William Harrison Ainsworth (4 February 1805 – 3 January 1882) was an English historical novelist. Born at King Street in Manchester, he trained as a lawyer, but the legal profession held no attraction for him. While completing his legal studies in London he met the publisher John Ebers, who introduced him to literary and dramatic circles and to his daughter Fanny, who became Ainsworth’s wife.

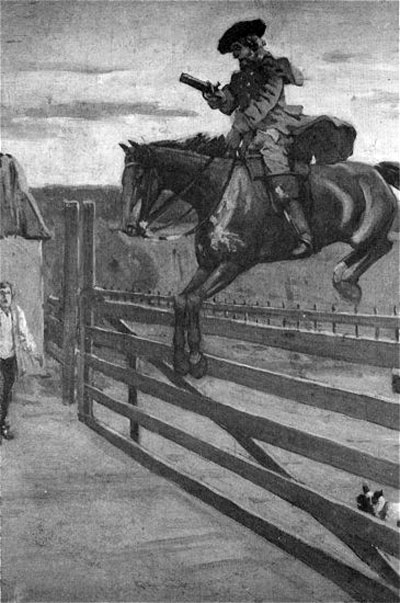

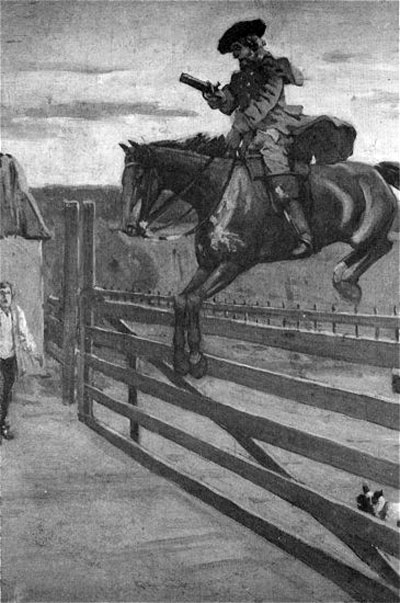

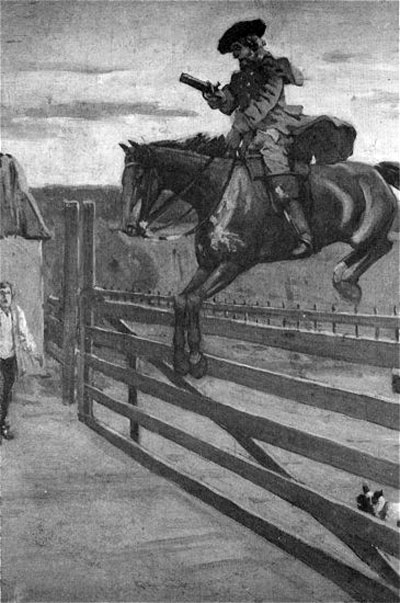

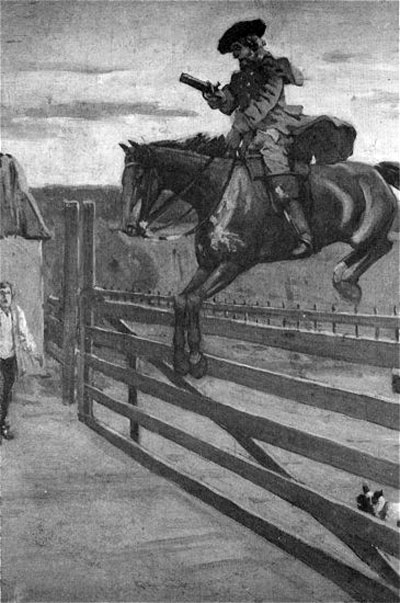

Ainsworth briefly entered the publishing business himself, in partnership with Ebers, but soon gave it up and turned his attention to journalism and literature. His first success as a writer came with Rookwood in 1834, which features Dick Turpin

English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. In the popular imagination he is best remembered for a fictional 200-mile ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess.

English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. In the popular imagination he is best remembered for a fictional 200-mile ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess. as its leading character. A stream of thirty-nine novels followed, the last of which, Stanley Brereton, appeared in 1881. A particular feature of Ainsworth’s novels is their attention to historical detail, but with the introduction of supernatural elements characteristic of the Gothic tradition

In the 1840s Ainsworth was considered to be a serious rival to Charles Dickens, but later in life his popularity waned, as his style of historical romances became unfashionable. Sales of his work declined throughout the 1860s, and efforts at branching out into other genres such as the autobiographical Mervyn Clitheroe (1851, 1857) proved to be unsuccessful.

Ainsworth died at his home in Reigate on 3 January 1882, and was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. A few months earlier, Ainsworth had been the guest of honour at a banquet hosted by the mayor of Manchester, at which he was lauded as the “Lancashire novelist” for depicting his native county in a series of novels spanning four hundred years of the county’s history.

Early life

Ainsworth was born on 4 February 1805 in the family home at 21 King Street, Manchester, to Thomas Ainsworth, a prominent Manchester lawyer, and Ann (Harrison) Ainsworth, the daughter of the Rev. Ralph Harrison, the Unitarian minister at Manchester Cross Street Chapel.[1] He was home-tutored until the age of twelve, before attending Manchester Free Grammar School from 1817 to 1822. During that time Ainsworth produced his first known published work, under the pseudonym T. Hall, a composition in rhymed couplets entitled “The Rivals: a Serio-Comic Tragedy”, printed in Arliss’s Pocket Magazine in 1821. The following year Ainsworth’s first book, Poems, was published under the pseudonym Cheviot Ticheburn.[2]

In accordance with his father’s wishes, in the early 1820s Ainsworth became articled as a clerk to a Manchester solicitor, Alexander Kay. Following his father’s death in 1824, Ainsworth inherited his father’s law practice. After further training at the chambers of Jacob Phillips at the Inner Temple in London, Ainsworth qualified as a solicitor in 1826, but the law held little interest for him. That same year he ventured into the publishing business with John Ebers, manager of the Italian Opera House, and who had published Ainsworth’s first novel, Sir John Chiverton (1826), written jointly with J. P. Aston. 1826 was clearly an eventful year for Ainsworth, as on 11 October he married Anne Frances (Fanny) Ebers (1804/5–1838), his business partner’s daughter.[2]

The publishing venture with Ebers did not work out well for Ainsworth, and he withdrew from it in 1829, after which he spent some time travelling in Europe before returning briefly to the law the following year.[2]

Literary career

Ainsworth’s first novel, Rookwood (1834), was an immediate success, depicting the legendary ride of the highwayman Dick Turpin

English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. In the popular imagination he is best remembered for a fictional 200-mile ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess.

English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. In the popular imagination he is best remembered for a fictional 200-mile ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess. from London to York, which became accepted by many as historical fact despite it being his own invention.[2] Rookwood went through several editions, and the success of the fifth, which appeared in 1837, encouraged Ainsworth to begin work on a novel about another famous outlaw, Jack Sheppard.[3]

Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard was published in serial form in Bentley’s MiscellanyIllustrated monthly magazine published from 1837 until 1868. from January 1839 until February 1840, then edited by Charles Dickens. Dickens’s Oliver Twist also ran in the magazine between 1837 and 1839,[4] and the two men became embroiled in a moral panic that became known as the Newgate ControversyEarly form of sensation literature, drawing its inspiration from the Newgate Calendar, first published in 1773 and containing biographies of famous criminals.. The middle classes were becoming anxious about the rising crime rate, and the possibility that stories apparently glorifying criminals might tempt impressionable working-class boys into a life of crime. According to the literary historian Steven Carver, the stigma surrounding Jack Sheppard poisoned everything Ainsworth subsequently wrote. Dickens on the other hand kept his head down until 1841, when he argued persuasively in the preface to that year’s edition of Oliver Twist that it was “a work of social realism not a jaunty criminal romance”.[5]

In the aftermath of the Newgate Controversy, Ainsworth turned his attention to historical novels, including Guy Fawkes (1840), The Tower of London (1840), and Old Saint Paul’s (1841) But as his style of historical romances became increasingly unfashionable, he attempted to adopt other forms, such as the autobiographical Mervyn Clitheroe (1851, 1857), but with little success. Returning to his historical novels, he found himself forced to write at an increasing pace for decreasing remuneration.[2] Writing about Ainsworth’s decline, the literary critic and journalist John Sutherland has commented that “Many would have backed Ainsworth’s talent against Dickens’s in 1840. In the 1860s Dickens was earning £10,000 a novel, Ainsworth a hundredth of that sum.”[6]

Ainsworth’s Magazine

Ainsworth took over the editing of Bentley’s Miscellany from Dickens in 1839, but left at the end of 1841 to begin his own publication, Ainsworth’s Magazine. The first issue was published on 29 January 1842 and featured Ainsworth’s The Miser’s Daughter, illustrated once again by Cruikshank.[7][8] Ainsworth’s next novel, Windsor Castle, ran in the magazine from July 1842 until June 1843.[9]

By the end of 1843, Ainsworth had sold his stake in Ainsworth’s Magazine to John Mortimer, but he remained as editor.[10] Publication ceased in 1854, when Ainsworth returned to Bentley’s after having purchased it for £1700.[2]

Later life

After moving from London to Brighton in 1853, Ainsworth became more and more reclusive, but in 1856 he did receive public recognition in the form of an annual civil-list pension of £100, equivalent to about £9000 as at 2019.[a]Using the Retail Price index.[11] Ainsworth had separated from his first wife Fanny in 1835, and she died three years later. In 1866 he married Sarah Wells, with whom he had one daughter.[2]

Ainsworth died at his home in Reigate on 3 January 1882, and was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.[2]

Critical reception

Ainsworth was largely forgotten by critics after his death. In 1911 the biographer S. M. Ellis commented: “It is certainly remarkable that, during the twenty-eight years which have elapsed since the death of William Harrison Ainsworth, no full record has been published of the exceptionally eventful career of one of the most picturesque personalities of the nineteenth century.”[12] Even at the height of his popularity critics accused Ainsworth of producing historical “picture books” lacking in seriousness, and generally of interest only to boys.[2]

Historians have been critical of the mingling of fact and fiction in Ainsworth’s novels, noting that his romanticised depiction of Dick Turpin became rapidly accepted as historical fact. Similarly, he distorted the events surrounding the 1612 Lancashire witch trials

The trials of the Pendle witches in 1612 are among the most famous witch trials in English history, and some of the best recorded of the 17th century., turning the story into a Gothic romance in his novel The Lancashire WitchesNovel by William Harrison Ainsworth, first published in 1848. Based on the true story of the Pendle witches, it is the only one of his forty novels that has never been out of print. (1848).[13] Writing in 1986, the bibliographer Everett Franklin Bleiler offered his opinion that “All in all, Ainsworth was not a great writer – his contemporaries included men and women who did things better – but he was a clean stylist and his work can be entertaining”.[14]

See also

- William Harrison Ainsworth bibliography

Works of William Harrison Ainsworth (1805–1882) listed in order of their date of first publication.