Wikimedia Commons

Manchester Liners was a cargo and passenger shipping company founded in 1898, based in Manchester, England. The line pioneered the regular passage of ocean-going vessels along the Manchester Ship Canal. Its main sphere of operation was the transatlantic shipping trade, but the company also operated services to the Mediterranean. All of the line’s vessels were registered in the Port of ManchesterCustoms port in North West England, created on 1 January 1894 and closed in 1982. Customs port in North West England, created on 1 January 1894 and closed in 1982. , and many were lost to enemy action during the First and Second World Wars.

A successful switch from traditional to container shipping in 1968 was relatively short-lived, as the subsequent introduction elsewhere of much larger container ships meant that the company’s vessels, which were restricted to a maximum length of 530 feet (160 m) imposed by the ship canal’s lock chambers, could no longer compete economically. The line ceased operations in 1985.

Early history

Wikimedia Commons

The opening of the Manchester Ship Canal in 1894 made it possible for large ocean-going ships to sail directly into the heart of Manchester. But because of opposition from cartels of ship-owners based at Liverpool and other ports in the United Kingdom, shipping lines were slow to introduce direct services to the new Port of ManchesterCustoms port in North West England, created on 1 January 1894 and closed in 1982. Customs port in North West England, created on 1 January 1894 and closed in 1982. , which found it difficult to compete against the established ports.[1] New trading routes from Manchester to West Africa and Mediterranean ports were countered by the established shipping conferences sharply reducing their own charges and by inducing their customers to sign binding contracts. In some cases, after achieving their aims, the cartels re-imposed their old charges.[2] To help counter these “sharp practices”, Sir Christopher Furness, of Furness Withy & Company, proposed in 1897 that a Manchester-based shipping line should be formed to encourage the use of the Manchester Ship Canal and docks. The public prospectus for Manchester Liners Ltd (ML) was issued on 10 May 1898, with an authorised share capital of £1 million. Furness’ company became the largest shareholder, and he was appointed chairman. Other directors included representatives from the Ship Canal company and Salford Borough Council.[3] Robert Burdon Stoker, a director of Furness Withy, was appointed as ML’s first managing director.[4]

Initial operations 1898–1914

Manchester Liners decided from the outset to make Manchester–Canada their prime route, with a secondary route to the southern United States cotton ports of New Orleans and Galveston. Other lesser, sometimes seasonal routes, were added later. Two 1890-built 3,000 gross registered ton (grt) ships were bought for £60,000 in May 1898, and renamed Manchester Enterprise and Manchester Trader. The Trader made the shipping line’s first voyage, setting out from Avonmouth for Montreal on 26 May, before docking in Manchester with a cargo of grain.[5]

The two secondhand vessels were joined in January 1899 by the newly built Manchester City of 7,696 grt, constructed by Raylton Dixon & Co of Middlesbrough. This steamship carried 1,170 long tons (1,190 t) of coal, burned at 70 long tons (71 t) per day, giving a speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph), fast for her day.[6] She was a refrigerated vessel, designed to carry frozen meat and live cattle, and was claimed to be one of the largest meat-carrying ships then afloat.[7] She made a successful maiden voyage from Canada and up the new canal to Manchester, which she took two days to negotiate after stopping overnight at IrlamBuilt-up area in the City of Salford, Greater Manchester, England, lying on flat ground on the south side of the M62 motorway and the north bank of the Manchester Ship Canal. to give the crew a rest. The Manchester Guardian reported on 16 January 1899 that “there were many shakings of the head, not only in Liverpool, at the audacity of the attempt” and that “the canal pilots, on reaching Irlam, looked as if they had not been in bed for a week, as their eyes were bleared with exhaustion”.[8] The City discharged 450 cattle and 150 sheep at Manchester Corporation’s Foreign Animals Wharf near the Mode Wheel locks in Salford. With an overall length of 467 feet (142 m), she was by far the largest vessel to have ventured up the waterway, and her successful navigation disproved the claim of Liverpool owners that only ships of 350 feet (110 m) or less could safely reach Manchester. The vessel continued to Manchester docks for further unloading, where she was met by the Lord Mayor, accompanied by a band and a festive crowd.[6] This successful voyage did much to encourage other shipowners to use the new port.[9] On her first voyage to Halifax, Nova Scotia in March 1899, the City took nine days and sixteen hours; and arrived before the mail boat, which had left the Mersey twelve hours ahead of her.[10]

The ML fleet was joined by two new smaller 5,600 grt vessels, the Manchester Port and Manchester Merchant during 1899 and 1900, and further new vessels followed quickly thereafter. The basic sailing pattern to Canada was St John, New Brunswick, year-round and to Montreal when the St Lawrence River was ice-free.

Between 1899 and 1902, four Manchester ships and their crews were requisitioned by the United Kingdom government to transport troops, horses, and supplies to South Africa during the Boer War and its aftermath. Collecting points for horses and mules included Galveston and New Orleans (USA) and Buenos Aires and Montevideo in South America. Manchester Port made its second voyage to the Cape in 1900, then continued to Australia to take troops to the conflict.[6] On the first voyage after her return to ML, in January 1903, the first Manchester Merchant was lost while on passage from New Orleans to Manchester. A serious fire developed in her cotton cargo, and she was scuttled in Dingle Bay on the west coast of Ireland to douse the flames, but subsequently broke up in bad weather.[11]

By 1904 the line was operating fourteen steamships of between four and seven thousand tons,[12] several built by the associated Furness Withy shipyards.[13] Services to ports in eastern Canada were supplemented by regular sailings to Boston, Philadelphia, and the southern US cotton ports of New Orleans and Galveston. Between 1904 and 1908 ML deployed three vessels including the Manchester City to the River Plate route, serving other UK ports as well Manchester. The main return cargo was frozen and chilled meat, and the City set a record for the largest meat consignment up to that time.[14] Lord Furness, as he had become, died in 1912 and was succeeded as ML’s chairman by R. B. Stoker until his death in 1919.[4] ML’s fleet was maintained at fourteen vessels during the last few years before the First World War. Eleven of their ships were deployed on the Canadian routes, carrying mainly manufactured goods outwards and meat and grain inbound.[15]

First World War

At the start of the war in July 1914, ML had a fleet of fifteen ships.[16] Most of the fleet continued to operate services to ports in eastern Canada and to USA including Baltimore, returning with war and other supplies. In August 1914, the Manchester Miller (1903) and Manchester Civilian (1913) were requisitioned as supply ships and sent with coal to the Falkland Islands to refuel the battlecruisers HMS Inflexible and HMS Invincible. As the Civilian was coaling the cruisers, the German vessels approached and the British warships cast off immediately to engage them.[17] In the ensuing battle Admiral Von Spee’s battleships Scharnhost and Gneisenau, plus escorting cruisers, were sunk.[18] The Civilian was later equipped with minesweeping gear. She returned in 1916 carrying supplies and equipment from Canada to the troops in France.

All vessels were fitted with defensive guns at the bow and stern. In June 1917 Manchester Port (1904) beat off a submarine attack with gunfire near Cape Wrath. Manchester Commerce (1899), outward-bound for Quebec City was sunk off northwest Ireland on 26 October 1914, with the loss of fourteen crew, becoming the first merchant ship to be sunk by a mine.[19] On 4 June 1917 the second Manchester Trader, en route from Souda Bay in Crete to Algiers, was engaged in a running battle with U-boat U 65 before she was captured and sunk near Pantellaria island, with the loss of one crew member.[20] The master, Captain F. D. Struss, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, and went on to complete forty years service with the line after surviving another sinking in the Second World War.[21] A further nine ships were sunk by U-boats, seven of the losses occurring in 1917.

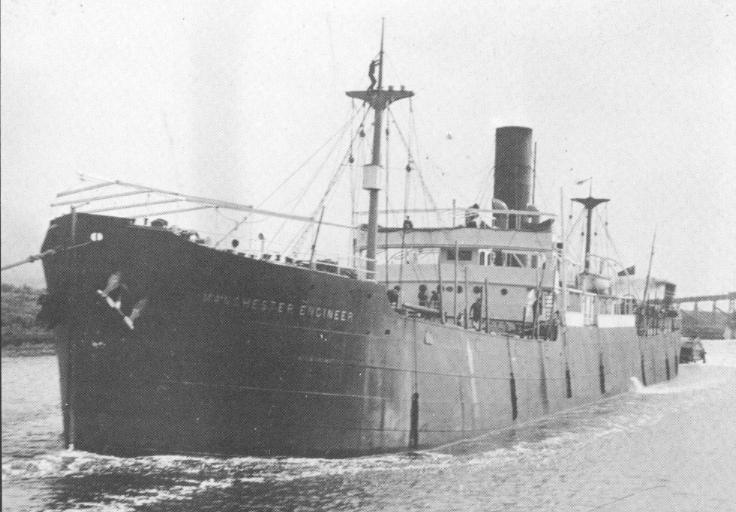

ML acquired seven ships between 1916 and 1918, four of which were sunk in 1917. Manchester Engineer, acquired secondhand in 1917, had a short but eventful career with ML. On 18 June, when bound for Archangel, she was chased by a U-boat but escaped when her naval escort arrived. On 16 August when sailing from the Tyne to St Nazaire with coal, she was torpedoed five miles off Flamborough Head and sunk. Manchester Division achieved fame on her maiden voyage from West Hartlepool to join a westbound Atlantic convoy at Plymouth when she rammed and sank a German submarine off Flamborough Head in October 1918. At the end of the war in November 1918, ML had twelve surviving vessels on strength.[22]

Peacetime operations 1919–1939

Wikimedia Commons

In 1921–22, ML’s fleet was augmented by two second-hand vessels. Sailings were resumed to New Orleans, and the Baltimore service was extended to Norfolk, Virginia. Some ships including the Manchester Civilian and Manchester Spinner became regular carriers in the coal trade from Sydney, Nova Scotia. The Civilian made several round trips from the USA to Japan in 1923, carrying relief supplies after the Japanese earthquake.[23] ML took delivery of the 7,930 tons steam turbine Manchester Regiment in 1922,[24] constructed on the Tees by the Furness Shipbuilding Company. This 12.5-knot (23.2 km/h; 14.4 mph) ship with a crew of sixty-five was the largest operated to date, carrying 512 cattle, plus hold cargo and was equipped with large derricks to assist in heavy goods handling.[25] The Regiment‘s record from the Mersey Bar to Quebec was seven days nine hours. In 1925 her captain won the gold-headed cane traditionally awarded each Spring to the master of the first ship to break through the St Lawrence ice to reach Montreal, a feat repeated later by several other ML captains.[26] ML’s old head office in Deansgate, Manchester became inadequate and was replaced in August 1922 by a purpose-built five-storey modern building in St Ann’s Square next to the Royal Exchange.[27]

The line acquired two new vessels in 1925, but later that year its fortunes were adversely affected by competition from subsidised American firms on the North Atlantic routes; ML disposed of seven ships between late 1925 and 1930,[28] reducing its fleet to ten vessels. The Regiment steamed 160 miles through a gale in 1929 to reach the sinking Glasgow steamer Volumnia. A lifeboat was launched to rescue the crew of forty-five. On return home, King George V awarded the Regiment‘s lifeboat crew the Silver Medal for Gallantry in Saving Life at Sea and Manchester’s Lord Mayor presented a silver salver from the Board of Trade to Captain Linton.[27] In 1933, during the Great Depression, several ships were laid up; the Manchester Merchant of 1904 was disposed of for breaking up and the Manchester Civilian was sold to Greek owners. The public sailing programme for the 1933 summer season listed six ships as allocated to the weekly “Fast Freight Service” to Quebec and Montreal. The six steamers were advertised as being “fitted with fan or forced ventilation and all have cold storage accommodation”.[29] Most vessels were also able to carry up to twelve passengers. After a ten-year gap, three new vessels were commissioned between 1935 and 1938 as trade started to recover, maintaining the fleet at ten ships. The trio were equipped with automatic stokers for their coal-fired boilers and had greatly improved accommodation for the passengers and the crew.[30]

Second World War

ML had ten vessels at the start of World War II, but early in the conflict lost Manchester Regiment in December 1939, when outbound with general cargo for St John, New Brunswick. She was proceeding without lights when she was run down by the Pacific Steam Navigation’s Oropesa, which had been detached from an eastbound convoy. While the ML fleet continued to be deployed on the North Atlantic routes during the war,[31] the company’s vessels also undertook a wide variety of roles elsewhere during the conflict. Manchester City became a minelayer, then a naval auxiliary ship, working in the Far East. Manchester Progress was one of the last ships to leave Rangoon in 1941 before the Japanese conquest of Burma.[32] Manchester Commerce (1925) was deployed on Mediterranean convoys in 1942/43 and next year transported mules from South Africa to India for the Burma Campaign. Manchester Trader (1941) was fitted with extra crew quarters for use as a commodore ship on Atlantic convoys. Except for two supply runs to Bone, Algeria, she remained in the Atlantic theatre and served ML until 1963. Manchester Brigade, having survived the first World War, was sunk on 26 September 1940 after being torpedoed by U-137 when bound for Montreal in convoy off Malin Head, to the north of Ireland; fifty-eight crew were lost.[33]

Manchester Merchant, completed in May 1940, quickly became involved in “Operation Fish”, transporting Britain’s gold reserves to Canada, making two voyages with bullion valued in total at £4.5 million.[34] In late 1942 she was deployed on Operation Torch as a supply ship to North Africa. On 25 February 1943, she was torpedoed by U-628 while part of an outbound Atlantic convoy; thirty-six of the crew of sixty-five including gunners were lost, but Captain Struss again survived, and received the OBE.[35] Manchester Division (1918) bound for Table Bay was directed to assist the Blue Star Line’s Dunedin Star which had beached on Namibia’s rugged coast. The Division stood by in heavy swell for three days, rescuing forty passengers and crew, before taking them to Cape Town.[31] Manchester Citizen (1925) was also sunk by a U-boat, whilst on passage to Lagos on 9 July 1943 after surviving several supply runs for the Eighth Army. The last vessel to be “lost”, albeit deliberately, was Manchester Spinner (1918), which had taken military supplies to India in 1942. On 7 June 1944, shortly after D-Day, manned by a volunteer crew, she led a line of Mulberry Harbour blockships and was sunk off Juno Beach Normandy to act as a breakwater, whilst troop reinforcements and stores were landed on the beaches. Her superstructure was then armed with anti-aircraft guns.[36]

Peacetime operations 1945–1968

At the war’s end, ML had a fleet of eight vessels built between 1918 and 1943, and these continued to operate the traditional service to eastern Canada for a further two years before new vessels could be acquired.[37] In 1946 the Manchester Shipper became the first merchant ship to be fitted with radar, and to navigate the St Lawrence with its aid. In the same year the company carried Manchester’s Lord Mayor and party to Canada on a goodwill and trade mission.[35] Manchester Exporter was sold in 1947 and replaced by the newly built larger Manchester Regiment. Two further 7,000 ton 14-knot (26 km/h; 16 mph) ships were commissioned in 1952, which meant that the Manchester Division, veteran of both wars, could be sold for scrap after a record thirty-five years service with the line.[38] In 1952, Robert B. Stoker, grandson of the second chairman, became the third generation of his family to be appointed an executive director of ML. He had joined the line in 1932 and in turn became chairman in 1968.[39]

Manchester Shipper was used to transport WWII German aircraft to Canada. It left Ellesmere Port on 23 August 1946 arriving in Montreal 1 September. Its cargo included two Me 262s (WNr500210, WNr111690). Manchester Commerce also carried Second World War German aircraft to Canada, leaving Seaforth Docks on 26 August and arriving on 9 September with two He 162s (WNr 120076, WNr 120086) and two Me 163s (WNr191454, WNr191914).[40] The vessel featured in the 1961 film A Taste of Honey.

ML contracted Cammell Laird of Birkenhead to build two smaller vessels of 1,800 tons. Commissioned in 1952, they were named the Manchester Pioneer and Manchester Explorer; they were joined by the secondhand 1,400-ton Manchester Prospector. The trio were the first of a size able to pass through the restricted-size canals and locks leading directly to Toronto and the other Great Lakes ports as far as Detroit, Michigan.[41] This initiative, the first by a British line, and taken well ahead of the 1959 completion of the Saint Lawrence Seaway, gave the line a head start in the direct trade to the Midwest ports. During the winter months, when thick ice prevented navigation on the lakes, the trio were employed elsewhere, sometimes on charter to other lines.[42]

Manchester Progress, 5,620 grt, opened a regular mid-summer service to Churchill, Manitoba on Hudson Bay in 1954, during the short ice-free season, bringing back grain shipped to the port by rail from the Canadian Prairies. Captain F. Struss, survivor of sinkings in both wars, retired in March 1954 after forty years service, the last ML Commodore who had gained his master’s ticket in sail. That same year the Great Lakes service was extended to Chicago, and ML’s pre-1914 service to the southern US ports of Charleston, Savannah, and Jacksonville was resumed.[43]

A USAF RB-36 “Peacemaker” ten-engined strategic bomber suffered engine fires on 5 August 1954, while en route from Travis AFB California to RAF Lakenheath Suffolk. The crew of twenty-three were ordered to bail out 450 miles (720 km) west of Ireland at 03:40. The Manchester Shipper, inbound from Montreal, and the outbound Manchester Pioneer, diverted to the scene and despite bad weather were able to rescue the four surviving crew. The USAF’s HQ Third Air Force sent messages commending the ship masters and crews efforts under adverse circumstances.[44]

ML’s first two motor vessels, with engines and accommodation located aft, were commissioned in April 1956. The Manchester Vanguard and Manchester Venture, 1,662 grt, were designed for the Great Lakes service. Two larger motor vessels, the Manchester Faith and Manchester Fame, 4,460 grt, were commissioned in April 1959, and the Faith quickly became the first commercial vessel to transit the newly opened St Lawrence Seaway with its larger locks.[45]

Two ML vessels were involved in a successful mid-Atlantic rescue of airliner passengers on 23 September 1962. A Flying Tiger Line Lockheed Super Constellation was en route from McGuire AFB New Jersey to Frankfurt Airport with 76 persons aboard. Two out of four engines failed and the airliner changed course for Shannon Airport Ireland. After a further hour, a third engine failed and Captain John Murray made a successful ditching in darkness 560 nautical miles (1,040 km; 640 mi) west of Shannon. All occupants evacuated the aircraft before it sank. The larger Manchester Progress acted as a radio relay ship, while Manchester Faith picked up forty-eight survivors. The other twenty-eight persons on board the aircraft were lost when their rafts sank in heavy seas.[46]

Switch to containers 1968–1978

Manchester Liners House, the company’s new headquarters in Salford Docks, was officially opened on 12 December 1969 by the High Commissioner for Canada. The design was advanced for its day and it remains basically unchanged today except for re-glazing. The unusual curved facade of the ten-storey building was designed to echo the bridge shape of the Manchester Miller.[47] Later renamed Furness House, it was built on the former Manchester Ship Canal railway sidings between Nos. 8 and 9 Docks.

By the late 1960s rising shore costs, dock workers strikes, restrictive practices on both sides of the Atlantic, and subsidised competition from American shipping lines, persuaded Manchester Liners to switch its future fleet to container ships only. An example of the delaying effect of the strikes in the Canadian ports, with consequent impact on operating costs, was an extended ninety-day return voyage to Quebec City in early 1967 by the new Manchester Progress.[48]

Wikimedia Commons

Initially, three new ships were ordered from Smiths Dock Company in Middlesbrough, the first of which, Manchester Challenge, was delivered in 1968, becoming the first British-built and operated cellular container ship.[49] The Challenge and her two sisters Manchester Courage and Manchester Concorde were followed from the Tees in 1971 by the Manchester Crusade.[50] UK manufacturers supplied 10,000 containers. The four ships each had the capacity to carry five hundred 20-foot (6.1 m) containers, all of them below deck. A new regular container route started in November 1968, with a twice-weekly service to Montreal, where the containers were transferred to smaller vessels which could navigate to the ports of the Great Lakes.[51] The four new powerful (16,000 hp) 19.5-knot (36.1 km/h; 22.4 mph) vessels were constructed to a standard exceeding Lloyds class 1 ice-stiffening, with additional aft protection over the rudder to permit reversing through ice.

On her second voyage in early 1969, Manchester Challenge lived up to her name by entering the heavily iced Montreal harbour, discharging, reloading and departing only two days late. Another thirty-seven conventional vessels were stuck at the port for a month.[50] The quartet’s ice-breaking capability often resulted them in leading a convoy of other vessels into Montreal during the winter months. The four ships of 12,039 gross tons were of the maximum size able to navigate the Manchester Ship Canal.[51]

To obtain the greatest operational efficiency, ML constructed two dedicated container terminals with their own gantry cranes, spreaders etc. The Manchester terminal was built on an open site next to the western end of No. 9 Dock. A second container berth was added in 1972.[52] The other terminal was created at Montreal, with similar equipment, where the containers were trans-shipped to a dedicated liner train operated by Canadian National Railways, which carried them onwards to Toronto and further destinations.[50]

ML inaugurated a container service to the Mediterranean in 1971 using smaller ships. Initial destinations included Malta, Cyprus and Israel. Later in the decade, the countries served were extended to include Italy, Greece, Lebanon and Syria. To further improve service to shippers, two large road hauliers were acquired in 1971 and 1972, enabling a “door-to-door” container operation to be introduced. Facilities for container storage and repair were also acquired.[53] Following its successful pioneering of the UK container trade, ML was given the Queen’s Award for Export in 1971, the first to be given to a shipping company; every ship in the fleet flew the award flag.[52]

In 1974 ML carried 783,000 long tons (796,000 t) out of the total 2,900,000 long tons (2,900,000 t) of dry cargo handled on the ship canal (27%). During the same year, ML acquired Manchester Dry Docks Ltd, which operated three large and one small dry docks on the canal adjacent to MLs berths in Salford Docks. These facilities assisted greatly in keeping the fleet fully operational.[54] Manchester Challenge completed her 100th round voyage to Montreal in 1975 having carried 95,000 containers weighing 1,440,000 long tons (1,460,000 t) a distance of 554,000 miles (892,000 km) – the equivalent of a round trip to the moon.[55] During 1976 MLs Manchester to Canada route had three sailings per week.[56]

Decline and closure

Manchester Liners had been partly owned by Furness Withy from the beginning, and became a subsidiary in 1970.[57] Furness Withy was itself taken over in 1980 by the C. Y. Tung Group of Hong Kong. Robert B. Stoker retired in 1979 as Chairman of Manchester Liners after 47 years service with the company.[58]

Severe competition following the building of excess container shipping capacity by many companies badly affected ML’s trade and profitability. The company’s vessels were by then smaller than average in the industry, leading to higher operating costs per unit of cargo carried. Their operations were also severely affected during the mid-1970s by official and unofficial strikes by dock workers.[59] The service to Canada ended in 1979, and by the early 1980s only five “Manchester” ships remained – the 30,000 ton container vessel Manchester Challenge and four 1,600–4,000 ton vessels: Manchester Crown, Manchester Trader, Manchester Faith and Manchester City. The line had by then ceased using the Port of Manchester, and the four smaller vessels were operating to the Mediterranean out of Ellesmere Port, 33 miles (53 km) closer to the sea, on the lower reaches of the ship canal.

In 1981 ML, jointly with the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company and the Dart Container Line, instituted a weekly containership service from Felixstowe, Suffolk, to Montreal. MLs contribution to the service was the large Manchester Challenge.[60] The last of Manchester Liners’ ships was sold in 1985, and in 1988 the services formerly operated by the company were taken over by the Orient Overseas Container Line, successor to the Tung Group.[61]

Ship naming, house and flag colours

| |

Manchester Liners flag Wikimedia Commons | Funnel colours Wikimedia Commons |

The company’s ship-naming policy throughout its 87-year period of operations was to use its home port’s name plus a suffix word, often a trade or occupation. The most frequently used name was Manchester Trader, applied to six different vessels between 1898 and cessation of operations in 1985.[62] Some names used appropriately during the First World War, such as Manchester Hero, Manchester Brigade and Manchester Division were not reused after the disposal or loss of those vessels. Some ships operated short-term or on charter retained their original names and did not receive the Manchester prefix.

From the earliest days, the line’s colours were: funnels – dark red with black top and thin black band; hulls – black with white boot topping.[63] During the Second World War, ships were painted in battleship grey and the names were deleted for security, except when in friendly ports. From the 1960s onwards, some ships’ hulls were painted light grey and others red.[49]

The line’s flag colours were a red oval, placed horizontally, with white “ML” lettering in the centre, imposed on an overall white background.

References

- p. 56

- p. 5

- p. 9

- p. 7

- p. 18

- p. 19

- p. 115

- p. 10

- p. 27

- p. 11

- p. 15

- pp. 58–60

- p. 112

- p. 13

- p. 171

- p. 10

- p. 15

- p. 23

- p. 21

- p. 25

- p. 16

- pp. 17–23

- p. 17

- p. 113

- p. 29

- p. 24

- p. 18

- p. 25

- p. 26

- p. 27

- p. 19

- p. 116

- p. 27

- p. 32

- p. 21

- pp. 28–29

- p. 12

- p. 29

- p. 3

- pp. 23–25

- pp. 33–35

- p. 27

- pp. 26–27

- p. 38

- p. 480

- pp. 47–53

- p. 39

- p. 43

- p. 44

- p. 111

- p. 55

- p. 54

- p. 58

- p. 60

- p. 12

- p. 53

- p. 67

- pp. 88–89

- p. 56

- p. 118

- pp. 58–64

- p. 46