Wikimedia Commons

The Turn of the Screw is an 1898 horror novella by Henry James. It first appeared in serial format in Collier’s Weekly magazine (January 27 – April 16, 1898), and later that year in the book The Two Magics. Classified as gothic fiction and a ghost story, the novella focuses on a governess who, caring for two children at a remote estate, becomes convinced that the grounds are haunted, culminating in the death of one of the children.

In the century following its publication, The Turn of the Screw became a cornerstone text of academics who subscribed to New Criticism. The novella has had differing interpretations, often mutually exclusive. Many critics have tried to determine the exact nature of the evil hinted at by the story, while others have argued that the brilliance of the novella results from its ability to create an intimate sense of confusion and suspense in the reader.

The novella has been adapted numerous times in radio drama, film, stage and television, including a 1950 Broadway play, and the 1961 film The Innocents.

Publication history

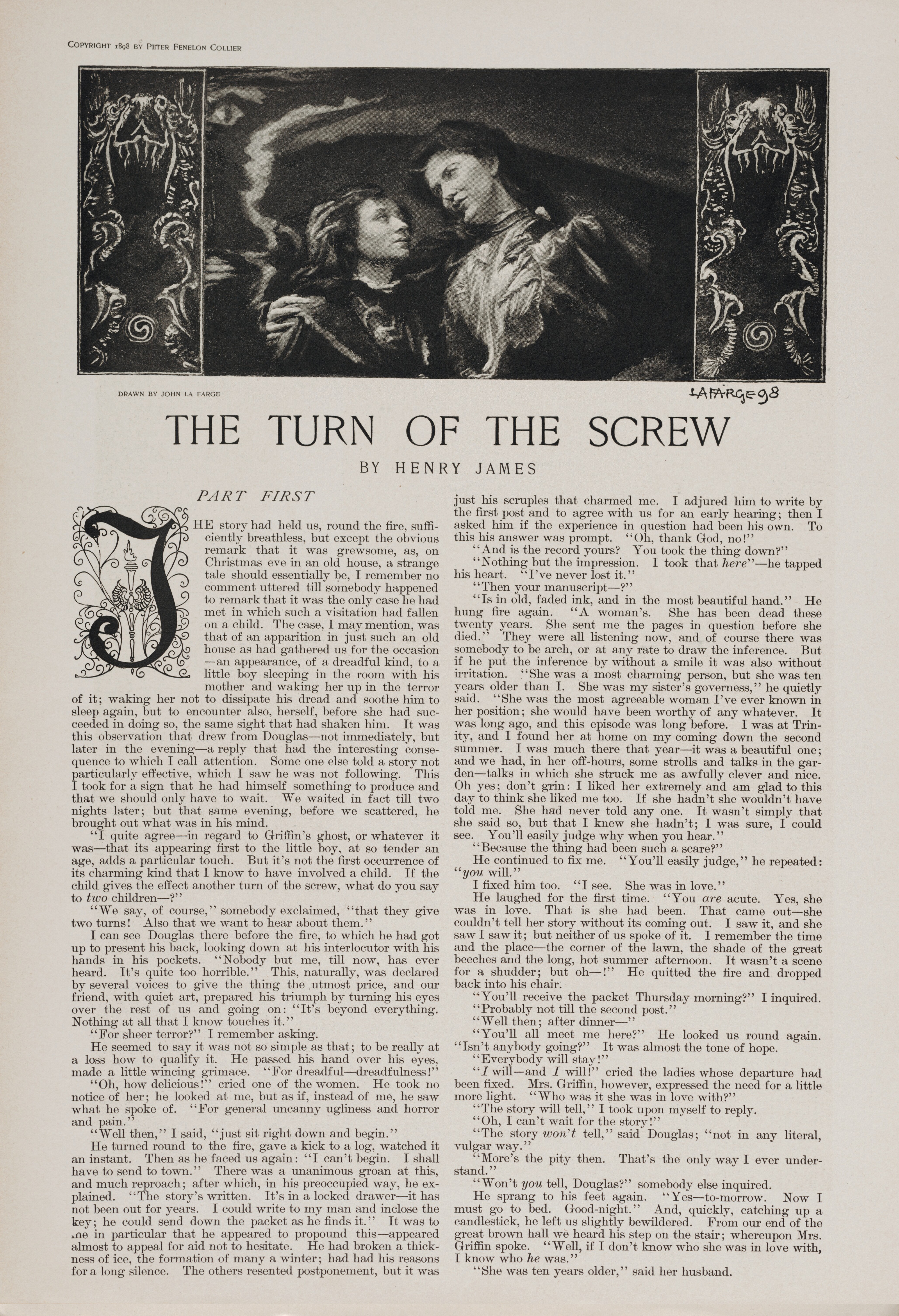

The Turn of the Screw was first published in the magazine Collier’s Weekly, serialised in 12 instalments (27 January – 16 April 1898). The title illustration by John La Farge depicts the governess with her arm around Miles. Episode illustrations were by Eric Pape.[1]

In October 1898 the novella appeared with the short story “Covering End” in a volume titled The Two Magics, published by Macmillan in New York City and by Heinemann in London.[2]

James revised The Turn of the Screw ten years later for his New York Edition.[3] In The Collier’s Weekly Version of The Turn of the Screw (2010), the tale is presented in its original serial form with a detailed analysis of the changes James made over the years. Among many other revisions, James changed the children’s ages.[4]

Plot

On Christmas Eve, an unnamed narrator listens to Douglas, a friend, read a manuscript written by a former governess whom Douglas claims to have known and who is now dead. The manuscript tells the story of how the young governess is hired by a man who has become responsible for his young nephew and niece after the deaths of their parents. He lives mainly in London but also has a country house, Bly. He is uninterested in raising the children.

The boy, Miles, is attending a boarding school, while his younger sister, Flora, is living at a summer country house in Essex. She is currently being cared for by Mrs. Grose, the housekeeper. Miles and Flora’s uncle, the governess’ new employer, gives her full charge of the children and explicitly states that she is not to bother him with communications of any sort. The governess travels to her new employer’s country house and begins her duties.

Miles soon returns from school for the summer just after a letter arrives from the headmaster stating that he has been expelled. Miles never speaks of the matter, and the governess is hesitant to raise the issue. She fears there is some horrible secret behind the expulsion but is too charmed by the adorable young boy to want to press the issue. Soon thereafter, around the grounds of the estate, the governess begins to see the figures of a man and woman whom she does not recognise. These figures come and go at will without ever being seen or challenged by other members of the household, and they seem to the governess to be supernatural. She learns from Mrs. Grose that the governess’ predecessor, Miss Jessel, and another employee, Peter Quint, had had a sexual relationship. Before their deaths, Jessel and Quint spent much of their time with Flora and Miles, and this fact has grim significance for the current governess when she becomes convinced that the two children are secretly aware of the ghosts’ presence.

Later, without permission, Flora leaves the house while Miles is playing music for the governess. The governess notices Flora’s absence and goes with Mrs. Grose in search of her. They find her in a folly on the shore of the lake, and the governess is convinced that Flora has been talking to the ghost of Miss Jessel. When the governess finally confronts Flora, the girl denies seeing Miss Jessel and demands never to see the governess again. At the governess’ suggestion, Mrs. Grose takes Flora away to her uncle, leaving the governess with Miles, who that night at last talks to her about his expulsion; the ghost of Quint appears to the governess at the window. The governess shields Miles, who attempts to see the ghost. The governess tells Miles he is no longer controlled by the ghost and then finds that Miles has died in her arms, and the ghost has gone.

Major themes

Throughout his career James was attracted to the ghost story, although he was not fond of literature’s stereotypical ghosts. He preferred to create ghosts that were eerie extensions of everyday reality, “the strange and sinister embroidered on the very type of the normal and easy”, as he put it in the New York Edition preface to his final ghost story, “The Jolly Corner”.

With The Turn of the Screw, many critics have wondered if the “strange and sinister” were only in the governess’s mind and not part of reality. The result has been a longstanding critical dispute about the reality of the ghosts and the sanity of the governess. Beyond the dispute, critics have closely examined James’s narrative technique for the story. The framing introduction and subsequent first-person narrative by the governess have been studied by theorists of fiction interested in the power of fictional narratives to convince or even manipulate readers.

The imagery of The Turn of the Screw is reminiscent of gothic fiction. The emphasis on old and mysterious buildings throughout the novella reinforces this motif. James also relates the amount of light present in various scenes to the strength of the supernatural or ghostly forces apparently at work. The governess refers directly to The Mysteries of Udolpho and indirectly to Jane Eyre, evoking a comparison of the governess not only to the character of Jane Eyre, but also to the character of Bertha, the madwoman confined in Thornfield.[5]

Literary significance and criticism

Oliver Elton wrote in 1907 that “There is … doubt, raised and kept hanging, whether, after all, the two ghosts who can choose to which persons they will appear, are facts, or delusions of the young governess who tells the story.”[6] Edmund Wilson was another of the earlier proponents of the theory questioning the governess’s sanity, positing sexual repression as a cause for her experiences.[7] Wilson eventually recanted his opinion after considering the governess’s point-by-point description of Quint. Then John Silver[8] pointed out hints in the story that the governess might have gained previous knowledge of Quint’s appearance in non-supernatural ways. This induced Wilson to return to his original opinion that the governess was delusional and that the ghosts existed only in her imagination.

William Veeder sees Miles’s eventual death as induced by the governess. In a complex psychoanalytic reading, Veeder concludes that the governess expressed her repressed rage toward her father and toward the master of Bly on Miles.[9]

Other critics, however, have strongly defended the governess. They note that James’s letters, his New York Edition preface, and his Notebooks contain no definite evidence that The Turn of the Screw was intended as anything other than a straightforward ghost story, and James certainly wrote ghost stories that did not depend on the narrator’s imagination. For example, “Owen Wingrave” includes a ghost that causes its title character’s sudden death, although no one actually sees it. James’s Notebooks entry indicates that he was inspired originally by a tale he heard from Edward White Benson, the archbishop of Canterbury. There are indications that the story James was told was about an incident in Hinton Ampner, where in 1771 a woman named Mary Ricketts moved from her home after seeing the apparitions of a man and a woman, day and night, staring through the windows, bending over the beds, and making her feel that her children were in danger.[10]

In a 2012 commentary in The New Yorker, Brad Leithauser gave his own perspective on the different interpretations of James’s novella:

According to Leithauser, the reader is meant to entertain the propositions that the governess is mad and that the ghosts really do exist, and consider the dreadful implications of each.

Poet and literary critic Craig Raine, in his essay “Sex in nineteenth-century literature”, states quite categorically his belief that Victorian readers would have identified the two ghosts as child molesters.[1]

Film, stage, television adaptations

The Turn of the Screw has been the subject of numerous adaptations and reworkings in a variety of media, and these reworkings and adaptations have, themselves, been analysed in the academic literature on Henry James and neo-Victorian culture. It was adapted to an opera by Benjamin Britten, which premiered in 1954,[12] and the opera has been filmed on numerous occasions.[13] The novella was adapted as a ballet score (1980) by Luigi Zaninelli,[14] and separately as a ballet (1999) by Will Tucket for the Royal Ballet.[15] Harold Pinter directed The Innocents (1950), a Broadway play which was an adaptation of The Turn of the Screw, [16] and a subsequent stage play, adapted by Rebecca Lenkiewicz was presented in a co-production with Hammer at the Almeida Theatre, London, in January 2013.[17]

There have been numerous film adaptations of the novel.[14] The critically acclaimed The Innocents (1961), directed by Jack Clayton, and Michael Winner’s prequel The Nightcomers (1972) are two particularly notable examples.[12] Other feature film adaptations include Rusty Lemorande’s 1992 eponymous adaptation (set in the 1960s)[13]; Eloy de la Iglesia’s Spanish-language Otra vuelta de tuerca (The Turn of the Screw, 1985);[14] Presence of Mind (1999), directed by Atoni Aloy; and In a Dark Place (2006), directed by Donato Rotunno[13]. In 2018, director Floria Sigismondi filmed an adaptation of the novella, called The Turning, on the Kilruddery Estate in Ireland.[18]

Television films have included a 1959 American adaptation as part of Ford Startime directed by John Frankenheimer and starring Ingrid Bergman;[13][19] the West German Die sündigen Engel (The Sinful Angel, 1962),[20] a 1974 adaptation directed by Dan Curtis, adapted by William F. Nolan;[13] a French adaptation entitled Le Tour d’écrou (The Turn of the Screw, 1974); a Mexican miniseries entitled Otra vuelta de tuerca (The Turn of the Screw, 1981);[20] a 1982 adaptation directed by Petr Weigl;[21] a 1990 adaptation directed by Graeme Clifford; The Haunting of Helen Walker (1995), directed by Tom McLoughlin; a 1999 adaptation directed by Ben Bolt;[13] a low-budget 2003 version written and directed by Nick Millard; the Italian-language Il mistero del lago (The Mystery of the Lake, 2009); and a 2009 BBC film adapted by Sandy Welch, starring Michelle Dockery and Sue Johnston.[20]