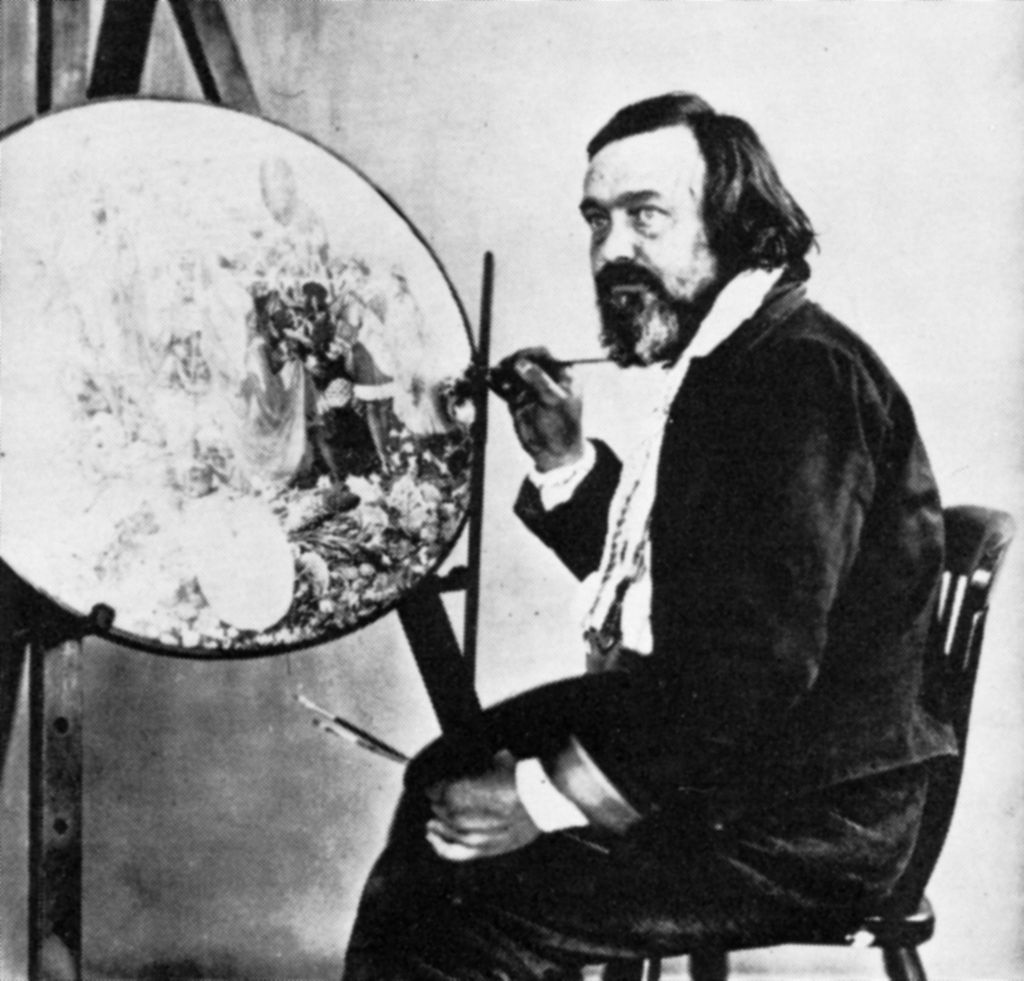

Robert Huskisson (1819–1861) was an English portrait painter who became particularly recognised for his fairy paintingsGenre of art and illustration featuring small imaginary human-like creatures with magical powers, often with wings.. Born in the Langar area of Nottingham in 1819, he was christened Robert Locking Huskinson. Together with his younger sibling, Leonard, they changed the spelling of their surname after the pair moved to London in 1839.[1] Their father, Henry Huskinson, was a portrait painter who seems to have provided their tutoring in art.[2]

Huskisson’s artworks began appearing at the Royal Academy in 1838, although his fairy paintings were not exhibited until 1847. He finally exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1854, after which, possibly due to ill health, he became so obscure that following his death in London on 6 October 1861 no obituary was included in The Art Journal. His work returned to particular prominence after four of his pieces were featured in a Royal Academy exhibition in 1997.[2][3]

In his autobiography, the English painter William Powell Frith scathingly refers to Huskisson as “a very common man, entirely uneducated. The very tone of his voice was dreadful”.[4][a]Maas includes a slightly fuller quotation from Frith’s autobiography; Maas’ version reads: “a very common man, entirely uneducated. I doubt he could read or write. The very tone of his voice was dreadful”.[5] Frith did however go on to acknowledge the “considerable merit” of the artist’s work. His opinion may have been founded on Huskisson’s heavily accented Midlands dialect, as two elegant and well-written letters penned by the artist are held at the Getty Museum in Malibu that render the opinion baseless.[5]

Fairy paintings

Huskisson was among the first artists of his era to specialise in the fairy paintings genre;[6] writing in The Art Union after viewing Huskisson’s 1847 exhibit of The Midsummer Night’s Fairies a contemporary critic predicted a bright future for the artist.[7] The modern-day art historian Christopher Wood described him as “an artist of great lyrical and technical ability, and one of the best Victorian fairy painters”.[6] Likewise, Jeremy Maas, an art historian who specialised in Victorian fairy paintings,[8] considered that Huskisson together with his contemporary John SimmonsEnglish painter and illustrator, recognised as a specialist in painting female fairies, frequently nude. “stood out from the others”.[9] In common with many other artists, such as Daniel Maclise and Edwin Landseer, Huskisson used Shakespearian scenes as the inspiration for his work.[10]

The two works from 1847, The Midsummer Night’s Fairies and Come unto these yellow sands, borrow a theatrical device – a proscenium archPart of a theatre stage in front of the curtain. – to form a decorated frame through which the scene is viewed.[9] Samuel Carter Hall, editor of The Art Union,[b]later The Art Journal[9] was Huskisson’s main patron and he acquired both paintings; engraved versions of each work were later included in The Art Journal.[11] Another of Huskisson’s pictures, The Mother’s Blessing, was reproduced as an engraving for the frontispiece to Anna Maria Hall’s serialised tale Midsummer Eve: A Fairy Tale of Love that appeared in The Art Union.[9][12]

His works demonstrate the influence of William Etty and one of Huskisson’s later pieces – completed by 1853 – reproduces Etty’s Rape of Proserpine.[9][13] Etty’s style can be discerned in the classical figures featured on the proscenium arch of Huskisson’s paintings as well.[14] The influence of Richard Dadd

English painter of the Victorian era , noted for his depiction of fairies and other supernatural subjects. Most were completed while he was an inmate of Bedlam and Broadmoor lunatic asylums. is also evident but Huskisson’s interpretations, particularly in Come unto these yellow sands that was painted as Dadd’s 1842 Academy exhibit, Huskisson’s version is “delicately rendered” and the nymphs are not the “tormented souls” depicted by Dadd.[9][c]Dadd was later committed to an insane asylum; his version of Come unto these yellow sands was the last painting he completed and exhibited before being confined.[9] Reflections of the style of William Edward Frost can be detected yet Huskisson retained a “highly polished style all his own.”[15]

Historians believe only a handful of Huskisson’s pieces remain extant in the 21st-century;[9][11] Wood expresses the wish that: “One can only hope that more of Huskisson’s work will, in time, come to light.”[4]

Notes

| a | Maas includes a slightly fuller quotation from Frith’s autobiography; Maas’ version reads: “a very common man, entirely uneducated. I doubt he could read or write. The very tone of his voice was dreadful”.[5] |

|---|---|

| b | later The Art Journal[9] |

| c | Dadd was later committed to an insane asylum; his version of Come unto these yellow sands was the last painting he completed and exhibited before being confined.[9] |