Sarah Baker (1736/7 – 20 February 1816), née Wakelin, was an English actor and theatre manager of the late Georgian era,[1] who despite being unable to write more than her own name,[2] became one of the most successful self-made women of her time.[3] Sarah was born in London, the daughter of Ann Wakelin (d. 1787), an acrobatic dancer and troupe manager at Sadler’s Wells, and James Wakelin (fl. 1749–1779), a minor actor.[1] She grew up travelling the country with her younger sister Mary in their mother’s small touring company, entertaining the crowds at country fairs and the like.[3] Sarah, along with her sister, performed as a dancer and a puppeteer.[1]

Marriage and early business career

On 6 January 1760 Sarah married a Mr Baker, an acrobat in her mother’s company who may have been the clown-tumbler known as Polander. The couple had three children: Ann, Henry, and Sarah.[1] Following her husband’s death in about 1769 Sarah took over the management of her mother’s company, which toured the Canterbury Circuit for thirty years.[4] The actors included many family members, including Sarah’s children, her sister Mary, and until her retirement in 1777 her mother. She also employed many popular entertainers of the day, offering all her performers a regular salary instead of the more usual share of the profits. Following her mother’s retirement in 1778, Sarah’s company began to stage plays as well as their customary fairground variety acts. Their repertoire included several works by Shakespeare, including Hamlet, Macbeth, Richard III, As You Like It, and The Merchant of Venice, along with comical pieces such as Thomas Dibdin’s The Merry Hop-Pickers.[1]

Theatre management

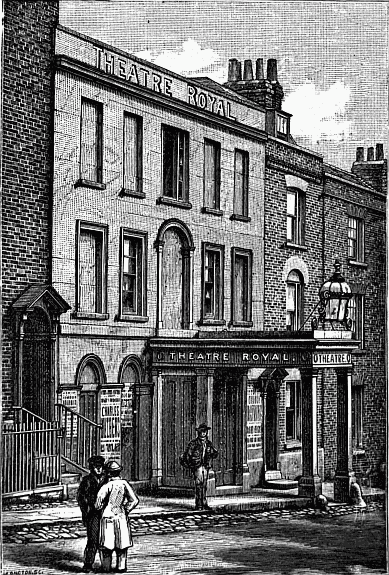

Sarah’s company toured all over Kent, performing in temporary, makeshift facilities until in 1789 she opened the first of her purpose-built theatres in the county. She eventually established a circuit of ten theatres across Kent,[5] with four “great grand” theatres, one each in Canterbury, Rochester, Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells.[3] All were built to the same plan and similar dimensions, to allow for scenery to be easily moved between them. All entrances led to a single box office, where Sarah herself took the money for the seats. Next to some theatres she also built houses to accommodate the performers, which she let out of season.[1]

Sarah’s biographer J. Milling has described her management style as “combative”, and financially “hard-headed”, but she treated members of her company well, paying them regularly and providing them with reasonably priced accommodation. The English dramatist and songwriter Thomas Dibdin (1771–1841), who worked with Sarah, described her as having:

He did add, however, that Sarah could “sometimes descend to lingual expression more idiomatic of Peckham-fair technicals than the elegance to be expected from a directress of the British drama”.[7]

Later life and death

Sarah’s son-in-law William Downton took over management of the company in June 1815. She died in her home in Rochester, beside the Theatre Royal she had built,[8] on 20 February 1816, and was buried in the churchyard at Rochester Cathedral. Her estate was valued at £16,000, equivalent to about £1.2 million as at 2019.[1][a]Using the retail price index.[9]

Notes

| a | Using the retail price index.[9] |

|---|