their Metrovick 950Early transistorised computer built by Metropolitan-Vickers, first operational in 1956., in which all the circuitry was modified to make use of junction transistors. Six Metrovick 950s were built, the first completed in 1956. They were successfully deployed within various departments of the company and were in use for about five years.[16]

Muse and Atlas

Development of MUSE – a name derived from “microsecond engine” – began at the university in 1956. The aim was to build a computer that could operate at processing speeds approaching one microsecond per instruction, one million instructions per second.[20] Mu (or µ) is a prefix in the SI and other systems of units denoting a factor of 10−6 (one millionth).

At the end of 1958 Ferranti agreed to collaborate with Manchester University on the project, and the computer was shortly afterwards renamed Atlas, with the joint venture under the control of Tom Kilburn. The first Atlas was officially commissioned on 7 December 1962, and was considered at that time to be the most powerful computer in the world, equivalent to four IBM 7094s.[21] It was said that whenever Atlas went offline half of the UK’s computer capacity was lost.[22] Its fastest instructions took 1.59 microseconds to execute, and the machine’s use of virtual storage and paging allowed each concurrent user to have up to one million words of storage space available. Atlas pioneered many hardware and software concepts still in common use today including the Atlas Supervisor, “considered by many to be the first recognisable modern operating system”.[23]

Two other machines were built: one for a joint British Petroleum/University of London consortium, and the other for the Atlas Computer Laboratory at Chilton near Oxford. A derivative system was built by Ferranti for Cambridge University, called the Titan or Atlas 2, which had a different memory organisation, and ran a time-sharing operating system developed by Cambridge Computer Laboratory.[22]

The University of Manchester’s Atlas was decommissioned in 1971,[24] but the last was in service until 1974.[25] Parts of the Chilton Atlas are preserved by the National Museums of Scotland in Edinburgh.

MU5

MU5 was designed to be about 20 times faster than Atlas, and was optimised for running compiled programs rather than hand-written machine code, something that contemporary computers were unable to do efficiently. A major factor in the MU5’s much-improved performance over its predecessors was its incorporation of associative memory, which greatly speeded up access to its main store.[26]

Work on MU5 started in 1966. The Science Research Council (SRC) awarded Manchester University a five-year grant of £630,466 in 1968, equivalent to about £12 million as at 2023,[a]Calculated using the GDP deflator.[27] to develop the MU5, and ICL made its production facilities available to the university. Development began in 1969, and by 1971 the design team had grown from its initial nucleus of six members of the university’s computer science department to 16, supported by 25 research students and 19 ICL engineers.[28]

MU5 was fully operational by October 1974, coinciding with ICL’s announcement that it was working on the development of a new range of computers, the 2900 series. ICL’s 2980 in particular, first delivered in June 1975, owed a great deal to the design of MU5,[29] which was in operation at the university until 1982.[30]

MU6

MU5 was the last large-scale machine to be designed and built at Manchester University. The development of its successor, MU6, was funded by a grant of £219,300 awarded by the SRC in 1979, equivalent to about £1.15 million as at 2023.[30][b]Calculated using the GDP deflator.[27] MU6 was intended to be a range of processors with MU6-V at the top end and a personal processor, MU6-P, at the bottom. Only MU6-P and a mid-range processor, MU6-G, were ever produced, and ran between 1982 and 1987.[2] The university did not have the resources to build the remaining machines in-house, and the system was never commercially developed.

Chronology of developments

| Year | University prototype | Year | Commercial computer |

| 1948 | Small-Scale Experimental Machine, aka “Baby”, which evolved into the Manchester Mark 1 | 1951 | Ferranti Mark 1 |

| 1953 | Transistor computer | 1956 | Metrovick 950 |

| 1954 | Manchester Mark II a.k.a. “Meg” | 1957 | Ferranti Mercury |

| 1959 | Muse | 1962 | Ferranti Atlas, Titan |

| 1974 | MU5 | 1974 | ICL 2900 series |