Wikimedia Commons

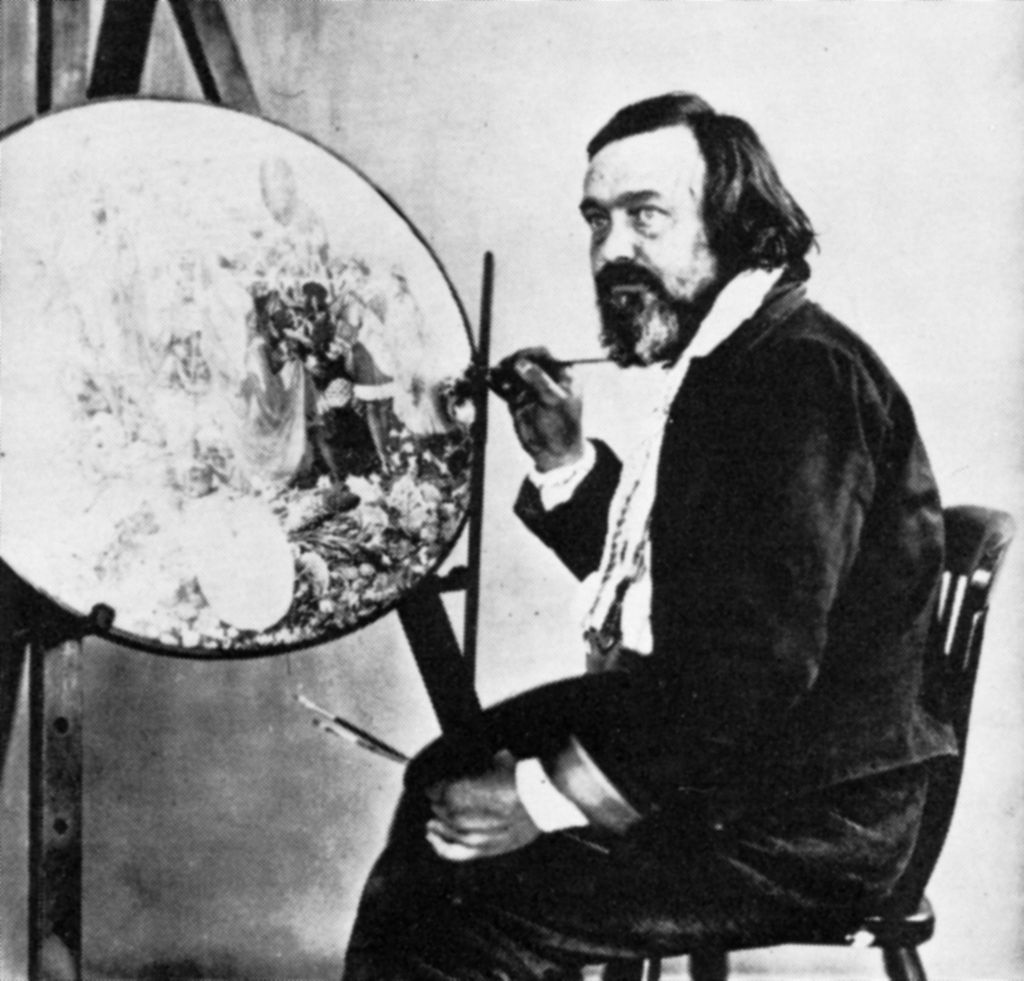

Richard Dadd (1 August 1817 – 7 January 1886) was an English painter of the Victorian era, noted for his depictions of fairies and other supernatural subjects, rendered in obsessively minute detail.

Most of the works for which Dadd is best known were created between 1843 and 1866 while a patient in Bethlem and Broadmoor psychiatric hospitals, where he was incarcerated for the murder of his father, believing him to be the Devil in disguise. His condition today would probably be diagnosed as schizophrenia, then unknown.[1]

Early life

Richard Dadd was born at Chatham, Kent on 1 August 1817, the son of chemist Robert Dadd (1788/9–1843) and Mary Ann (1790–1824), daughter of the shipwright Richard Martin. He was educated at King’s School, Rochester, and was admitted to the Royal Academy Art Schools at the age of 20.[2] Dadd became a leading member of an anti-academic art movement called The Clique, along with several other of the future most celebrated painters of the Victorian era including William Powell Frith and Augustus Egg, a forerunner of the Pre-Raphaelite BrotherhoodGroup of English artists formed in 1848 to counter what they saw as the corrupting influence of the late-Renaissance painter Raphael..[3]

Career

In July 1842 Sir Thomas Phillips, the former mayor of Newport, chose Dadd to accompany him as his draughtsman on an expedition through Europe to Greece, Turkey, Southern Syria and finally Egypt. In November of that year they spent a gruelling two weeks in Southern Syria, passing from Jerusalem to Jordan and returning across the Engaddi wilderness. Toward the end of December, while travelling up the Nile by boat, Dadd underwent a dramatic personality change, becoming delusional, increasingly violent, and believing himself to be under the influence of the Egyptian god Osiris; his condition was initially thought to be caused by sunstroke.[4]

Mental illness, hospitalisation

Following his return to England in May 1843, Dadd immediately resumed his work, and for much of the time behaved normally. But after a period of apparent recovery Dadd’s mental condition again deteriorated. On 28 August 1843 he persuaded his father to accompany him to Cobham Park in Kent, near to his childhood home of Chatham. Believing him to be the Devil in disguise, Dadd stabbed his father to death with a knife and fled to France.[2]

En route to Paris, Dadd attempted to kill a fellow passenger in the carriage in which he was travelling using a razor, and was arrested by police. He confessed to killing his father, and was confined in a French asylum for ten months before being extradited to England in July 1844. After being certified as insane, Dadd was admitted to the criminal lunatic asylum attached to Bethlem Hospital, known as Bedlam, where he remained until 1864, when all the criminal patients were transferred from Bethlem to the new asylum of Broadmoor in Berkshire.[2]

Dadd was encouraged to continue painting while in hospital, and in 1852 he created a portrait of one of his doctors, Alexander Morison, which now hangs in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Many of his masterpieces were produced during this period, including The Fairy Feller’s Master-StrokePainting by the English artist Richard Dadd (1817–1886), considered to be his masterpiece., which he worked on between 1855 and 1864. Also dating from the 1850s are the thirty-three watercolour drawings titled Sketches to Illustrate the Passions, which include Grief or Sorrow, Love, and Jealousy, and Agony-Raving Madness and Murder.[5] Like most of his works, these are executed on a small scale, and feature protagonists whose eyes are fixed in a peculiar, unfocused stare.[6] Dadd also produced many shipping scenes and landscapes during his hospitalisation, including the ethereal 1861 watercolour Port Stragglin. These are executed with a miniaturist’s eye for detail, which belies the fact that they are products of imagination and memory.[7]

Death

Dadd died at Broadmoor on 7 January 1886, “from an extensive disease of the lungs”;[8][a]Tuberculosis.[2] a “substantial number” of his works are on display in the Bethlem Royal Hospital Museum.[2]

Gallery

This article may contain text from Wikipedia, released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.