William Hulton (23 October 1787 – 30 March 1864) was a landowner and magistrate who lived at Hulton Hall near Westhoughton in Lancashire, the estate his family had owned since the late 12th century. His family wealth was built on the coal under the estate that was developed particularly after the construction of the Bolton and Leigh RailwayLancashire's first public railway, promoted as a mineral line in connection with William Hulton's coal pits to the west of his estate at Over Hulton. .

Hulton became notorious for two events: the execution of four Luddites who set alight a factory in Westhoughton and as Chairman of the Lancashire and Cheshire Magistrates who ordered the local yeomanry to disperse the crowd at a reform meeting that caused the deaths of fifteen people in what became known as the Peterloo MassacreCavalry charge on 16 August 1819 into a crowd of 60,000–80,000 gathered at St Peter's Field, Manchester, England to demand the reform of parliamentary representation .

Life

William Hulton was the second son of William Hulton and Jane (née Brooke). His father, who enjoyed hunting and horseracing at Kersal Moor, was High Sherrif of Lancashire in 1789. When his father died in 1800, William Hulton was 12 years old.[1] He matriculated in 1804 and proceeded to Brasenose College, Oxford where he was awarded M. A. in 1807. On attaining his majority in 1808, Hulton took charge of the estate and married his cousin, Maria Ford. Together they had thirteen children, ten of whom survived to maturity.[2]

Hulton died on 30 March 1864 at Leamington Priors in Warwickshire and was buried on 5 April 1864 at St Mary’s Church in Deane, not far from his estate near Bolton.

Politics, Luddites and Peterloo

Politically, Hulton was a Tory whose hero was William Pitt the Younger. In 1811, aged 24, Hulton was appointed High Sheriff of Lancashire and was made a Justice of the Peace.[2] The following year Luddites[a]groups of English textile workers who, between 1811 and 1816, destroyed the machinery in cotton and woollen mills that they believed was threatening their jobs set fire to Rowe and Dunscough’s Mill in Westhoughton. Twelve protesters were arrested. Hulton testified that one, aged 15, was honest and industrious and was acquitted but four who were sent for trial including a boy aged twelve, were hanged outside Lancaster Castle. It is likely that his colleague, Colonel Fletcher of Bolton, may have taken advantage of Hulton’s inexperience at his “grim introduction” to the Justiceship.[3]

In 1819 Hulton was made chairman of the Lancashire and Cheshire Magistrates, a committee set up to deal with the civil unrest endemic in the area. It was Hulton who summoned the local Yeomanry to deal with the large crowd in St Peter’s Square in Manchester on 16 August 1819 that had gathered to hear the radical political agitator Henry Hunt.[4]

Hulton, watching from a house on the edge of St Peter’s Field, saw the enthusiastic reception Hunt received on his arrival. He issued an arrest warrant for Hunt, Joseph Johnson, John Knight, and James Moorhouse. The Chief Constable said that the press of the crowd surrounding the hustings would make military assistance necessary. Hulton then wrote two letters, one to Major Thomas Trafford, commanding the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry, and the other to the military commander in Manchester, Lieutenant Colonel Guy L’Estrange. The contents of both notes were similar:[4]

— Letter sent by William Hulton to Major Trafford of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry

The Yeomanry, on horseback with sabres drawn, forced their way through the crowd to allow Hunt to be arrested. Hulton perceived the events as an assault on the yeomanry, and when L’Estrange and his hussars arrived, he ordered them to disperse the crowd with the words: “Good God, Sir, don’t you see they are attacking the Yeomanry; disperse the meeting!” Fifteen people died from sabre and musket wounds or trampling and 400 to 500 were injured.[6]

Lord Sidmouth, the Home Secretary, conveyed the kings’s satisfaction at Hulton’s “prompt, decisive and efficient measures” but his reputation was forever tainted among the working classes who nicknamed him, “old Peterloo”.[7] Hulton was vilified by the local population and was obliged to decline a safe parliamentary seat offered to him in 1820. The bad feeling continued and in 1841 Hulton and his family were attacked during an election campaign in Bolton.[7]

Hulton’s great-great-great grandson, the Conservative peer and screenwriter, Julian Fellowes, considers that his ancestor was “was clearly terrified of any overthrow of the established social order.” He describes Hulton’s heavy-handed response to the events at St Peter’s Field as a total misreading of the situation. “It was only the barest of beginnings for any kind of workers’ movement, but Hulton immediately went into some kind of overdrive, attacking a group that included a group of many women and many children – a lot of whom hadn’t done anything.”[8]

Coal

Wikimedia Commons

The Hulton fortune was built on coal under the Hulton Park estate and Hulton who owned mineral rights in surrounding townships developed the collieries.[7] Hulton only ceased paying his workforce with tokens or vouchers that could only be redeemed in his company shop in 1831, when the practice was outlawed by the passing of the Truck Act.[9]

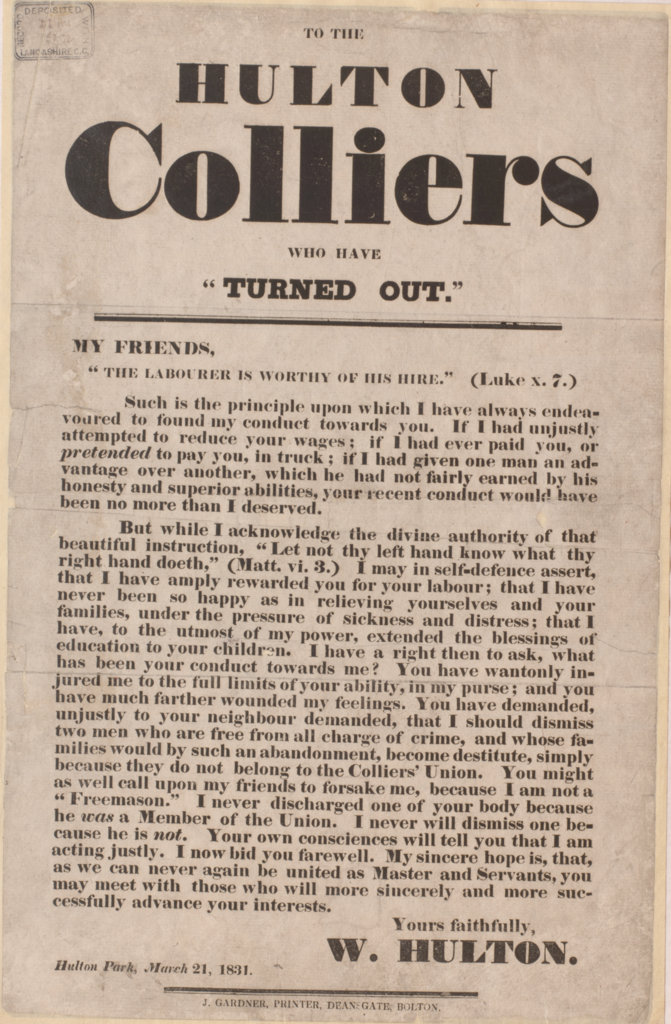

In 1831 Hulton’s colliers struck for the right to be members of a union and demanded an increase in wages. Hulton’s response was to issue a handbill explaining that the men were “amply rewarded” and that they had “wantonly injured” him “in his purse”. [10]

David Swallow, general secretary of the Miners’ Association, said in 1843 that Hulton’s colliers were the poorest paid in Lancashire. When Swallow visited Westhoughton, Hulton and other local coal owners persuaded the local publicans to prevent him. from holding meetings in their premises and paid for beer to keep their miners away from the union. Hulton threatened Swallow with prison if he held an outdoor meeting.[11] Hulton still did not wish to see free assembly of working men.[10]

In 1858, in partnership with Harwood Walcot Banner, Hulton founded the Hulton Colliery CompanyThe Hulton Colliery Company operated on the Lancashire Coalfield from the mid-19th century in Over Hulton and Westhoughton, Lancashire.. From 1868 onwards the company traded under the Hulton name. It became a limited liability company in 1886 when the Hultons relinquished direct control.[7]

Bolton and Leigh Railway

Hulton was a major supporter and promoter of the Bolton and Leigh Railway, the first public railway in Lancashire. It passed close to the west of his estate and enabled him to sell coal from his pits to Bolton, Manchester and Liverpool. George Stephenson stayed at Hulton Hall for several months while the railway way being planned and built. The northern section of the line was opened on 1 August 1828, witnessed by 40,000 people.[7]