Wikimedia Commons

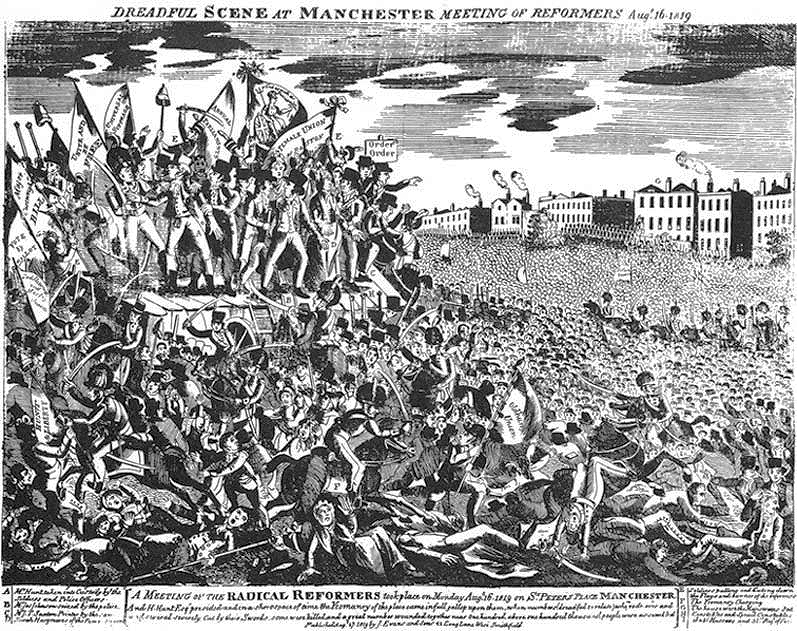

The Peterloo Massacre (or Battle of Peterloo) occurred at St Peter’s Field, Manchester, England, on 16 August 1819, when cavalry charged into a crowd of 60,000–80,000 that had gathered to demand the reform of parliamentary representation.

The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 had resulted in periods of famine and chronic unemployment, exacerbated by the introduction of the first of the Corn Laws. By the beginning of 1819 the pressure generated by poor economic conditions, coupled with the relative lack of suffrage in Northern England, had enhanced the appeal of political radicalism. In response, the Manchester Patriotic Union, a group agitating for parliamentary reform, organised a demonstration to be addressed by the well-known radical orator Henry Hunt.

Shortly after the meeting began local magistrates called on the military authorities to arrest Hunt and several others on the hustings with him, and to disperse the crowd. Cavalry charged into the crowd with sabres drawn, and in the ensuing confusion, 15 people were killed and 400–700 were injured. The massacre was given the name Peterloo in an ironic comparison to the Battle of Waterloo, which had taken place four years earlier.

Historian Robert Poole has called the Peterloo Massacre one of the defining moments of its age. In its own time, the London and national papers shared the horror felt in the Manchester region, but Peterloo’s immediate effect was to cause the government to crack down on reform, with the passing of what became known as the Six ActsSix Acts of Parliament introduced in the aftermath of the 1819 Peterloo Massacre, intended to quash any further protests in support of parliamentary reform. Six Acts of Parliament introduced in the aftermath of the 1819 Peterloo Massacre, intended to quash any further protests in support of parliamentary reform. . It also led directly to the foundation of The Manchester Guardian (now The Guardian), but had little other effect on the pace of reform. In a survey conducted by The Guardian in 2006, Peterloo came second to the Putney Debates as the event from British history that most deserved a proper monument or a memorial. Peterloo is commemorated by a plaque close to the site, a replacement for an earlier one that was criticised as being inadequate as it did not reflect the scale of the massacre.

Background

Suffrage

In 1819, Lancashire was represented by two Members of Parliament (MPs). Voting was restricted to the adult male owners of freehold land with an annual rental value of 40 shillings or more – the equivalent of about £150 in 2018[a]Using the retail price index[1] – and votes could only be cast at the county town of Lancaster, by a public spoken declaration at the hustings. Constituency boundaries were out of date, and the so-called “rotten boroughs” had a hugely disproportionate influence on the membership of the Parliament of the United Kingdom compared to the size of their populations: Old Sarum in Wiltshire, with one voter, elected two MPs,[2] as did Dunwich in Suffolk, which by the early 19th century had almost completely disappeared into the sea.[3] The major urban centres of Manchester, Salford, Bolton, Blackburn, Rochdale, Ashton-under-Lyne, Oldham and Stockport, with a combined population of almost one million, were represented by either the two county MPs for Lancashire, or the two for Cheshire in the case of Stockport. By comparison, more than half of all MPs were elected by a total of just 154 voters.[2] These inequalities in political representation led to calls for reform.

Economic conditions

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, a brief boom in textile manufacture was followed by periods of chronic economic depression, particularly among textile weavers and spinners (the textile trade was concentrated in Lancashire).[4] Weavers who could have expected to earn 15 shillings for a six-day week in 1803, saw their wages cut to 5 shillings or even 4s 6d by 1818. The industrialists, who were cutting wages without offering relief, blamed market forces generated by the aftershocks of the Napoleonic Wars.[5] Exacerbating matters were the Corn Laws, the first of which was passed in 1815, imposing a tariff on foreign grain in an effort to protect English grain producers. The cost of food rose as people were forced to buy the more expensive and lower quality British grain, and periods of famine and chronic unemployment ensued, increasing the desire for political reform both in Lancashire and in the country at large.[6][7]

Radical mass meetings

Economic conditions in 1817 led to a group who became known as Blanketeers to organise a march from Manchester to London so they could petition the Prince Regent for parliamentary reform.[8] A crowd of 25,000 including 5,000 men who intended to march gathered in St Peter’s Fields. After the magistrates read the Riot Act, the crowd was dispersed by the King’s Dragoon Guards. The ringleaders were arrested and subsequently released when serious charges against them were not forthcoming. In April 1819 three leading Blanketeers were convicted of sedition and conspiracy when witnesses alleged they had advocated the principal towns of the kingdom should elect representatives to a National Convention to demand their rights and if refused enforce them ‘sword in hand’ during a meeting in Stockport in September 1818.[9]

By the beginning of 1819 pressure generated by poor economic conditions was at its peak and had enhanced the appeal of political radicalism among the cotton loom weavers of south Lancashire.[4] In January 1819, a crowd of about 10,000 gathered at St Peter’s Fields to hear the radical orator Henry Hunt and called on the Prince Regent to choose ministers who would repeal the Corn Laws. The meeting, conducted in the presence of the cavalry, passed off without incident.[10]

In July 1819, the town’s magistrates wrote to Lord Sidmouth warning they thought a “general rising” was imminent, the “deep distress of the manufacturing classes” was being worked on by the “unbounded liberty of the press” and “the harangues of a few desperate demagogues” at weekly meetings. “Possessing no power to prevent the meetings” the magistrates admitted they were at a loss as to how to stem the doctrines being disseminated.[11]

August meeting

Against this background, a “great assembly” was organised by the Manchester Patriotic Union formed by radicals from the Manchester Observer. The newspaper’s founder Joseph Johnson was the union’s secretary. He wrote to Henry Hunt asking him to chair a meeting in Manchester on 2 August 1819. Johnson wrote:

Unknown to Johnson and Hunt, the letter was intercepted by government spies and copied before being sent to its destination. The contents were interpreted to mean that an insurrection was being planned, and the government responded by ordering the 15th Hussars to Manchester.[13]

Wikimedia Commons

The mass public meeting planned for 2 August was delayed until 9 August. The Manchester Observer reported it was called “to take into consideration the most speedy and effectual mode of obtaining Radical reform in the Common House of Parliament” and “to consider the propriety of the ‘Unrepresented Inhabitants of Manchester’ electing a person to represent them in Parliament”.[14] The magistrates, led by William Hulton, had been advised by the acting Home Secretary, Henry Hobhouse, that “the election of a member of parliament without the King’s writ” was a serious misdemeanour,[15] encouraging them to declare the assembly illegal as soon as it was announced on 31 July.[16][17] The radicals sought a second opinion on the meeting’s legality which was that “The intention of choosing Representatives, contrary to the existing law, tends greatly to render the proposed Meeting seditious; under those circumstances it would be deemed justifiable in the Magistrates to prevent such Meeting”.[18]

On 3 August, Hobhouse conveyed the view of the Attorney-General that the magistrates were incorrect to declare 9 August meeting illegal as it was called to consider the election of a representative,[19] and it was not the intention to elect an MP that was illegal, but the execution of that intention.[20] On 4 August Hobhouse advised against any attempt to forcibly prevent the 9 August meeting if it went ahead, or do anything beyond collecting evidence for subsequent prosecution unless the meeting got out of hand:

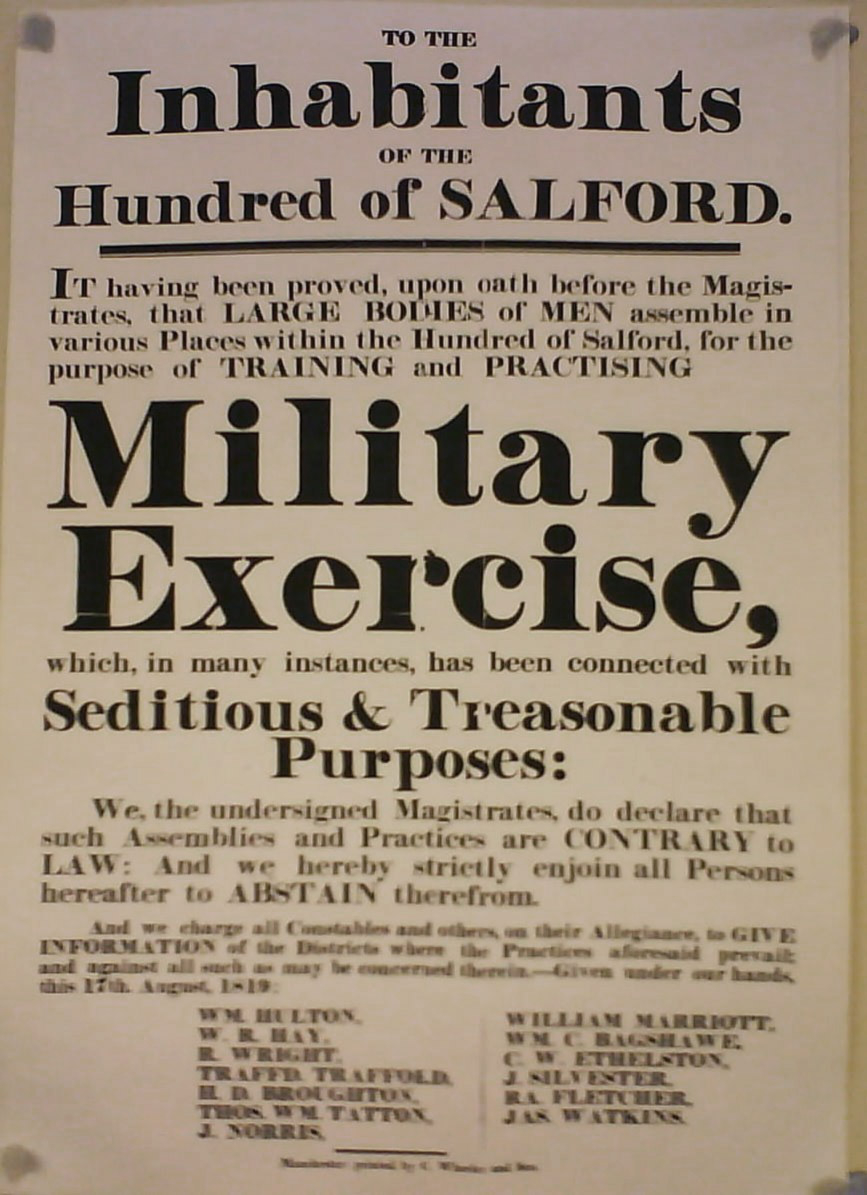

The meeting on 9 August was postponed after magistrates banned it to discourage the radicals but Hunt and his followers were determined to assemble and a meeting was organised for 16 August, with its declared aim solely “to consider the propriety of adopting the most LEGAL and EFFECTUAL means of obtaining a reform in the Common House of Parliament”.[18] The press had mocked earlier meetings of working men because of their ragged, dirty appearance and disorganised conduct, but the organisers were determined that those attending the St Peter’s Field meeting would be neatly turned out and march to the event in good order.[22] Samuel Bamford, a local radical who led the Middleton contingent, wrote that “It was deemed expedient that this meeting should be as morally effective as possible, and, that it should exhibit a spectacle such as had never before been witnessed in England.”[4] Instructions were given to the various committees forming the contingents that “Cleanliness, Sobriety, Order and Peace” and a “prohibition of all weapons of offence or defence” were to be observed throughout the demonstration.[23] Each contingent was drilled and rehearsed in the fields of the townshipsDivision of an ecclesiastical parish that had civil functions. around Manchester adding to the concerns of the authorities.[17] A royal proclamation forbidding the practice of drilling had been posted in Manchester on 3 August,[20] but on 9 August an informant reported to Rochdale magistrates that at Tandle Hill the previous day, 700 men were “drilling in companies” and “going through the usual evolutions of a regiment” and an onlooker had said the men “were fit to contend with any regular troops, only they wanted arms”.[24]

Rehearsals

Although banning the 9 August meeting had been intended to discourage the radicals entirely, Hunt and his followers were determined to assemble. A new meeting was organised for 16 August,[25] after the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth, had written to the magistrates instructing them that it was not the intention to elect an MP that was illegal, but the execution of that intention.[20]

The press had frequently mocked previous meetings of working men because of their ragged, dirty appearance and disorganised conduct. The organisers were determined that those attending the meeting at St Peter’s Field would be neatly turned out and would march to the event in good order.[22] Samuel Bamford, a local radical who led the Middleton contingent to the assembly, wrote that “It was deemed expedient that this meeting should be as morally effective as possible, and, that it should exhibit a spectacle such as had never before been witnessed in England.”[4] Instructions were given to the various committees forming the contingents that “Cleanliness, Sobriety, Order and Peace” and a “prohibition of all weapons of offence or defence” were to be observed throughout the demonstration.[23] Each contingent was drilled and rehearsed in the fields of the townships around Manchester, further adding to the concerns of the authorities.[25] One spy reported that “seven hundred men drilled at Tandle Hill as well as any army regiment would”.[25] A royal proclamation forbidding the practice of drilling was posted in Manchester on 3 August.[20]

Assembly

sent to St Peter’s Field

Wikimedia Commons

St Peter’s Field was a croft (an open piece of land) alongside Mount Street which was being cleared to enable the last section of Peter Street to be constructed. Piles of brushwood had been placed at the end of the field nearest to the Friends Meeting House, but the remainder of the field was clear.[26] Thomas Worrell, Manchester’s Assistant Surveyor of Paving, arrived to inspect the field at 7:00 am. His job was to remove anything that might be used as a weapon, and he duly had “about a quarter of a load” of stones carted away.[27]

Monday, 16 August 1819, was a hot summer’s day, with a cloudless blue sky. The fine weather almost certainly increased the size of the crowd significantly; marching from the outer townships in the cold and rain would have been a much less attractive prospect.[28]

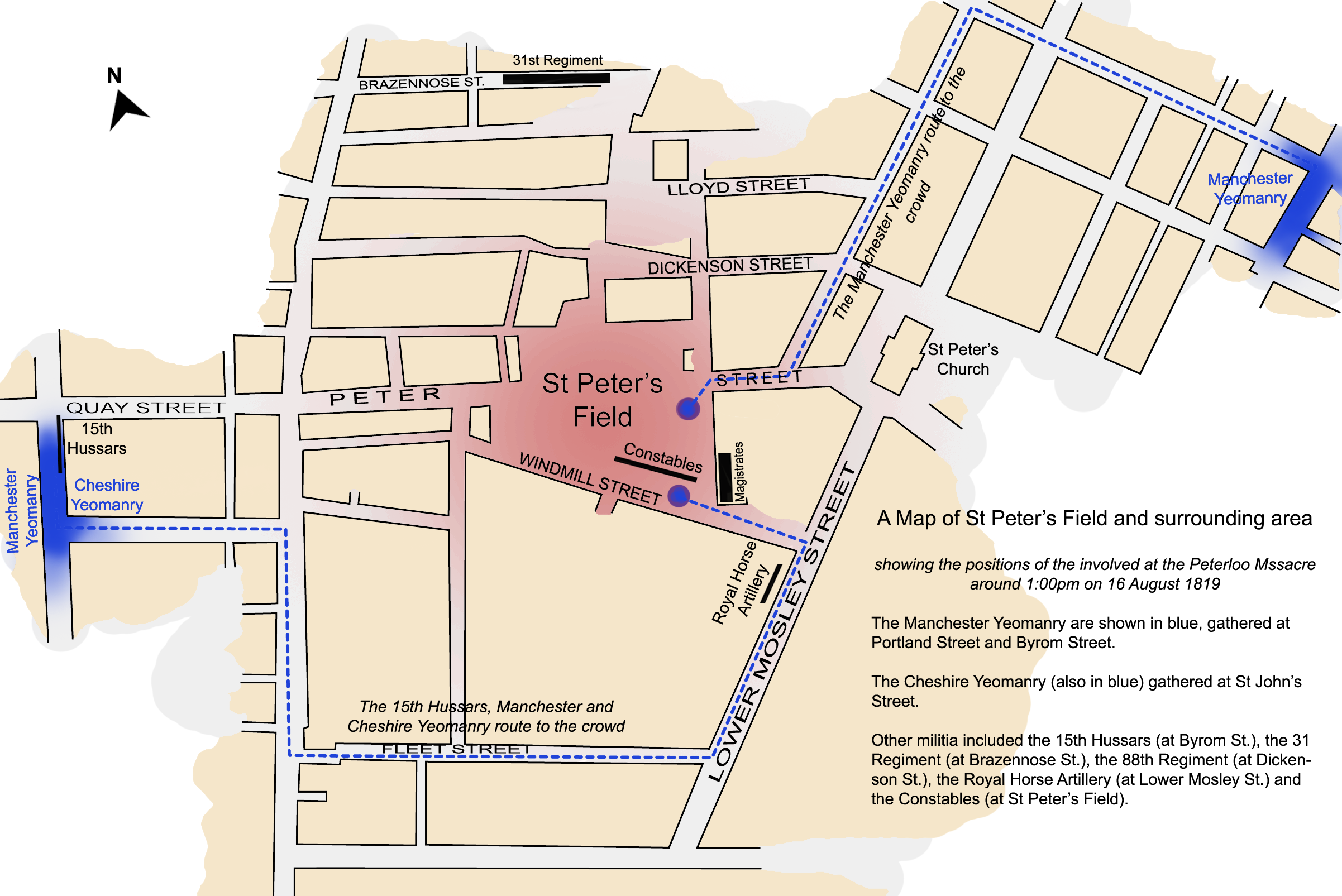

The Manchester magistrates met at 9:00 am, to breakfast at the Star Inn on Deansgate and to consider what action they should take on Henry Hunt’s arrival at the meeting. By 10:30 am they had come to no conclusions, and moved to a house on the southeastern corner of St Peter’s Field, from where they planned to observe the meeting.[29] They were concerned that it would end in a riot, or even a rebellion, and had arranged for a substantial number of regular troops and militia yeomanry to be deployed. The military presence comprised 600 men of the 15th Hussars; several hundred infantrymen; a Royal Horse Artillery unit with two six-pounder (2.7 kg) guns; 400 men of the Cheshire Yeomanry; 400 special constables; and 120 cavalry of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, relatively inexperienced militia recruited from among local shopkeepers and tradesmen, the most numerous of which were publicans.[30] The Yeomanry were variously described as “younger members of the Tory party in arms”,[31] and as “hot-headed young men, who had volunteered into that service from their intense hatred of Radicalism”.[32] Socialist writer Mark Krantz has described them as “the local business mafia on horseback”.[33]

The British Army in the north was under the overall command of General Sir John Byng. When he had initially learned that the meeting was scheduled for 2 August he had written to the Home Office stating that he hoped the Manchester magistrates would show firmness on the day:

The revised meeting date of 16 August, however, coincided with the horse races at York, a fashionable event at which Byng had entries in two races. He once again wrote to the Home Office, saying that although he would still be prepared to be in command in Manchester on the day of the meeting if it was thought really necessary, he had absolute confidence in his deputy commander, Lieutenant Colonel Guy L’Estrange.[35]

Meeting

The crowd that gathered in St Peter’s Field arrived in disciplined and organised contingents. Each village or chapelryChurch subordinate to a parish church serving an area known as a chapelry, for the convenience of those parishioners who would find it difficult to attend services at the parish church. was given a time and a place to meet, from where its members were to proceed to assembly points in the larger towns or townships, and from there on to Manchester.[36] Contingents were sent from all around the region, the largest and “best dressed”[37] of which was a group of 10,000 who had travelled from Oldham Green, comprising people from Oldham, Royton (which included a sizable female section), Crompton, Lees, Saddleworth and Mossley.[37] Other sizable contingents marched from Middleton and Rochdale (6,000 strong) and Stockport (1,500–5,000 strong).[38] Reports of the size of the crowd at the meeting vary substantially. Contemporaries estimated it from 30,000 to as many as 150,000; modern estimates are 60,000–80,000.[39] Scholar Joyce Marlow describes the event as “The most numerous meeting that ever took place in Great Britain” and elaborates that the generally accepted figure of 60,000 would have been 6 per cent of the population of Lancashire, or half the population of the immediate area around Manchester.[37]

The assembly was intended by its organisers and participants to be a peaceful meeting; Henry Hunt had exhorted everyone attending to come “armed with no other weapon but that of a self-approving conscience”,[40] and many were wearing their “Sunday best” clothes.[26] Samuel Bamford recounts the following incident, which occurred as the Middleton contingent reached the outskirts of Manchester:

Although some observers, including the Rev. W. R. Hay, chairman of the Salford Quarter Sessions, claimed that “The active part of the meeting may be said to have come in wholly from the country”,[42] others such as John Shuttleworth, a local cotton manufacturer, estimated that most were from Manchester, a view that would subsequently be supported by the casualty lists. Of the casualties whose residence was recorded, 61% lived within a three-mile radius of the centre of Manchester.[43] Some groups carried banners with texts like “No Corn Laws”, “Annual Parliaments”, “Universal suffrage” and “Vote By Ballot”. The only banner known to have survived is in Middleton Public Library. It was carried by Thomas Redford, who was injured by a yeomanry sabre. Made of green silk embossed with gold lettering, one side of the banner is inscribed “Liberty and Fraternity” and the other “Unity and Strength”.[44]

At about noon, several hundred special constables were led onto the field. They formed two lines in the crowd a few yards apart, in an attempt to form a corridor through the crowd between the house where the magistrates were watching and the hustings, two waggons lashed together. Believing that this might be intended as the route by which the magistrates would later send their representatives to arrest the speakers, some members of the crowd pushed the waggons away from the constables, and pressed around the hustings to form a human barrier.[45]

Hunt’s carriage arrived at the meeting shortly after 1:00 pm, and he made his way to the hustings. Alongside Hunt on the speakers’ stand were John Knight, a cotton manufacturer and reformer, Joseph Johnson, the organiser of the meeting, John Thacker Saxton, managing editor of the Manchester Observer, the publisher Richard Carlile, and George Swift, reformer and shoemaker. There were also a number of reporters, including John Tyas of The Times, John Smith of the Liverpool Echo and Edward Baines Jr, the son of the editor of the Leeds Mercury.[46] By this time St Peter’s Field, an area of three acres (1 ha), was packed with tens of thousands of men, women and children. The crowd around the speakers was so dense that “their hats seemed to touch”; large groups of curious spectators gathered on the outskirts of the crowd. The rest of Manchester was like a ghost town, the streets and shops were empty.[47]

Cavalry charge

When I wrote these two letters, I considered at that moment that the lives and properties of all the persons in Manchester were in the greatest possible danger.[48] When I wrote these two letters, I considered at that moment that the lives and properties of all the persons in Manchester were in the greatest possible danger.[48]— William Hulton |

William HultonLandowner who lived at Hulton Hall in Lancashire, notorious for his part in the Peterloo Massacre. , the chairman of the magistrates watching from the house on the edge of St Peter’s Field, saw the enthusiastic reception that Hunt received on his arrival at the assembly, and it encouraged him to action. He issued an arrest warrant for Henry Hunt, Joseph Johnson, John Knight, and James Moorhouse. On being handed the warrant the Chief Constable, Jonathan Andrews, offered his opinion that the press of the crowd surrounding the hustings would make military assistance necessary for its execution. Hulton then wrote two letters, one to Major Thomas Trafford, the commanding officer of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry, and the other to the overall military commander in Manchester, Lieutenant Colonel Guy L’Estrange. The contents of both notes were similar:[49]

— Letter sent by William Hulton to Major Trafford of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry

The notes were handed to two horsemen who were standing by. The Manchester and Salford Yeomanry were stationed just a short distance away in Portland Street, and so received their note first. They immediately drew their swords and galloped towards St Peter’s Field. One trooper, in a frantic attempt to catch up, knocked down a woman in Cooper Street, causing the death of her child when he was thrown from her arms;[50] two-year-old William Fildes was the first casualty of Peterloo.[51]

Sixty cavalrymen of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, led by Captain Hugh Hornby Birley, a local factory owner, arrived at the house from where the magistrates were watching; some reports allege that they were drunk.[52] Andrews, the Chief Constable, instructed Birley that he had an arrest warrant which he needed assistance to execute. Birley was asked to take his cavalry to the hustings to allow the speakers to be removed; it was by then about 1:40 pm.[53]

The route towards the hustings between the special constables was narrow, and as the inexperienced horses were thrust further and further into the crowd they reared and plunged as people tried to get out of their way.[50] The arrest warrant had been given to the Deputy Constable, Joseph Nadin, who followed behind the yeomanry. As the cavalry pushed towards the speakers’ stand they became stuck in the crowd, and in panic started to hack about them with their sabres.[54] On his arrival at the stand Nadin arrested Hunt, Johnson and a number of others including John Tyas, the reporter from The Times.[55] According to Tyas the yeomanry’s progress through the crowd had provoked a hail of bricks and stones, and caused them to lose “all command of temper”.[56] Their mission to execute the arrest warrant having been achieved, they then set about destroying the banners and flags carried by the crowd.[56]

From his vantage point William Hulton perceived the unfolding events as an assault on the yeomanry, and on L’Estrange’s arrival at 1:50 pm, at the head of his hussars, he ordered them into the field to disperse the crowd with the words: “Good God, Sir, don’t you see they are attacking the Yeomanry; disperse the meeting!”[57] The 15th Hussars formed themselves into a line stretching across the eastern end of St Peter’s Field, and charged into the crowd. At about the same time the Cheshire Yeomanry charged from the southern edge of the field.[58] At first the crowd had some difficulty in dispersing, as the main exit route into Peter Street was blocked by the 88th Regiment of Foot, standing with bayonets fixed. One officer of the 15th Hussars was heard trying to restrain the by now out of control Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, who were “cutting at every one they could reach”: “For shame! For shame! Gentlemen: forbear, forbear! The people cannot get away!”[59]

However, within ten minutes the crowd had been dispersed, at the cost of 11 dead and more than 600 injured. Only the wounded, their helpers, and the dead were left behind. A woman living nearby said she saw “a very great deal of blood”.[25] For some time afterwards there was rioting in the streets, most seriously at New Cross, where troops fired on a crowd attacking a shop belonging to someone rumoured to have taken one of the women reformers’ flags as a souvenir. Peace was not restored in Manchester until the next morning, and in Stockport and Macclesfield rioting continued on the 17th.[60] There was also a major riot in Oldham that day, during which one person was shot and wounded.[25]

Victims

Wikimedia Commons

The exact number of those killed and injured at Peterloo has never been established with certainty.[61] Sources claim 11–15 killed and 400–700 injured. The Manchester Relief Committee, a body set up to provide relief for the victims of Peterloo, gave the number of injured as 420, while Radical sources listed 500.[61] The true number is difficult to estimate, as many of the wounded hid their injuries for fear of retribution by the authorities.[62] Three of William Marsh’s six children who worked in the factory belonging to Captain Hugh Birley of the Manchester Yeomanry lost their jobs because their father had attended the meeting.[63] James Lees was admitted to Manchester Infirmary with two severe sabre wounds to the head, but was refused treatment and sent home after refusing to agree with the surgeon’s insistence that “he had had enough of Manchester meetings”.[63]

A particular feature of the meeting at Peterloo was the number of women present. Female reform societies had been formed in North West England during June and July 1819, the first in Britain. Many of the women were dressed distinctively in white, and some formed all-female contingents, carrying their own flags.[64] Of the 654 recorded casualties, at least 168 were women, four of whom died either at St Peter’s Field or later as a result of their wounds. It has been estimated that less than 12 per cent of the crowd was made up of females, suggesting that women were at significantly greater risk of injury than men by a factor of almost 3:1. Richard Carlile claimed that the women were especially targeted, a view apparently supported by the large number who suffered from wounds caused by weapons.[65]

Eleven of the fatalities listed occurred on St Peter’s Field. Others, such as John Lees of Oldham, died later of their wounds, and some like Joshua Whitworth were killed in the rioting that followed the crowd’s dispersal from the field.

| Name | Abode | Died | Cause | Notes | Refs. |

| John Ashton | Cowhill, Chadderton | 16 August | Sabred and trampled on by the crowd | Carried the black flag of the Saddleworth, Lees and Mossley Union, inscribed “Taxation without representation is unjust and tyrannical. NO CORN LAWS”. The inquest jury returned a verdict of accidental death. His son, Samuel, received 20 shillings in relief. | [66][67] |

| John Ashworth | Bulls Head, Manchester | Sabred and trampled | Ashworth was a Special Constable, presumably attacked unintentionally by the cavalry. | [66] | |

| William Bradshaw | Lily-hill, Bury | Shot by musket | [66][68] | ||

| Thomas Buckley | Baretrees, Chadderton | Sabred and stabbed by bayonet | [66][69] | ||

| Robert Campbell | Miller Street, Salford | 18 August | Killed by a mob in Newton Lane | Campbell was a Special Constable | [70] |

| James Crompton | Barton-upon-Irwell | Trampled by the cavalry | Buried on 1 September | [66][71] | |

| Edmund Dawson | Saddleworth | Died of sabre wounds at the Manchester Royal Infirmary | The historian Joyce Marlow has suggested that Edmund and William Dawson may have been the same individual. | [66] | |

| William Dawson | Saddleworth | Sabred, crushed and killed on the spot | [66] | ||

| Margaret Downes | Manchester | Sabred | [72] | ||

| William Evans | Hulme | Trampled by cavalry | Evans was a Special Constable | [73] | |

| William Fildes | Kennedy Street, Manchester | Ridden over by cavalry | Two years old, he was first victim of the massacre. His mother was carrying him across the road when she was struck by a trooper of the Manchester Yeomanry, galloping towards St Peters Field. | [66] | |

| Mary Heys | Oxford Road, Manchester | 17 December | Ridden over by cavalry | Mother of six children, and pregnant at the time of the meeting. Disabled and suffering from almost daily fits following her injuries, the premature birth of her seven-month-old child resulted in her death. | [66][74] |

| Sarah Jones | 96 Silk Street, Salford | No cause given by Marlow but listed as “bruised in the head” by Frow | Mother of seven children. Beaten on the head by a Special Constable’s truncheon. | [66][75][b]Frow (1984), p. 8 lists Sarah as injured, not that she died. | |

| John Lees | Oldham | 9 September | Sabred | Lees was an ex-soldier who had fought in the Battle of Waterloo. | [66] |

| Arthur Neil | Pidgeon Street, Manchester | Inwardly crushed | [66] | ||

| Martha Partington | Eccles | Thrown into a cellar and killed on the spot | [66] | ||

| John Rhodes | Pits, Hopwood | 18 or 19 November | Sabre wound to the head | Rhodes’ body was dissected by order of magistrates who wished to prove that his death was not a result of Peterloo. The coroner’s inquest found that he had died from natural causes. | [66][76] |

| Joshua Whitworth | 20 August | Shot at New Cross | [66] |

Reaction and aftermath

Public

The Peterloo Massacre has been called one of the defining moments of its age.[77] Many of those present, including local masters, employers and owners, were horrified by the carnage. One of the casualties, Oldham cloth-worker and ex-soldier John Lees, who died from his wounds on 7 September, had been present at the Battle of Waterloo.[25] Shortly before his death he said to a friend that he had never been in such danger as at Peterloo: “At Waterloo there was man to man but there it was downright murder.”[78] When news of the massacre began to spread, the population of Manchester and surrounding districts were horrified and outraged.[79]

As the ‘Peterloo Massacre’ cannot be otherwise than grossly libellous you will probably deem it right to proceed by arresting the publishers.[80] As the ‘Peterloo Massacre’ cannot be otherwise than grossly libellous you will probably deem it right to proceed by arresting the publishers.[80]— Letter from the Home Office to Magistrate Norris, 25 August 1819 |

Publications

This was the first public meeting at which journalists from a number of important distant newspapers were present, and within a day or so of the event accounts were published as far away as London, Leeds and Liverpool.[50] The London and national papers shared the horror felt in the Manchester region, and the feeling of indignation throughout the country became intense.

James Wroe as editor of the Manchester Observer was the first journalist to describe the incident as the “Peterloo Massacre”, coining his headline by combining the name of the meeting place, St Peter’s Field, with the Battle of Waterloo that had taken place only four years before.[81] Wroe subsequently wrote pamphlets entitled “The Peterloo Massacre: A Faithful Narrative of the Events”. Priced at 2d each, they sold out each print run for 14 weeks, having a large national circulation.[81] Sir Francis Burdett, a reformist MP, was jailed for three months for his publication of a seditious libel, so moved was he.

| PETER LOO MASSACRE ! ! ! Just published No. 1 price twopence of PETER LOO MASSACRE Containing a full, true and faithful account of the inhuman murders, woundings and other monstous Cruelties exercised by a set of INFERNALS (miscalled Soldiers) upon unarmed and distressed People.[80] — Manchester Observer, 28 August 1819 |

The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley was living in Italy at the time and did not hear of the massacre until 5 September. He immediately wrote a poem, “The Masque of Anarchy”, subtitled “Written on the Occasion of the Massacre at Manchester”, and sent it for publication in the radical periodical The Examiner. But owing to restrictions on the radical press the poem was not published until 1832.[82] Many commemorative items such as plates, jugs, handkerchiefs and medals were produced, all with the iconic image of Peterloo; cavalrymen with swords drawn riding down and slashing at defenceless civilians.[83]

Political

The government instructed the police and courts to go after the journalists, presses and publication that was the Manchester Observer.[81] Wroe was arrested and charged with producing a seditious publication. Found guilty he was sentenced to twelve months in prison, plus a £100 fine.[81] Outstanding libelous court cases against the Manchester Observer were suddenly rushed through the courts, and even a continual change of sub-editors was not sufficient a defence against a series of police raids, often just on the suspicion of the newspaper writing a radical article. The result was that the Manchester Observer was almost continually shutdown from late 1819 onwards, finally closing in February 1820 where it recommended in editorial that readers now follow events via the newly formed Manchester Guardian.[81]

Hunt and eight others were tried at York Assizes on 16 March 1820, charged with sedition. After a two-week trial, five of the ten defendants were found guilty. Hunt was sentenced to 30 months in Ilchester Gaol; Bamford, Johnson, and Healey were given one year each, and Knight was jailed for two years on a subsequent charge. A test case was brought against four members of the Manchester Yeomanry at Lancaster Assizes, on 4 April 1822: Captain Birley, Captain Withington, Trumpeter Meagher, and Private Oliver. All were acquitted, as the court ruled that their actions had been justified to disperse an illegal gathering.[84]

Wikimedia Commons

The government declared its support for the actions taken by the magistrates and the army. The Manchester magistrates held a supposedly public meeting on 19 August, so that resolutions supporting the action they had taken three days before could be published. Cotton merchants Archibald Prentice (later editor of The Manchester Times) and Absalom Watkin (a later corn-law reformer), both members of the Little Circle, organised a petition of protest against the violence at St Peter’s Field and the validity of the magistrate’s meeting. Within a few days it had collected 4800 signatures.[85] Nevertheless the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth, on 27 August conveyed to the magistrates the thanks of the Prince Regent for their action in the “preservation of the public peace”.[6] That public exoneration was met with fierce anger and criticism. During a debate at Hopkins Street Robert Wedderburn declared “The Prince is a fool with his Wonderful letters of thanks … What is the Prince Regent or King to us, we want no King – he is no use to us.”[86] In an open letter, Richard Carlile said:

Unless the Prince calls his ministers to account and relieved his people, he would surely be deposed and make them all REPUBLICANS, despite all adherence to ancient and established institutions.[86]

For a few months following Peterloo it seemed to the authorities that the country was heading towards an armed rebellion. Encouraging them in that belief were two abortive uprisings, in Huddersfield and Burnley, during the autumn of 1819, and the discovery and foiling of the Cato Street Conspiracy to blow up the cabinet that winter.[87] By the end of the year, the government had introduced legislation, later known as the Six ActsSix Acts of Parliament introduced in the aftermath of the 1819 Peterloo Massacre, intended to quash any further protests in support of parliamentary reform. Six Acts of Parliament introduced in the aftermath of the 1819 Peterloo Massacre, intended to quash any further protests in support of parliamentary reform. , to suppress radical meetings and publications, and by the end of 1820 every significant working-class radical reformer was in jail; civil liberties had declined to an even lower level than they were before Peterloo. The historian Robert Reid has written that “it is not fanciful to compare the restricted freedoms of the British worker in the post-Peterloo period in the early nineteenth century with those of the black South African in the post-Sharpeville period of the late twentieth century”.[88]

One direct consequence of Peterloo was the foundation of the Manchester Guardian newspaper in 1821, by the Little Circle group of non-conformist Manchester businessmen headed by John Edward Taylor, a witness to the massacre.[31] The prospectus announcing the new publication proclaimed that it would “zealously enforce the principles of civil and religious Liberty … warmly advocate the cause of Reform … endeavour to assist in the diffusion of just principles of Political Economy and … support, without reference to the party from which they emanate, all serviceable measures”.[89]

Events such as the Pentridge Rising, the March of the Blanketeers and the Spa Fields meeting, all serve to indicate the breadth, diversity and widespread geographical scale of the demand for economic and political reform at the time.[90] Peterloo had no effect on the speed of reform, but in due course all but one of the reformers’ demands, annual parliaments, were met.[91] Following the Great Reform Act of 1832, the newly created Manchester parliamentary borough elected its first two MPs. Five candidates including William Cobbett stood, and the Whigs, Charles Poulett Thomson and Mark Philips, were elected.[92] Manchester became a Municipal Borough in 1837, and what remained of the manorial rights were subsequently purchased by the borough council.

Commemoration

| |

Original blue plaque commemorating the Peterloo Massacre Wikimedia Commons | The replacement red plaque, unveiled by the Lord Mayor of Manchester on 10 December 2007 Wikimedia Commons |

The Skelmanthorpe FlagBanner made in honour of the victims of the Peterloo Massacre. is believed to have been made in Skelmanthorpe, in the West Riding of Yorkshire in 1819, in part to honour the victims of the Peterloo Massacre.[93]

The Free Trade Hall, home of the Anti-Corn Law League, was built partly as a “cenotaph raised on the shades of the victims” of Peterloo.[94] Until 2007 the massacre was commemorated by a blue plaque on the wall of the present building, the third to occupy the site, now the Radisson Hotel. It was regarded as a less than appropriate memorial because it under reported the incident as a dispersal, and the deaths were omitted completely.[31] In a 2006 survey conducted by The Guardian, Peterloo came second to St. Mary’s Church, Putney, the venue for the Putney Debates, as the event from British history that most deserved a proper monument.[95] A Peterloo Massacre Memorial Campaign was set up to lobby for a more appropriate monument to an event that has been described as Manchester’s Tiananmen Square.[96]

In 2007, Manchester City Council replaced the original blue plaque with a red one, giving a fuller account of the events of 1819. It was unveiled on 10 December 2007 by the Lord Mayor of Manchester, Councillor Glynn Evans.[97] Under the heading “St. Peter’s Fields: The Peterloo Massacre”, the new plaque reads:

In 1968, in celebration of its centenary, the Trades Union Congress commissioned British composer Sir Malcolm Arnold to write the Peterloo Overture.[99] Other 20th-century musical commemorations include “Ned Ludd Part 5” on electric folk group Steeleye Span’s 2006 album Bloody Men, and Rochdale rock band Tractor’s suite of five songs written and recorded in 1973, later included on their 1992 release Worst Enemies.

Mike Leigh’s feature-length film about the events of 1819, Peterloo, premiered in Manchester on 17 October 2018 as part of the London Film Festival.[c]Mike Leigh was born in nearby Salford. The actors Maxine Peake and Roy Kinnear appear in the film.[100]

Notes

| a | Using the retail price index[1] |

|---|---|

| b | Frow (1984), p. 8 lists Sarah as injured, not that she died. |

| c | Mike Leigh was born in nearby Salford. |

References

- p. 28

- p. 30

- p. 22

- pp. 194–252

- pp. 1–3

- p. 115

- p. 116

- p. 122

- p. 118

- p. 118

- pp. 22–23

- p. 23

- p. 122

- p. 125

- p. 123

- p. 31

- p. 33

- pp. 22–23

- p. 7

- p. 145

- p. 119

- pp. 152–153

- p. 88

- p. 160

- p. 12

- p. 136

- p. 128

- p. 95

- p. 118

- pp. 120–121

- p. 125

- p. 148

- p. XXV

- p. 33

- p. 19

- pp. 119–120

- p. 161

- pp. 162–163

- p. 129

- p. 167

- pp. 166–167

- p. 8

- p. 168

- p. 156

- p. 170

- pp. 254–276

- p. 185

- p. 180

- p. 214

- p. 175

- p. 181

- pp. 186–187

- pp. 150–151

- p. 187

- p. 12

- p. 1

- p. 31

- pp. 150–151

- p. 65

- p. 74

- p. 77

- p. 79

- p. 86

- p. 90

- p. 92

- p. 105

- p. 115

- p. 139

- p. 254

- p. 201

- pp. 21–30

- p. 6

- pp. 30, 35

- pp. 203–204

- p. 195

- p. 154

- p. 272

- p. 211

- pp. 32–33

- p. 218

- p. 25

- p. 204

- pp. 133–134