Southport Pier in Southport, Merseyside, England opened in August 1860, is the oldest iron pier in the country. At 1108 metres (3,635 ft) in length, it is also the second-longest in Great Britain, after Southend Pier. Although at one time spanning 1340 metres (4,396 ft), a succession of storms and fires during the late 19th and early 20th centuries reduced its length to that of the present day.

The pier has been host to famous entertainers, including Charlie Chaplin in the early 20th century. It was visited by steamliners in its heyday, but silting of the channel meant that by the 1920s very few were able to reach the pier, and the service ceased in 1929. The pier fell into disrepair throughout the late 20th century, and by 1990 it was operating at a significant annual loss with rising maintenance costs. The local council sought to have the pier demolished, but were defeated in their attempt by a single vote.

The pier was significantly restored during 2000–2002, and opened to the public in May 2002. The Southport Pier Tramway ran from Southport Promenade to the pier head at various times in the pier’s history with various rolling stock, most recently until June 2015.[1]

The pier is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade II listed building, first listed on 18 August 1975.

Location

At 1108 metres (3,635 ft)[2] Southport Pier is the second longest in Great Britain.[3] As a result of silting in the water channel, part of the pier now passes overland before reaching the beach, as the silt has allowed land beneath the pier to be reclaimed.[4] The entrance starts at Promenade Road and follows a route inland next to Princes Park, before crossing over Marine Drive and meeting the beach at approximately half-way along its length.

The area that now houses the marine lake and surrounding road at the land-end of the pier was acquired by the pier corporation in 1885, following population growth in the local area and pier extensions in the 1870s.[5] In the late 1920s the council reclaimed a large area of the beach to build an urban park, consisting of a lake, miniature railway and car parking.[6]

History

19th century

Proposals for a pier in Southport were first suggested in 1844, in conjunction with a potential railway from Manchester,[7] and a committee was formed in 1852 to help promote its construction.[8] Following debates throughout the following few years about what its intended usage should be, the Southport Pier company was formed in March 1859 with a capitalisation of £12,000. The cost of building the pier was estimated at £8,000 (equivalent to £850,000 in 2018[a]Using the GDP deflator at Measuring Worth.[9]), eventually rising to £8,700; construction work began in August 1859. The pier’s primary purpose was to be a promenade as opposed to a ship-docking pier, and it is therefore considered to be the country’s first pleasure pier.[8]

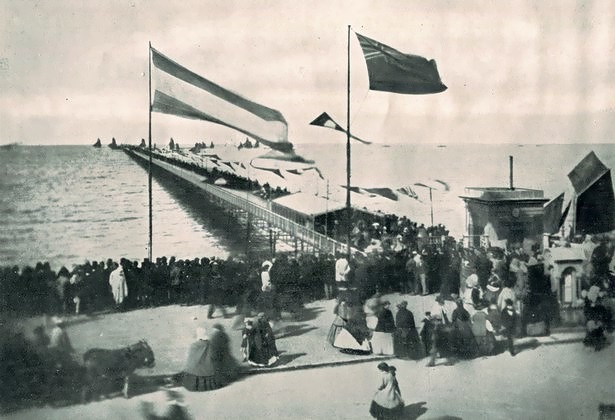

The pier was officially opened with a grand procession on 2 August 1860; at 1100 metres (3,609 ft) it was the second-longest and first iron-constructed pleasure pier in the country.[4] Waiting rooms for boat passengers were added during the pier’s first few years of operation, and a cable-operated tramway had been installed by 1865. The pier was extended to 1340 metres (4,396 ft) in 1868[2] and was used by various steamer ships, including those of the Blackpool, Lytham and Southport Steam Packet Company, with services operating from the pier to resorts including Fleetwood and Llandudno.[10]

Visitors to the pier had to pay a toll, priced deliberately high at 6d (equivalent to £17.50 in 2018[b]Comparing average earnings in 1860 to 2018.[9]) to ensure only the most affluent could afford it. As the 1870s progressed, the numbers of working class visitors increased and tolls were reduced to 2d.[5]

Storm damage was a frequent occurrence – several storms caused damage to the pier’s foundations and buildings throughout the late 1880s and early 1890s. A fire in September 1897 destroyed the original pavilion; its replacement was opened in January 1902 and considered grander, with the inclusion of an auditorium.[5]

20th century

A popular attraction from 1903 were an array of divers, typically diving from the tea house roof several times daily; the most popular and longest-serving were Professors Osbourne and Powsey, the latter frequently jumping off the pier on a bicycle.[11] From 1906 the newly constructed pavilion was leased out to play host to a variety of entertainers, including Charlie Chaplin and George Robey. Following the First World War, the pavilion was renamed the Casino and its main attraction on offer was dancing. This period was a financial success for the pier, with a net profit of £9,155 in 1913 (equivalent to £885,000 in 2018[c]Using the retail price index at Measuring Worth.[9]), and an annual average profit of £6,750 during the 1920s.[12]

By the early 1920s silting in the water channel allowed for land reclamation, whilst it became more and more difficult for steamer ships to reach the pier; the service ceased entirely in 1929.[12] Profits fell during the 1930s depression, compounded with a large fire in July 1933 destroying the pier head. The cost of damage was estimated at £6,000, which was beyond the means of the Southport Pier Company, who ended up selling the pier to Southport Corporation in June 1936 for £34,744 (equivalent to £2.13 million in 2018[d]Using the GDP deflator at Measuring Worth.[9]).[6]

The pier was closed to the public during the Second World War to house and operate searchlights to detect enemy aircraft travelling to Liverpool docks, yet was not physically separated from the land like other piers were during this time.[3] The pier did not reopen again until 1950[13] and in June 1959, suffered a significant fire which destroyed 460 square metres (4,951 ft2) of decking, reducing its length to the present day 3633 feet (1,107 m)[2] and for a period of time making it the third-longest pier after Herne Bay Pier, until that was destroyed by a storm in 1978.[6] Sefton Council acquired ownership of the pier in 1974 following national reorganisation of local government[14] and it was designated as a Grade II listed structure on 18 August 1975,[15] despite being in a state of deterioration. A grant of £62,400 (equivalent to £206,816 in 2018) was awarded in 1983 by the European Regional Development Fund to strengthen the pier’s structure.[16]

Deterioration continued during the latter 20th century, and was hastened by a storm in 1989 which caused extensive damage. Despite the pier’s listed status, Sefton Council sought to demolish the pier in December 1990 due to the rising cost of repairs and maintenance, yet was defeated by a single vote. [4] Operating at an annual loss of £100,000[14] and with estimates close to £1 million to secure the future of the pier, plus a further £250,000 required every five years for repainting, a charitable trust was formed in 1993 to upkeep the pier; various funding was secured in the subsequent years to maintain the pier’s operation.[2] In November 1996 the pier received a heritage grant of £64,000 from the National Heritage Memorial Fund to support its restoration,[17] followed a further grant of £34,000 from the same source the following February to pay for a structural survey to be undertaken;[18] the report confirmed the pier’s then poor condition and recommended its closure.[19]

21st century

Restoration work began in 2000 and was completed in 2002 at a cost of £7.2 million; the pier reopened to the public in May 2002, complete with a new tram.[20] The project formed part of a wider redevelopment strategy, which included a new sea wall to help prevent flooding, landscaping around the pier and a new £28 million Ocean Plaza shopping complex.[21]

The pier today is an open structure, with modern railings on an older base and a deck made of hardwood slats, affording a partial view of the sea below.[22] Along the walkway are name plaques that local people funded to help towards raising the restoration funds.[23] The modern pavilion structure at the pier head was designed by Liverpool architects Shed KM and cost £1.2 million; the building houses a cafeteria with airport style floor to ceiling windows overlooking the beach[22] and a collection of vintage mechanical amusement machines and penny arcade. The exhibition of Edwardian and Victorian machines operates on pre-decimalisation pennies,[20] available to purchase on-site at £1 for 10 old pennies.[23]

Plans were announced in April 2017 to renovate the pier as part of a £2.9 million makeover, with two-thirds of the cost coming from the Coastal Communities Fund to include repairs and new retail units. Additionally, the council seek to undertake repainting and mechanical works, as well as pavilion improvements and providing easier access to the pier from the beach.[24]

Tramway

Initially the pier had a baggage line from 1863, although this was replaced in 1864 when the pier was widened[2] to provide a steam-driven tramway capable of transporting passengers and their luggage.[4]The line was re-laid in 1893, with electrification coming in April 1905. The rolling stock was rebuilt in 1936 when the line was taken over by Southport Corporation.[2] The pier was closed during the Second World War, but when it reopened the tram did not reopen with it, as the town had lost its supply of DC electricity.[4] The tram line eventually reopened in 1950, with the track gauge changed and moved to the side of the pier (previously central) and from 1954 operated with new diesel trains, known as the Silver Belle[13] and built by local engineer Harry Barlow, who owned the Lakeside Miniature Railway.[2] The stock was replaced in 1973 with English Rose, which operated until the mid-1990s, at which time there were doubts over the pier’s future.[13] The Silver Belle stock became derelict at Steamport for some years, before moving to the West Lancashire Light Railway for conversion into carriages.[25]

The restoration in 2002 provided a new 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) narrow gauge tram track in the centre of a widened deck[25] and on 1 August 2005,[26] a new twin-section articulated, battery-powered tram[27] car started service on this track, with a passenger capacity of 74 people.[25]

In July 2013, the tram service was suspended following the discovery of cracks within the supporting columns[28] and ceased running entirely in June 2015 owing to rising maintenance costs and council cost-cutting measures. It was replaced by an extension of a pre-existing smaller land train,[1] and the tram was removed for sale in March 2016.[29]