Spiritualism is a system of beliefs and practices intended to establish communication with the spirits of the dead.[1] It encompasses two major tenets: that the survival of the human personality beyond the death of the body can be proven, and that by various practices it is possible to communicate with the spirits of the dead.[2] Such practices have included table-turning, automatic writing and historically necromancy Form of magic in which the dead are re-animated and able to communicate with the sorcerer who invoked them, just as they would if they were alive., but principally today the services of mediums, who claim to be able to make contact with the souls of the dead.[1]

Form of magic in which the dead are re-animated and able to communicate with the sorcerer who invoked them, just as they would if they were alive., but principally today the services of mediums, who claim to be able to make contact with the souls of the dead.[1]

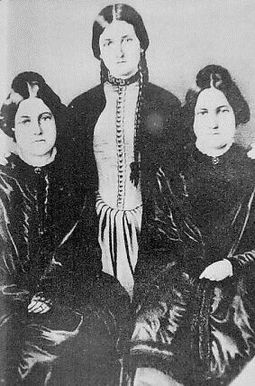

In its modern form Spiritualism dates from the experiences of the American Fox family in 1848.[1] The three Fox sisters – Kate, Maggie and Leah – became famous for their public séances, and established many of the familiar features of subsequent Spiritualism, such as the medium’s trance, and the questioning of spirits through a medium.[3]

Although inherently a religion, early adherents generally avoided organising as a church until The National Spiritualist Association, now the National Spiritualist Association of Churches, was formed in 1893 – the year of Maggie Fox’s death – at a convention in Chicago, Illinois.[4][5]

Origin of the modern form

On 31 March 1848 twelve-year-old Kate and her thirteen-year-old sister Maggie were said by the family to have made contact with a spirit,[6] later claimed to be that of a murdered peddler whose body had been buried in the cellar of the family home.[a]Despite excavations, no body was ever found.[7] The alleged spirit was able to respond to questions through rapping noises, and identified its murderer as John Bell, a former resident of the house.[7]

The girls’ older sister, Leah, decided to take Kate home with her to Rochester, to see if separating the two girls would end the disturbances, but the rapping continued both at the Fox’s home and Leah’s. So Leah decided to abandon her old home, maintaining it might be haunted, and moved to a newer one nearby; Maggie joined them the following day, as planned.[8]

The Fox sisters began public demonstrations of their supposed ability to communicate with the dead in November 1849,[9] and as news of their exploits spread, they began charging for their séances. They launched their first professional tour in 1850, and became national celebrities after their appearances in New York.[10] Many other mediums emerged in the wake of the Fox sisters’ visits, forging a movement based on the belief in spirit communication. Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, coined the term “modern Spiritualism” for the new movement, calling its “tens of thousands” of believers “Spiritualists”.[11]

Interest in Spiritualism waned in the late 1850s,[3] but was rekindled in the aftermath of the American Civil War (1861–1865), during which an estimated 750,000 soldiers were killed,[12] as bereaved families attempted to communicate with the spirits of their lost relatives.[3] The enormous battlefield casualties of the First World War (1914–1918) had a similar impact on the public’s interest in Spiritualism.[13]

Confession

In 1888 Maggie Fox announced in a speech delivered at the New York City Academy of Music that the spirits of the dead never return to communicate with the living, and the rapping noises by which the spirits allegedly communicated were fake,[14] produced by the sisters cracking their toe joints.[3] But the Spiritualist movement survived the revelation, and Maggie retracted her confession the following year, claiming that she had fallen under the influence of the movement’s enemies. and was under severe financial pressure.[14]

Propagation

The Spiritualist movement spread rapidly, particularly in England, where the first Spiritualist Church in the UK – The Keighley Spiritualist Church – was founded in Yorkshire in 1853.[15] It also became popular in Europe and Latin America, especially in the form of spiritism, a development by the French educator and author Allan Kardec,[b]Allan Kardec is the pen name of Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail. who incorporated the idea of reincarnation into the Spiritualist canon.[16]

Present day

Spiritualism today resembles any other religion, having almost completely discarded the showmanship associated with the materialising mediums such as Helen Duncan Last person to be imprisoned under the Witchcraft Act 1735, in 1944., the last person to be imprisoned under the Witchcraft Act of 1735

Last person to be imprisoned under the Witchcraft Act 1735, in 1944., the last person to be imprisoned under the Witchcraft Act of 1735 Sometimes dated 1736, an Act of Parliament that repealed the statutes concerning witchcraft throughout Great Britain, including Scotland., who so fascinated early believers including the English author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, inventor of the detective Sherlock Holmes.[17]

Sometimes dated 1736, an Act of Parliament that repealed the statutes concerning witchcraft throughout Great Britain, including Scotland., who so fascinated early believers including the English author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, inventor of the detective Sherlock Holmes.[17]

The Spiritualists’ National Union (SNU), founded in the United Kingdom in 1901, has a membership of about 300 Spiritualist churches and centres across the UK.[18]

Notes

| a | Despite excavations, no body was ever found.[7] |

|---|---|

| b | Allan Kardec is the pen name of Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail. |