Wikimedia Commons

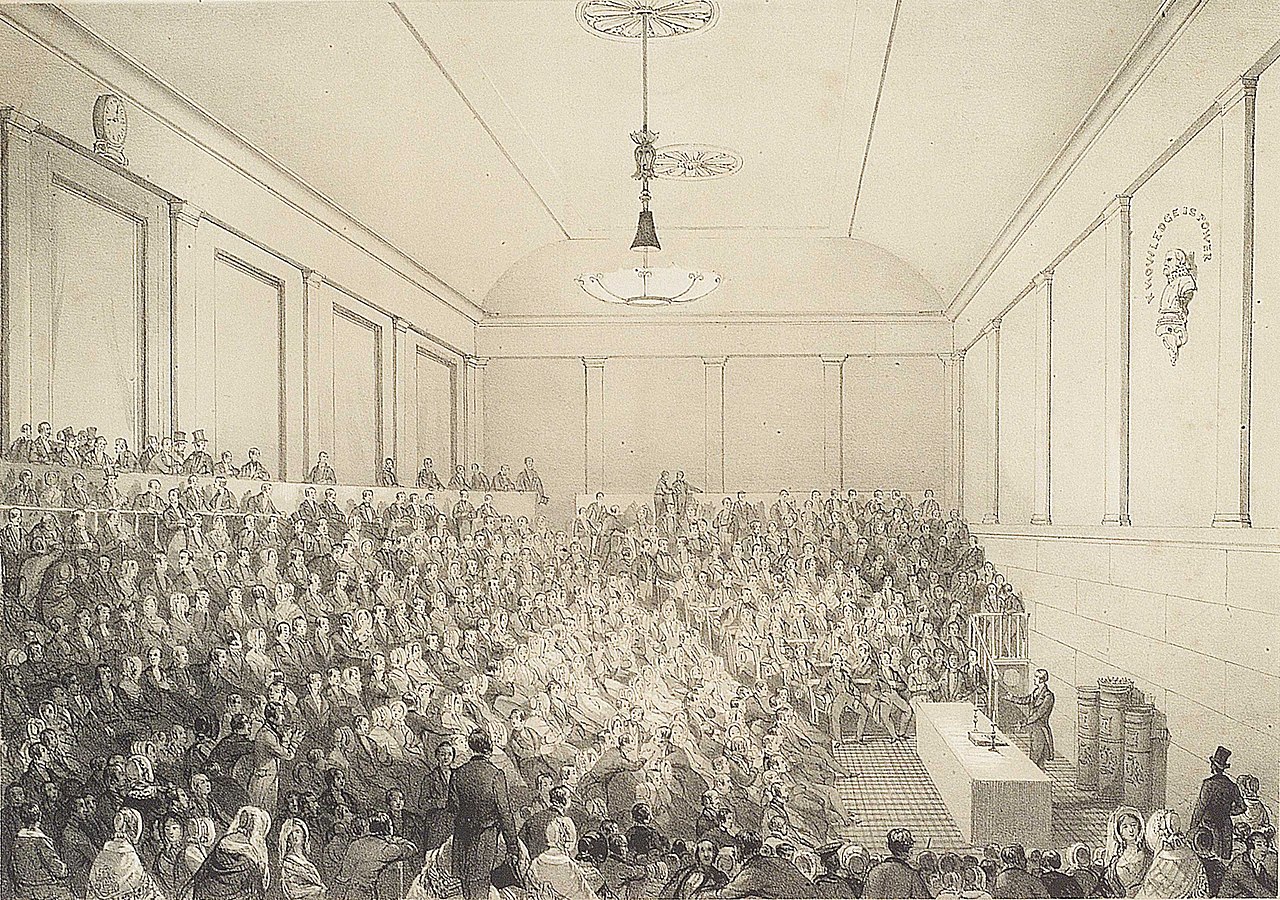

The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (SDUK) was founded in London in 1826, thanks largely to the efforts of the Whig Member of Parliament (MP) Henry Brougham, with the object of publishing cheap and accessible works on science and the arts.

Brougham considered that mass education was an essential prerequisite for political reform, and in October 1824 had contributed an article on “scientific education of the people” to the Whig Edinburgh Review, arguing that popular education would be greatly enhanced by the encouragement of cheap publications to complement the numerous recently founded provincial mechanics’ institutes, a version of which was issued as a pamphlet the following year, titled Practical Observations upon the Education of the People Addressed to the Working Classes and Their Employers.[1]

Brougham wrote the society’s first treatise, Discourse on the Objects, Advantages and Pleasures of Science, which sold 39,000 copies, and he continued to contribute regularly to the society’s various publications until its demise in 1846.[2]

The society’s first committee included many Fellows of the Royal Society and MPs, as well as twelve founding committee members of the newly formed University College London.[3]

Activities

The SDUK’s publishing programme began with the Library of Useful Knowledge. Sold for sixpence,[a]2½p in decimal currency. and published fortnightly, its books focused on scientific topics. Like many other works in the new genre of popular science – such as the Bridgewater Treatises and Humphry Davy’s Consolations in Travel – the books of the Library of Useful Knowledge dealt with fields of scientific progress such as uniformitarianism in geology, the nebular hypothesis in astronomy and the scala naturae in the life sciences. According to the historian James A. Secord, such works met a demand for “general concepts and simple laws”, and in the process helped establish the authority of professional science and scientific specialisms.[4]

The first volume of the Library of Useful Knowledge, an introduction to the series by Brougham on the “objects, advantages and pleasures of science”, sold more than 33,000 copies by the end of 1829. But despite its initial success it soon became clear that the content was too demanding for many readers, leading the society to offer more varied and attractive publications, starting with the Library of Entertaining Knowledge (1829–1838) and The Penny MagazineIllustrated British magazine aimed at a working-class readership, published from 1832 until 1845. (1832–1845), a lavishly illustrated weekly that achieved unprecedented success, with sales in excess of 200,000 copies in its first year.[5][6]

Publications

- Library of Useful Knowledge (1827–1846)

- British Almanac (1828–1914; and associated Companion)

- Library of Entertaining Knowledge (1829–1838)

- Working Man’s Companion (1831–1832)

- Quarterly Journal of Education (1831–1835)

- Penny Magazine (1832–1845)

- Gallery of Portraits (1832–1834)

- Penny Cyclopaedia (1833–1843)

- Library for the Young (1834–1840)

- Farmers Series (1834–1837), which included works by the veterinary surgeon William Youatt on animals kept on farms.[7]

- Biographical Dictionary (1842–1844)

This article may contain text from Wikipedia, released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.