Martha Bradley (fl. 1740s–1755) was a British cookery book writer. Little is known about her life except that she worked as a cook for more than thirty years, in the fashionable spa town of Bath, Somerset.

Martha’s only printed work, The British Housewife, was released as a 42-issue partwork between January and October 1756. It was then released in two-volume book form in 1758, but it is likely that Martha was dead before the partwork was published. The book follows the French style of nouvelle cuisine, which differentiates her different from other female cookery book writers at the time, who focused on the British or English style of food preparation. The work is well organised, and the recipes taken from other authors are amended, suggesting that she was a knowledgeable and experienced cook, able to improve on pre-existing dishes.

Although she is not well-known today, Martha Bradley’s biographer believes that she is perhaps one of the 18th-century’s most important cookery writers.[1] But because of the length of The British Housewife, more than a thousand pages, it was not reprinted until 1996, and as a result few modern writers have written on Martha or her work.

Life

What little is known of Martha Bradley’s life comes from her single publication, The British Housewife. In the 1740s she worked as a professional cook in the fashionable spa town of Bath, Somerset,[1] and had more than thirty years experience in the job.[2] The publisher of The British Housewife noted that all Martha’s papers had been stored with him; the food historian Gilly Lehmann has suggested that Martha was therefore probably dead by the time the work was published in the late 1750s. Included in the papers was a handwritten family recipe collection.[1]

Given the recipes shown in her work, it seems that Martha had read several contemporary cookery books, including Mary Eales18th-century writer on cookery and confectionery, author of Mrs Mary Eales's Receipts (1718) (Mrs Mary Eales’s Receipts, 1718), Patrick Lamb (Royal Cookery, 1726 – the third edition), Vincent La Chapelle (The Modern Cook, 1733) and Hannah Glasse (The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, 1747).[1] These had all been changed and improved from the originals,[3] demonstrating that Martha was knowledgeable and skilled in her chosen occupation according to the food writer Alan Davidson.[4]

The British Housewife was first published as a partwork in 42 weekly editions,[5] possibly the first cookery book issued in that form;[6] the first issue was dated 10 January 1756. The weekly editions comprised “four large half-sheets of printing” costing 3d.[7] The weekly editions would have finished in October that year, and would have cost 10s. 6d in total.[5] The partworks were advertised across Britain, and in the text Martha advertised the other issues, telling readers “We have in our preceding Numbers given the Cook so ample Instruction for the roasting of all plain Joints of Meat … that she cannot be at a loss in any of them”.[8] A reviewer for the journal Petits Propos Culinaires considers that Bradley’s “scheme for the education of the cook and housewife was more thorough than any that had gone before.”[6]

The work was published in book form in 1758; its two volumes comprised more than 1200 pages.[3][9] Some works show conflicting dates. Virginia Maclean’s 1981 history A Short-Title Catalogue of Household and Cookery Books Published in the English Tongue, 1701–1800, puts the publication date at 1760,[10] but Arnold Oxford’s 1913 work English Cookery Books to the Year 1850 listed it as c. 1770.[11]

The British Housewife (1758)

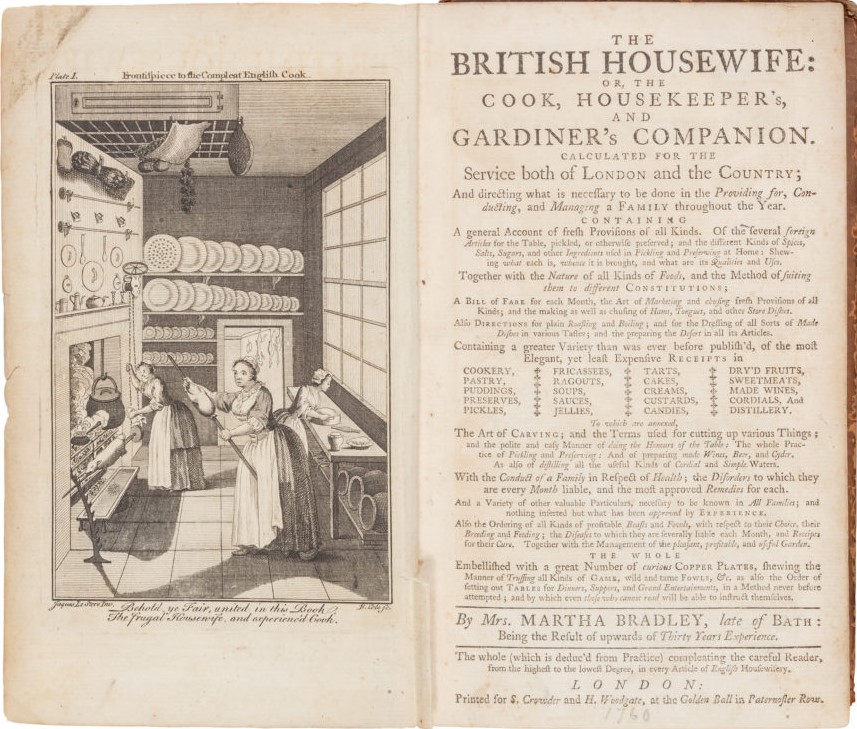

The title page of book version of The British Housewife, published in 1758,[a]The full title is The British Housewife or, the Cook, Housekeeper’s and Gardiner’s Companion. Calculated for the Service Both of London and the Country.[12] outlines that the work contains information on cookery, pastry, puddings, preserves, pickles, fricassees, ragouts, soups, sauces, jellies, tarts, cakes, creams, custards, candies, dried fruits, sweetmeats, wines, cordials and distilled spirits.[12] The book also contained a chapter on cures for common ailments, which included a recipe that included powdered earthworm to cure ague.[13] The work was divided into monthly sections,[14] and showed a “sophisticated organisation”, according to Davidson.[15]

Bradley described her aim for the book thus, “Our cook will be able to shew that an English Girl, properly instructed at first, can equal the best French Gentleman in everything but Expence.”[16] She was one of the first female cookery book writers in 18th-century England to write in support of the French style of nouvelle cuisine,[17] although she was also happy to criticise the approach for some dishes. At the end of a recipe for roast capon with herbs, she advises that adding a “raggoo” (a sauce[b]A “raggoo” was originally a rich garnish made from savouries in a rich sauce, a development introduced from France; the word comes from the French en ragoût.[18]) will make it more fashionable, but not improve it:[19]

French cuisine was not alone in facing Martha’s criticism; one of her recipes for roast pork discusses Teutonic animal husbandry practices: “The Germans whip him to Death, but they deserve the same Fate for their Cruelty; there is no Occasion for such Barbarity to make a dainty Dish”.[21]

The British Housewife contains several illustrations throughout, including examples of how to truss cuts of game,[22] and examples of menus to have at various times through the year.[23] The frontispiece of the book shows three women working in a kitchen above the motto “Behold you fair, united in this book. The frugal housewife and the experienced cook.”[24][25] Economy and practicality are shown throughout her approach, according to the food historian Ivan Day.[26]

The scale of the book – at more than 1000 pages – ensured the work was not reprinted until 1996, and as a result few modern writers have written on Martha or her work.[6] Davidson, who considers The British Housewife “the most interesting of the 18th century English cookery books”, believes that “one has the feeling in reading … [Martha’s] work that here is a real person, communicating effectively with us across the centuries”.[27] Lehmann considers that Bradley’s personal involvement in developing the recipes stands out in the book.[1] Lehmann, writing in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography considers that:

Notes

| a | The full title is The British Housewife or, the Cook, Housekeeper’s and Gardiner’s Companion. Calculated for the Service Both of London and the Country.[12] |

|---|---|

| b | A “raggoo” was originally a rich garnish made from savouries in a rich sauce, a development introduced from France; the word comes from the French en ragoût.[18] |