Mary Toft (née Denyer; c. 1703–1763), also spelled Tofts, was an English woman from Godalming, Surrey, who in 1726 became the subject of considerable controversy when she tricked doctors into believing that she had given birth to rabbits.

In 1726 Mary became pregnant, but following her reported fascination with the sighting of a rabbit, she miscarried. Her claim to have given birth to various animal parts prompted the arrival of John Howard, a local surgeon, who investigated the matter. He delivered several pieces of animal flesh and duly notified other prominent physicians, which brought the case to the attention of Nathaniel St. André, surgeon to the Royal Household of King George I. St. André concluded that Mary’s case was genuine but the King also sent surgeon Cyriacus Ahlers, who remained sceptical. By then quite famous, Mary was taken to London, where she was studied in detail. Under intense scrutiny and after producing no more rabbits she confessed to the hoax, resulting in her imprisonment for fraud.

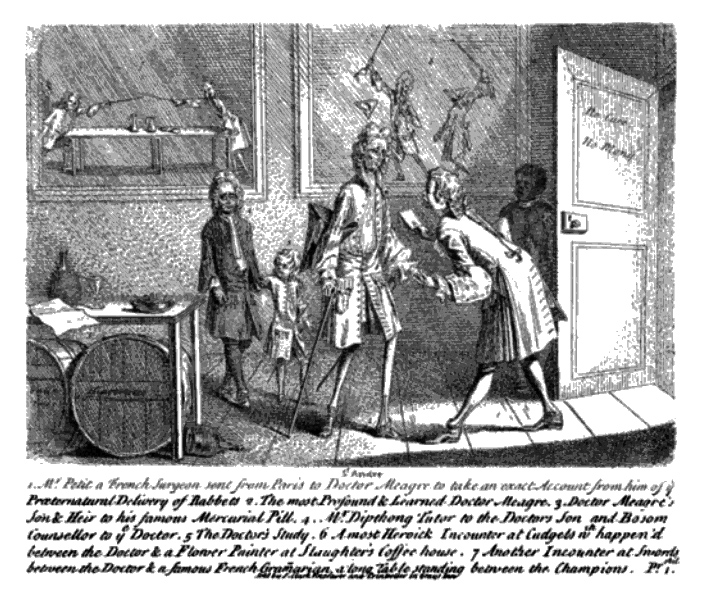

The resultant public mockery created panic within the medical profession and ruined the careers of several prominent surgeons. The affair was satirised on many occasions, not least by the pictorial satirist and social critic William Hogarth, who was notably critical of the medical profession’s gullibility. Mary was eventually released without charge and returned home.

Account

The story first came to the public’s attention in late October 1726, when reports began to reach London.[1] An account appeared in the Mist’s Weekly Journal, on 19 November 1726:[2]

— Weekly Journal, 19 November 1726

The “poor Woman”, Mary Toft, was twenty-four or twenty-five years old. She was baptised Mary Denyer on 21 February 1703, the daughter of John and Jane Denyer. In 1720 she married Joshua Toft, a journeyman clothier and together the couple had three children, Mary, Anne and James.[3][4] As an 18th-century English peasant, circumstances dictated that when in 1726 Mary again became pregnant, she continue working in the fields.[5] She complained of painful complications early in the pregnancy and in early August egested several pieces of flesh, one “as big as my arm”. This may have been the result of an abnormality of the developing placenta, which would have caused the embryo to stop developing and blood clots and flesh to be ejected.[6][7] Mary went into labour on 27 September. Her neighbour was called and watched as she produced several animal parts. This neighbour then showed the pieces to her mother and to her mother-in-law, Ann Toft, who by chance was a midwife. Ann Toft sent the flesh to John Howard, a Guildford-based man-midwife of thirty years’ experience.[6][8]

Initially, Howard dismissed the notion that Mary had given birth to animal parts, but the next day, despite his reservations, he went to see her. Ann Toft showed him more pieces of the previous night’s exertions, but on examining Mary, he found nothing. When Mary again went into labour, appearing to give birth to several more animal parts, Howard returned to continue his investigations. According to a contemporary account of 9 November, over the next few days he delivered “three legs of a Cat of a Tabby Colour, and one leg of a Rabbet: the guts were as a Cat’s and in them were three pieces of the Back-Bone of an Eel … The cat’s feet supposed were formed in her imagination from a cat she was fond of that slept on the bed at night.” Mary seemingly became ill once more and over the next few days delivered more pieces of rabbit.[6][7]

As the story became more widely known, on 4 November Henry Davenant, a member of the court of King George I, went to see for himself what was happening. He examined the samples Howard had collected and returned to London, ostensibly a believer. Howard had Mary moved to Guildford, where he offered to deliver rabbits in the presence of anyone who doubted her story.[9][10] Some of the letters he wrote to Davenant to notify him of any progress in the case came to the attention of Nathaniel St. André, since 1723 a Swiss surgeon to the Royal Household.[11] St. André would ultimately detail the contents of one of these letters in his pamphlet, “A short narrative of an extraordinary delivery of rabbets” (1727):[12]

— John Howard

Investigation

By the middle of November the British Royal Family were so interested in the story that they sent St. André and Samuel Molyneux, secretary to the Prince of Wales, to investigate. Apparently, they were not disappointed; arriving on 15 November they were taken by Howard to see Mary, who within hours delivered a rabbit’s torso.[13] St. André’s account details his examination of the rabbit. To check if it had breathed air, he placed a piece of its lung in water to see if it would float – which it did. St. André then performed a medical examination on Mary, and concluded that the rabbits were bred in her Fallopian tubes. In the doctors’ absence, Mary later that day reportedly delivered the torso of another rabbit, which the two also examined.[10][14] They returned that evening to find Mary again displaying violent contractions. A further medical examination followed, and St. André delivered some rabbit skin, followed a few minutes later by a rabbit’s head. Both men inspected the egested pieces of flesh, noting that some resembled the body parts of a cat.[15]

Fascinated, the King sent surgeon Cyriacus Ahlers to Guildford. Ahlers arrived on 20 November and found Mary exhibiting no signs of pregnancy. He may have already suspected the affair was a hoax, and observed that Mary seemed to press her knees and thighs together, as if to prevent something from “dropping down”. He thought Howard’s behaviour just as suspicious, as the man-midwife would not let him help deliver the rabbits – although Ahlers was not a man-midwife and in an earlier attempt had apparently put Mary through considerable pain.[16] Convinced the affair was a hoax, he lied, telling those involved that he believed Mary’s story, before making his excuses and returning to London, taking specimens of the rabbits with him. Upon closer study, he reportedly found evidence of them having been cut with a man-made instrument, and noted pieces of straw and grain in their droppings.[13][17]

On 21 November Ahlers reported his findings to the King and later to “several Persons of Note and Distinction”.[18] Howard wrote to Ahlers the next day, asking for the return of his specimens.[17] Ahlers’ suspicions began to worry both Howard and St. André, and apparently the king, as two days later St. André and a colleague were ordered back to Guildford.[16][19] Upon their arrival they met Howard, who told St. André that Mary had given birth to two more rabbits. She delivered several portions of what was presumed to be a placenta but she was by then quite ill, and suffering from a constant pain in the right side of her abdomen.[16][20] In a pre-emptive move against Ahlers, St. André collected affidavits from several witnesses, which in effect cast doubt on Ahlers’ honesty, and on 26 November gave an anatomical demonstration before the King to support Mary’s story.[19][21] According to his pamphlet, neither St. André nor Molyneux suspected any fraudulent activity.[22]

St. André was ordered by the King to travel back to Guildford and to bring Mary to London, so that further investigations could be carried out. He was accompanied by Richard Manningham, a well-known obstetrician who was knighted in 1721, and the second son of Thomas Manningham, Bishop of Chichester.[16] He examined Mary and found the right side of her abdomen slightly enlarged. Manningham also delivered what he thought was a hog’s bladder – although St. André and Howard disagreed with his identification – but became suspicious as it smelled of urine. Nevertheless, those involved agreed to say nothing in public and on their return to London on 29 November lodged Mary in Lacey’s Bagnio[a]A bagnio is a boarding house where rooms can be hired, or a brothel. in Leicester Fields.[19][23][24]

Examination

Printed in the early days of newspapers, the story became a national sensation, although some publications were sceptical; the Norwich Gazette viewed the affair simply as female gossip.[25] Rabbit stew and jugged hare disappeared from the dinner table, and as unlikely as the story sounded, many physicians felt compelled to see Mary for themselves. The political writer John Hervey later told his friend Henry Fox that:[3][26]

— John Hervey, 2nd Baron Hervey

Under St. André’s strict control, Mary was studied by a number of eminent physicians and surgeons, including John Maubray. In The Female Physician, Maubray had proposed that women could give birth to a creature he named a sooterkinImaginary kind of afterbirth in the form of an "evil-looking little animal" especially attributed to Dutch women.. He was a proponent of maternal impression, a widely held belief that conception and pregnancy could be influenced by what the mother dreamed, or saw,[27] and warned pregnant women that over-familiarity with household pets could cause their children to resemble those pets. He was reportedly happy to attend Mary, pleased that her case appeared to vindicate his theories,[28] but man-midwife James Douglas, like Manningham, presumed that the affair was a hoax and despite St. André’s repeated invitations, kept his distance. Douglas was one of the country’s most respected anatomists and a well-known man-midwife, whereas St. André was often considered to be a member of the court only because of his ability to speak the king’s native German.[29] St. André therefore desperately wanted the two to attend Mary; after George I’s accession to the throne the Whigs had become the dominant political faction, and Manningham and Douglas’s Whig affiliations and medical knowledge might have elevated his status as both doctor and philosopher.[24] Douglas thought that a woman giving birth to rabbits was as likely as a rabbit giving birth to a human child, but despite his scepticism he went to see her. When Manningham informed him of the suspected hog’s bladder, and after he examined Mary, he refused to engage St. André on the matter:[30]

— James Douglas

Under constant supervision, Mary went into labour several times, to no avail.[31]

Confession

The hoax was uncovered on 4 December. Thomas Onslow, 2nd Baron Onslow, had begun an investigation of his own and discovered that for the previous month Mary’s husband, Joshua, had been buying young rabbits. Convinced he had enough evidence to proceed, in a letter to physician Sir Hans Sloane he wrote that the affair had “almost alarmed England” and that he would soon publish his findings.[3][32] The same day, Thomas Howard, a porter at the bagnio, confessed to Justice of the Peace Sir Thomas Clarges that he had been bribed by Mary’s sister-in-law, Margaret, to sneak a rabbit into Mary’s chamber. When arrested and questioned Mary denied the accusation, while Margaret, under Douglas’s interrogation, claimed that she had obtained the rabbit for eating only.[33]

— Mary Toft

Manningham examined Mary and thought something remained in the cavity of her uterus, and so he successfully persuaded Clarges to allow her to remain at the bagnio.[33] Douglas, who had by then visited Mary, questioned her on three or four occasions, each time for several hours. After several days of this Manningham threatened to perform a painful operation on her, and on 7 December, in the presence of Manningham, Douglas, John Montagu and Frederick Calvert, Mary finally confessed.[3][33] Following her miscarriage and while her cervix permitted access, an accomplice had inserted into her womb the claws and body of a cat, and the head of a rabbit. They had also invented a story in which Mary claimed that during her pregnancy and while working in a field, she had been startled by a rabbit, and had since become obsessed with rabbits. For later parturitions, animal parts had been inserted into her vagina.[34][35]

Pressured again by Manningham and Douglas (it was the latter who took her confession), she made a further admission on 8 December and another on 9 December, before being sent to Tothill Fields Bridewell, charged on a statute of Edward III as a “vile cheat and imposter”.[31][36][37] In her earlier, unpublished confessions, she blamed the entire affair on a range of other participants, from her mother-in-law to John Howard. She also claimed that a travelling woman told her how to insert the rabbits into her body, and how such a scheme would ensure that she would “never want as long as I liv’d”. The British Journal reported that on 7 January 1727 she appeared at the Courts of Quarter Sessions at Westminster, charged “for being an abominable cheat and imposter in pretending to be delivered of several monstrous births”.[38] Margaret Toft had remained staunch, and refused to comment further. Mist’s Weekly Journal of 24 December 1726 reported that “the nurse has been examined as to the person’s concerned with her, but either was kept in the dark as to the imposition, or is not willing to disclose what she knows; for nothing can be got from her; so that her resolution shocks others.”[39]

Aftermath

Following the hoax, the medical profession’s gullibility became the target of a great deal of public mockery. William Hogarth published Cunicularii, or The Wise Men of Godliman in Consultation (1726), which portrays Mary in the throes of labour, surrounded by the tale’s chief participants. Figure “F” is Toft, “E” is her husband. “A” is St. André, and “D” is Howard.[40][41][42] In Dennis Todd’s Three Characters in Hogarth’s Cunicularii and Some Implications the author concludes that figure “G” is Mary Toft’s sister-in-law, Margaret Toft. Mary’s confession of 7 December demonstrates her insistence that her sister-in-law played no part in the hoax, but Manningham’s 1726 An Exact Diary of what was observ’d during a Close Attendance upon Mary Toft, the pretended Rabbet-Breeder of Godalming in Surrey offers eyewitness testimony of her complicity.[43] Hogarth’s print was not the only image that ridiculed the affair – George Vertue published The Surrey-Wonder, and The Doctors in Labour, or a New Wim-Wam in Guildford (12 plates), a broadsheet published in 1727 satirising St. André, was also popular at the time.[44]

The timing of Mary’s confession proved awkward for St. André, who on 3 December had published his forty-page pamphlet A Short Narrative of an Extraordinary Delivery of Rabbets.[42] On this document the surgeon had staked his reputation, and although it offers a more empirical account of the Toft case than earlier more fanciful publications about reproduction in general, ultimately it was derided.[45] Ahlers, his scepticism justified, published Some observations concerning the woman of Godlyman in Surrey, which details his account of events and his suspicion of the complicity of both St. André and Howard.[46]

St. André recanted his views on 9 December 1726. In 1729, following the death of Samuel Molyneux from poisoning, he married Molyneux’s widow, Elizabeth. This did little to impress his peers.[47] Molyneux’s cousin accused him of the poisoning, a charge that St. André defended by suing for defamation, but the careers of St. André and his wife were permanently damaged. Elizabeth lost her attendance on Queen Caroline, and St. André was publicly humiliated at court. Living on Elizabeth’s considerable wealth, they retired to the country, where St. André died in 1776, aged 96.[48][49] Manningham, desperate to exculpate himself, published a diary of his observations of Mary Toft, together with an account of her confession of the fraud, on 12 December. In it he suggested that Douglas had been fooled by Mary, and concerned with his image Douglas replied by publishing his own account.[37][50] Using the pseudonym “A Lover of Truth and Learning”, in 1727 Douglas also published The Sooterkin Dissected, in which he was scathingly critical of the sooterkin theory, calling it “a mere fiction of [Maubray’s] brain”.[51] The damage done to the medical profession was such that several doctors unconnected with the tale felt compelled to print statements that they had not believed Mary’s story.[42] On 7 January 1727 John Howard and Mary appeared before the bench, where Howard was fined £800, equivalent to about £117,000 as at 2018.[52][b]Using the Retail Price Index He returned to Surrey, where he continued to practise medicine until his death in 1755.[38][47][53]

Crowds reportedly mobbed Tothill Fields Bridewell for months, hoping to catch a glimpse of the now infamous Mary Toft. By this time she had become quite ill, and while incarcerated had her portrait drawn by John Laguerre. She was finally discharged on 8 April 1727, as it was unclear as to what charge should have been made against her.[54] The Toft family made no profit from the affair, and Mary returned to Surrey. In February 1728 (recorded as 1727 Old Style), she gave birth to a daughter, Elizabeth, noted in the Godalming parish register as her “first child after her pretended Rabett-breeding.”[55] Little is known of Mary’s later life. She briefly reappeared in 1740 when she was imprisoned for receiving stolen goods. She died in 1763, and her obituary ran in London newspapers alongside those of aristocrats.[53][55][56] She was buried in Godalming on 13 January 1763.[4]

Wikimedia Commons

The case was cited by opponents of Robert Walpole – generally regarded as the first de facto first British prime minister – of symbolising the age, which they perceived as greedy, corrupt and deceitful. One author, writing to the Prince of Wales’s mistress, suggested the story was a political portent of the approaching death of the prince’s father. On 7 January 1727 Mist’s Weekly Journal satirised the matter, making several allusions to political change, and comparing the affair to the events of 1641 when Parliament began its revolution against King Charles I.[58] The scandal provided the writers of Grub Street with enough material to produce pamphlets, squibs, broadsides and ballads for several months.[59] With publications such as St. André’s Miscarriage (1727) and The anatomist dissected: or the man-midwife finely brought to bed (1727) satirists scorned the objectivity of men-midwives, and critics of Mary’s attendants questioned their integrity, undermining their profession with sexual puns and allusions.[60]

Mary herself did not escape the ire of the satirists, who concentrated mainly on sexual innuendo. Some took advantage of a common 18th-century word for a rabbit track – prick – and others were scatological in nature. Much Ado about Nothing; or, A Plain Refutation of All that Has Been Written or Said Concerning the Rabbit-Woman of Godalming (1727) is one of the more cutting satires on Mary’s case. The document supposes to be the confession of ‘Merry Tuft’, “… in her own Stile and Spelling”. Poking fun at her illiteracy, it makes a number of obscene suggestions hinting at her promiscuity – “I wos a Wuman as had grate nattural parts, and a large Capassiti, and kapible of being kunserned in depe Kuntrivansis.”[61][62] The document also ridicules several of the physicians involved in the affair, and reflects the general view portrayed by the satirists that Mary was a weak woman and the least complicit of “the offenders” (regardless of her guilt). The notion contrasts with that expressed of her before the hoax was revealed and may indicate an overall strategy to disempower Mary completely. This is reflected in one of the most notable satires of the affair, Alexander Pope and William Pulteney’s anonymous satirical ballad The Discovery; or, The Squire Turn’d Ferret.[63] Published in 1726 and aimed at Samuel Molyneux, it rhymes “hare” with “hair”, and “coney” with “cunny”. The ballad opens with the following verse:[64]

Most true it is, I dare to say,

E'er since the Days of Eve,

The weakest Woman sometimes may

The wisest Man deceive.

Notes

| a | A bagnio is a boarding house where rooms can be hired, or a brothel. |

|---|---|

| b | Using the Retail Price Index |

References

- pp. 30–31

- pp. 118–119, 121

- p. 124

- p. 6

- p. 30

- p. 125

- p. 350

- p. 31

- p. 9

- pp. 5–6

- p. 27

- pp. 7–12

- pp. 12–14

- p. 352

- pp. 18–19

- p. 19

- p. 28

- pp. 28–30

- pp. 20–21

- p. 32

- p. 354

- p. 126

- p. 135

- pp. 127–128

- pp. 129–131

- p. 26

- p. 132

- p. 29

- pp. 199–200

- p. 355

- p. 7

- p. 34

- p. 356

- p. 168

- p. 168

- pp. 28–29

- p. 30

- p. 32

- p. 45

- pp. 126–127

- pp. 1–23

- p. 132

- pp. 142–143

- p. 11

- p. 43

- p. 130

- p. 141

- pp. 131–132

- p. 143

- p. 131

- p. 134

- pp. 132–134

- pp. 33–34

- pp. 12–17

- pp. 69–72