Quatermass and the Pit is a British television science-fiction serial transmitted live by BBC Television in December 1958 and January 1959. It was the third and last of the BBC’s Quatermass serials, although the chief character, Professor Bernard Quatermass, reappeared in a 1979 ITV production called Quatermass. Like its predecessors, Quatermass and the Pit was written by Nigel Kneale.

The serial continues the loose chronology of the Quatermass adventures. Workmen excavating a site in Knightsbridge, London, discover a strange skull and what at first appears to be an unexploded bomb. Quatermass and his newly appointed military superior at the British Rocket Group, Colonel Breen, become involved in the investigation when it becomes apparent that the object is an alien spacecraft. The ship and its contents have a powerful and malign influence over many of those who come in contact with it, including Quatermass. It becomes obvious to him that the aliens, probably from Mars, had been abducting pre-humans and modifying them to give them psychic abilities much like their own before returning them to Earth, a genetic legacy responsible for much of the war and racial prejudice/strife in the world.

Background

The Quatermass Experiment (1953) and Quatermass II (1955), both written by Nigel Kneale, had been critical and popular successes for the BBC,[1][2] and in early 1957 the corporation decided to commission a third serial. Kneale had left the BBC shortly before, but was hired to write the new scripts on a freelance basis.[3]

The British Empire had been in transition since the 1920s, and the pace accelerated in the wake of the Second World War. More and more member states demanded independence, and a series of crises erupted during the 1950s, including the 1952 Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya and the Suez Crisis of 1956. During the same period immigration into Britain from the Indian subcontinent and the Caribbean was on the increase, causing some resentment among elements of the British. At the time Kneale was working on his scripts black communities in Nottingham and London came under attack from mobs of white Britons;[4] Kneale became keen to develop the serial as an allegory for the emerging racial tensions that culminated in the Notting Hill race riots of August and September 1958.[5]

Plot

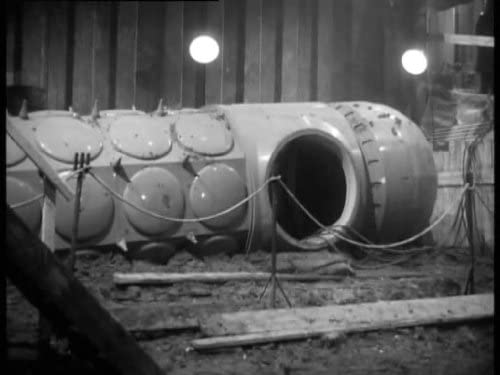

Workmen discover a pre-human skull while building in the fictional Hobbs Lane (formerly Hob’s Lane, Hob being an antiquated name for the Devil) in Knightsbridge, London. Dr Matthew Roney, a paleontologist, examines the remains and reconstructs a dwarf-like humanoid with a large brain volume, which he believes to be a primitive man. As further excavation is undertaken, something that looks like a missile is unearthed; further work by Roney’s group is halted because the military believe it to be an unexploded Second World War bomb.

Roney calls in his friend Professor Bernard Quatermass of the British Rocket Group to prevent the military from disturbing what he believes to be an archaeological find. Quatermass and Colonel Breen, recently appointed to lead the Rocket Group over Quatermass’s objections, become intrigued by the site. As more of the artefact is uncovered additional fossils are found, which Roney dates to five million years, suggesting that the object is at least that old. The interior is empty, and a symbol of six intersecting circles, which Roney identifies as the occult pentacle, is etched on a wall that appears to conceal an inner chamber.

The shell of the object is so hard that even a borazon boron nitride drill makes no impression, and when the attempt is made, vibrations cause severe distress in people around the object. Quatermass interviews local residents and discovers ghosts and poltergeists have been common in the area for decades. An hysterical soldier is carried out of the object, claiming to have seen a dwarf-like apparition walk through the wall of the artifact, a description that matches a 1927 newspaper account of a ghost.

Following the drilling, a hole opens up in the object’s interior wall. Inside, Quatermass and the others find the remains of insect-like aliens resembling giant three-legged locusts, with stubby antennae on their heads giving the impression of horns. As Quatermass and Roney examine the remains, they theorize the aliens may have come from a planet habitable five million years ago – Mars.

While clearing his equipment from the craft, the drill operator triggers more poltergeist activity, and runs through the streets in a panic until he finds sanctuary in a church. Quatermass and Roney find him there, and he describes visions of the insect aliens killing each other. As Quatermass investigates the history of the area, he finds accounts dating back to medieval times about devils and ghosts, all centred on incidents where the ground was disturbed. He suspects a psychic projection of these beings has remained on the alien ship and is being seen by those who come into contact with it.

Quatermass decides to use Roney’s optic-encephalogram, a device that records impressions from the optical centers of the brain, and see the visions for himself. Roney’s assistant, Barbara Judd, is most sensitive; placing the device on her, they record a violent purge of the Martian hive to root out unwanted mutations. Quatermass concludes that in its most primitive phase mankind was visited by this race of Martians. Some apes and primitive pre-humans were taken away and genetically altered to give them abilities such as telepathy, telekinesis and other psychic powers. They were then returned to Earth, and the buried artifact is one of the ships that had crashed at the end of its journey. With their home world dying, the aliens had tried to change humanity’s ancestors to have minds and abilities similar to their own, but with a bodily form adapted to life on Earth.

But the aliens became extinct before completing their work. As the human race bred and evolved, a percentage retained their psychic abilities, which surfaced only sporadically. For centuries the buried ship had occasionally triggered those dormant abilities, which explained the reports of poltergeists; people were unknowingly using their own telekinesis to move objects around, and the ghost sightings were traces of a racial memory. The authorities, and Breen in particular, find this explanation preposterous despite being shown the recording of Barbara’s vision. They believe that the craft is a Nazi propaganda weapon and the alien bodies fakes designed to create exactly the impressions that Quatermass has succumbed to, and decide to hold a media event to stem the rumors that are already spreading.

Quatermass warns that if implanted psychic powers survive in the human race, there could also still be an ingrained compulsion to enact the “Wild Hunt” of a race purge, but the media event goes ahead regardless. The power cables that string into the craft fully activate it for the first time, and glowing and humming like a living thing it starts to draw upon this energy source and awaken the ancient racial programming. Those Londoners in whom the alien admixture remains strong fall under the ship’s influence; they merge into a group mind and begin a telekinetic mass murder of those without the alien genes, an ethnic cleansing of those the alien race mind considers to be impure and weak.

Breen stands transfixed and is eventually consumed by the energies from the craft as it slowly melts away and an image of a Martian “devil” floats in the sky above London. Fires and riots erupt, and Quatermass succumbs to the mass psychosis and attempts to kill Roney, who lacks the alien gene and is immune to alien influence. Roney manages to shake Quatermass out of his trance, and remembering the legends of demons and their aversion to iron and water, proposes that a sufficient mass of iron connected to wet earth may be sufficient to short-circuit the apparition. Quatermass acquires a length of iron chain and tries to reach the “devil” but succumbs to its psychic pressure. Roney manages to walk up to the apparition and hurls the chain at it, resulting in him and the spacecraft being reduced to ashes.

At the conclusion of the final episode Quatermass gives a television broadcast, at the end of which he delivers a warning directly to camera: “If we cannot control the inheritance within us, this will be their [the Martians’] second dead planet.”[6]

Episode list

| No. | Title | Directed by | Written by | Original air date | Prod. code | UK viewers (millions) |

| 1 | “The Halfmen” | Rudolph Cartier | Nigel Kneale | 22 December 1958 | T/5133 | 7.6 |

| 2 | “The Ghosts” | Rudolph Cartier | Nigel Kneale | 29 December 1958 | T/5134 | 9.1 |

| 3 | “Imps and Demons” | Rudolph Cartier | Nigel Kneale | 5 January 1959 | T/5135 | 9.8 |

| 4 | “The Enchanted” | Rudolph Cartier | Nigel Kneale | 12 January 1959 | T/5136 | 9.5 |

| 5 | “The Wild Hunt” | Rudolph Cartier | Nigel Kneale | 19 January 1959 | T/5137 | 10.6 |

| 6 | “Hob” | Rudolph Cartier | Nigel Kneale | 26 January 1959 | T/5138 | 11.9 |

Cast

For the third time in as many serials the title role was played by a different actor, this time by André Morell; the part had initially been offered to Alec Clunes, but he declined it.[7] Morell had a reputation for playing authority figures, such as Colonel Green in The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957),[8] and had previously worked with Kneale and Cartier when he appeared as O’Brien in their BBC television adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four (1954).[9] He had been the first actor offered the part of Quatermass, for the original serial The Quatermass Experiment in 1953, but he turned the part down.[10] Morell’s portrayal of Quatermass has been described as the definitive interpretation of the character.[11]

Colonel Breen was played by Anthony Bushell, who was known for various similar military roles – including another bomb disposal officer in The Small Back Room (1949) – and preferred to be addressed as “Major Bushell”, the rank he held during the Second World War.[12] Roney was played by Canadian actor Cec Linder, John Stratton played Captain Potter, and Christine Finn played the other main character, Barbara Judd.[8] She went on to provide the voices for various characters in the popular 1960s children’s television series Thunderbirds.[13]

For the first time, Kneale used a character from a previous serial other than Quatermass himself, the journalist James Fullalove from The Quatermass Experiment. The production team had hoped that Paul Whitsun-Jones would be able to reprise the part, but he was unavailable, and Brian Worth was cast instead.[3] Michael Ripper appeared as an army sergeant; he had been in Hammer Film Productions’ adaptation of the second Quatermass serial, Quatermass 2, the previous year.[14]

Production

Filming

The director assigned was Rudolph Cartier, with whom Kneale had a good working relationship;[15] the two had collaborated on the previous Quatermass serials, as well as the literary adaptations Wuthering Heights (1953) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1954).[16] The budget of £17,500 (equivalent to about £366,000 as at 2018[17]) allocated for Quatermass and the Pit was larger than that of the previous Quatermass productions.[18] Pre-production began in September 1958, while Cartier was still working on A Tale of Two Cities and A Midsummer Night’s Dream for the BBC. As the two previous Quatermass serials had been scheduled in half-hour slots but, performed live, had overrun, Cartier requested 35-minute slots for the six episodes of Quatermass and the Pit. This was agreed in November 1958, just before the start of production on 24 November. The six episodes – “The Halfmen”, “The Ghosts”, “Imps and Demons”, “The Enchanted”, “The Wild Hunt” and “Hob” – were broadcast on Monday nights at 8 pm from 22 December 1958 to 26 January 1959.[3]

Each episode was predominantly live from Studio 1 of the BBC’s Riverside Studios in Hammersmith, London. The episodes were rehearsed from Tuesday to Saturday, usually at the Mary Wood Settlement in Tavistock Place, London, with camera rehearsals in the morning and afternoon of transmission. Not every scene was live; a significant amount of material was on 35 mm film and inserted during the performance. Most filming involved scenes set on location or those too technically complex or expansive to achieve live.[3] The latter were shot at Ealing Studios, acquired by the BBC in 1955,[19] where Cartier worked with the cinematographer A. A. Englander.[20] Pre-filming was also used to show the passage of time in the second episode; the archaeological dig at Ealing was shown to have dug deeper into the ground than the equivalent set at Riverside, enabling a sense of time having elapsed that would not have been possible in an all-live production.[3]

Made just before videotape became general at the BBC, all six episodes of Quatermass and the Pit were preserved for a possible repeat by being telerecorded on 35 mm film.[3] This was achieved with a specially synchronised film camera capturing the output of a video monitor; the process had been refined throughout the 1950s, and recordings of Quatermass and the Pit are of high technical quality.[21] The serial was repeated in edited form as two 90-minute episodes, entitled “5 Million Years Old” and “Hob”, on 26 December 1959 and 2 January 1960. The third episode, “Imps and Demons”, was re-shown on BBC Two on 7 November 1986 as part of the “TV50” season, celebrating 50 years of BBC television.[3]

Quatermass and the Pit was the last original production on which Kneale collaborated with Rudolph Cartier.[22]

Special effects

Special effects were handled by the BBC Visual Effects Department, formed by Bernard Wilkie and Jack Kine in 1954.[23] Kine or Wilkie oversaw effects on a production; due to the number of effects, both worked on Quatermass and the Pit.[24] The team pre-filmed most of their effects for use during the live broadcasts.[18] They also oversaw practical effects for the Ealing filming and Riverside transmission,[3] and constructed the bodies of the Martian creatures.[25]

Music

The music was credited to Trevor Duncan, a pseudonym used by BBC radio producer Leonard Trebilco, whose music was obtained from stock discs.[3] Quatermass and the Pit also used sound effects and electronic music to create a disturbing atmosphere.[26] These tracks were created for the serial by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, overseen by Desmond Briscoe; Quatermass and the Pit was one of the productions for which Briscoe and the workshop became most renowned.[27][28] It was the first time electronic music had been used in a science-fiction television production.[28]

Reception

Quatermass and the Pit was watched by an average audience of 9.6 million viewers, peaking at 11 million for the final episode.[29] The Times‘ television reviewer praised the opening episode the day after its transmission. Pointing out that “Professor Bernard Quatermass … like all science fiction heroes, has to keep running hard if he is not to be overtaken by the world of fact”, the anonymous reviewer went on to state how much he had enjoyed the episode as “an excellent example of Mr. Kneale’s ability to hold an audience with promises alone; smooth, leisurely, and without any sensational incident”.[30]

Kneale went on to use the Martian “Wild Hunt” as an allegory for the recent Notting Hill race riots,[31][a]Kneale himself said in an interview that “I try to give those stories some relevance to what is round about us today. The last one [Quatermass and the Pit], for instance, was a race-hate fable.”[32] but some Black British leaders were upset by the depiction of racial tensions in the first episode. “Leaders of coloured minorities here to-day criticized the BBC for allowing a report that ‘race riots are continuing in Birmingham,’ to be included in a fictional news bulletin during the first instalment of the new Quatermass television play last night”, reported The Times‘ Birmingham correspondent.[33]

These themes and subtexts were highlighted by the British Film Institute’s review of the serial when it was included in their TV 100 list in 2000, in 75th position – 20th out of the dramas featured: “In a story which mined mythology and folklore … under the guise of genre it tackled serious themes of man’s hostile nature and the military’s perversion of science for its own ends.”[8] The theme of military takeover of peaceful scientific research was also considered favourably by Patrick Stoddart, writing for The Sunday Times in 1988: “Last week I watched a BBC drama in which a scientist fought against smirking government ministers and power-crazed army officers to stop his peaceful rocket research group being turned into a Star Wars vehicle to put missiles on the moon. They won.”[34]

Influence

In a 2006 Guardian article Mark Gatiss wrote “What sci-fi piece of the past 50 years doesn’t owe Kneale a huge debt? … The ‘ancient invasion’ of Quatermass and the Pit cast a huge shadow … its brilliant blending of superstition, witchcraft and ghosts into the story of a five-million-year-old Martian invasion is copper-bottomed genius.”[35] Gatiss was a scriptwriter for Doctor Who, a programme that had been particularly strongly influenced by the Quatermass serials throughout its history.[36][37] Derrick Sherwin, the producer of Doctor Who in 1969, acknowledged Quatermass and the Pit‘s influence on the programme’s move towards more realism and away from “wobbly jellies in outer space”.[38] The 1971 and 1977 Doctor Who serials The Dæmons and Image of the Fendahl share many elements with Quatermass and the Pit: the unearthing of an extraterrestrial spaceship, an alien race that has interfered with human evolution and is the basis for legends of devils, demons and witchcraft, and an alien influence over human evolution.[39]

The writer and critic Kim Newman, speaking about Kneale’s career in a 2003 television Timewatch documentary, cited Quatermass and the Pit as perfecting “the notion of the science-fictional detective story”. Newman also discussed the programme as an influence on the horror fiction writer Stephen King, claiming that King had “more or less rewritten Quatermass and the Pit in The Tommyknockers“.[40]

After Quatermass and the Pit Kneale felt that it was time to rest the character: “I didn’t want to go on repeating because Professor Quatermass had already saved the world from ultimate destruction three times, and that seemed to me to be quite enough.”[41] But by the early 1970s he had decided there were new avenues to explore, and the BBC planned a fourth Quatermass serial in 1972.[42] The BBC did not proceed with the project however, and Kneale’s scripts were instead produced in 1979 as a four-part serial for Thames Television titled Quatermass.[43]

Other media

As with the previous two Quatermass serials, the rights to adapt Quatermass and the Pit for the cinema were purchased by Hammer Film Productions. Their adaptation was released with the same title as the original in 1967, directed by Roy Ward Baker and scripted by Kneale.[44] Scottish actor Andrew Keir starred as Quatermass, the role for which he was best remembered and regarded particularly highly in comparison to the previous film’s Quatermass, Brian Donlevy.[45][b]“Keir also made many films … most gratifyingly, perhaps, the movie version of Quatermass and the Pit (1967), when he finally replaced the absurdly miscast Brian Donlevy.”[46] The film, made in colour, is regarded by many commentators as a classic of the genre for the way it blends science fiction with the supernatural.[47][48] In the United States the film was retitled Five Million Years to Earth.[49]

A script book of Quatermass and the Pit was released by Penguin Books in April 1960, with a cover by Kneale’s artist brother Bryan Kneale. In 1979 this was re-published by Arrow Books to coincide with the transmission of the fourth and final Quatermass serial on ITV; this edition featured a new introduction by Kneale. A “living theatre” adaptation of Quatermass and the Pit was staged in a quarry near Nottingham in 1997.[11][50]

For the box set release, Quatermass and the Pit was extensively restored.[51] A process called VidFIRE was applied to all of the scenes originally broadcast live, restoring the fluid interlaced video look they would have had on transmission, but which was lost during the telerecording process. For the pre-filmed scenes, most of the high-quality original 35 mm film inserts still existed, as they had been spliced into the 1959–1960 compilation repeat version in place of the lower-quality telerecorded versions of the same sequences. As this compilation also survived in the BBC archives, these film sequences were able to be digitally remastered and inserted into the newly restored episodic version for the DVD release. The compilation used a separate magnetic soundtrack, and although the original had decayed a safety copy had survived. This yielded better sound quality than the optical soundtracks accompanying the original episodes, and was therefore the main source for the audio remastering except in the case of scenes that were not in the compilation, and in a few cases where faults on the magnetic tracks necessitated their replacement by the optical versions.[21]

Parodies

A 1959 episode of the BBC radio comedy series The Goon Show parodied Quatermass and the Pit in an episode titled “The Scarlet Capsule”. It was written by Spike Milligan, and used the original BBC Radiophonic Workshop sound effects made for the television serial.[3]

The serial was also parodied by the BBC television comedy series Hancock’s Half Hour in an episode titled “The Horror Serial”, transmitted the week after the broadcast of the final episode. In it, Tony Hancock has just finished watching the final episode of Quatermass and the Pit, and becomes convinced that there is a crashed Martian space ship buried at the bottom of his garden. It is in fact an unexploded bomb, although Hancock claims that the warning “Achtung!” is really the Martian for Acton. This episode no longer exists in the BBC’s archives, but a private collector’s audio-only recording has been discovered, and released publicly on the Hancock’s Half Hour Collectibles Volume One CD box set.[3]

It was parodied a third time in a sketch from the final series of The Two Ronnies in 1986, which featured a guest appearance by Joanna Lumley.[3]

Notes

| a | Kneale himself said in an interview that “I try to give those stories some relevance to what is round about us today. The last one [Quatermass and the Pit], for instance, was a race-hate fable.”[32] |

|---|---|

| b | “Keir also made many films … most gratifyingly, perhaps, the movie version of Quatermass and the Pit (1967), when he finally replaced the absurdly miscast Brian Donlevy.”[46] |