Rumpelstiltskin is a fairy tale popularly associated with Germany, where it is known as Rumpelstilzchen.[a]Despite efforts to decode the derivation of Rumpelstiltskin’s name, it is essentially meaningless.[1] The tale is one of those collected by the Brothers Grimm in the 1812 edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales).

The Brothers Grimm believed that the folktales they collected dated back thousands of years, predating the birth of the modern Indo-European languages, although later researchers tended to suggest the unlikelihood of such folktales having survived through oral tradition alone. There is some evidence, however, that the Brothers Grimm may have been correct, and that the story of Rumpelstiltskin may in some form be between 2500 and 6000 years old.

Rumpelstiltskin has an Aarne–Thompson–Uther (ATU) type of 500: The Name of the Supernatural Helper, a type of folktale common among the the main European language families.[2]

Wikimedia Commons

Plot

There are many variants of the story, but in the most common a boastful miller, in an effort to impress the king, claims that his daughter can spin straw into gold. The king calls for the girl, shuts her in a tower room filled with straw and a spinning wheel, and demands she spin the straw into gold by morning or he will cut off her head.

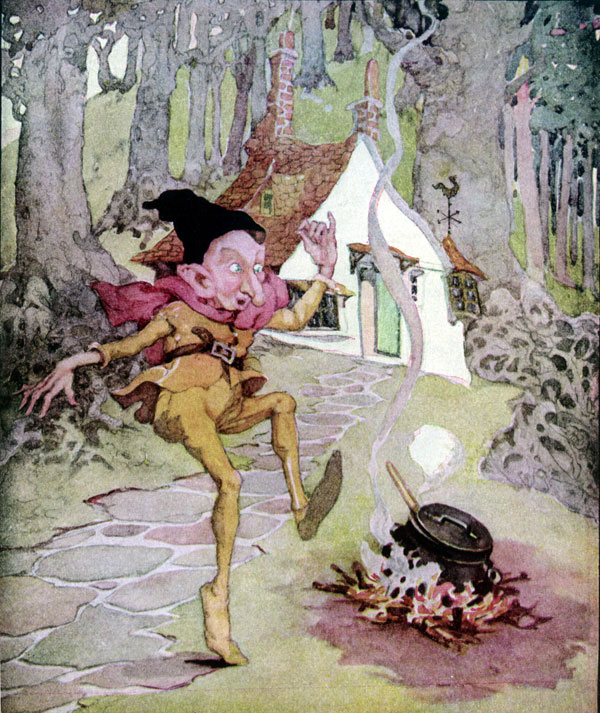

When she has given up all hope, an imp-like creature appears and spins the straw into gold in return for her necklace. When next morning the king takes the girl to a larger room filled with straw to repeat the task, the imp once again spins, in return this time for the girl’s ring.

On the third day the girl is taken to an even larger room filled with straw, and told by the king that he will marry her if she can fill this room with gold or execute her if she cannot. But the girl has nothing left with which she can pay the imp, so he extracts from her a promise that she will give him her firstborn child, before spinning the straw into gold for a final time. In some versions the little man appears and begins to turn the straw into gold, paying no heed to the girl’s protests that she has nothing to pay him with; when he finishes the task, he states that the price is her first child, and the horrified girl objects because she never agreed to this arrangement.

The king keeps his promise to marry the miller’s daughter, and when their first child is born, the imp returns to claim his payment. The girl offers him all the wealth she has not to take the child, but the imp has no interest in her riches. He does though finally agree to give up his claim if she can guess his name within three days (some versions have the imp limiting the number of daily guesses to three and hence the total number of guesses allowed to a maximum of nine).

The girl’s many guesses are incorrect, but before the final night, she wanders into the woods in search of the imp; in some versions she sends a servant into the woods instead of going herself, to allay the king’s suspicions. She comes across his remote mountain cottage, and watches unseen as the imp hops about his fire singing “tonight tonight, my plans I make, tomorrow tomorrow, the baby I take. The queen will never win the game, for Rumpelstiltskin is my name”.

When the imp comes to the queen on the third day, after initially feigning ignorance, she reveals his name to be Rumpelstiltskin, and he loses his temper, blaming the Devil for having given his name to the queen. In the 1812 edition of the Brothers Grimm tales, Rumpelstiltskin then “ran away angrily, and never came back”.

The ending was revised in later editions to a more gruesome conclusion, in which Rumpelstiltskin drives his foot so hard that his leg goes into the earth. In a passion to release himself, he seizes his other foot with both hands and tears himself in two. Other versions also have Rumpelstiltskin driving his foot into the ground, but after some effort to free himself he stomps off to the mocking jeers of the court.[3]

Origins

The Brothers Grimm believed that many of the stories they helped to popularise were rooted in a shared cultural history dating back to the birth of the Indo-European language family some 2500–6000 years ago, although the stories were not written down until the 16th and 17th centuries. Later scholarship tended to suggest that the tales were unlikely to have survived for thousands of years in oral form alone, but recent research has provided evidence to suggest that the Brothers Grimm may have been correct, and that these folktales were originally “probably told in an extinct Indo-European language”.[4][5]

Variations

The tale appears in slightly different forms in almost all European countries, and the 1812 version published by the Brothers Grimm was itself an amalgam of four different versions found in the German state of Hesse. In British variations, the imp goes by names which include Terrytop, Whuppity Stoorie, and Tom Tit Tot.[1][3]

The original 1812 version of Rumperstiltskin makes no mention of a spinning wheel, and no explanation of how the little man was able to transform straw into gold; the spinning wheel was introduced in the 1857 version of the story.[1]

Other uses

The queen’s gain of control over Rumpelstiltskin by knowing his name has its correspondence in the psychological condition in which sufferers attempt to give an impression of understanding something by naming it, known as the Rumpelstiltskin phenomenon.[6]