Worsley’s third manor house, New Hall was built in Worsley near Manchester in 1846 to designs by Edward Blore for Francis Egerton, 1st Earl of Ellesmere. It replaced the Georgian Brick Hall built in 1760 by the Duke of Bridgewater. New Hall and its gardens were neglected and fell into disrepair after 1914 when the 4th Earl lent New Hall to the British Red Cross as a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) hospital.[a]The Voluntary Aid Detachment was a unit of civilians who provided nursing care for military personnel in the United Kingdom and throughout the British Empire. The Egertons never returned after the war, and the hall’s contents were dispersed or sold by the then earl. Bridgewater Estates bought the hall in 1923. The hall and part of the site were requisitioned by the War Office in 1939 and used for training troops. The hall was badly damaged by fire in 1943 and demolished in 1949.

The site was acquired by the Peel Group in the 1980s. Peel announced that in collaboration with Salford Council and the Royal Horticultural Society, the garden would be renovated as RHS Garden BridgewaterThe Royal Horticultural Society's first new garden since 2003, opening in 2020 in Worsley, in the City of Salford.The Royal Horticultural Society's first new garden since 2003, opening in 2020 in Worsley, in the City of Salford..

Background

After Francis Egerton, who became the 3rd Earl of Ellesmere, inherited the Worsley estate in 1833, architect Edward Blore made alterations to the Old Hall, designed the Garden Cottage, and between 1839 and 1845, designed the Bridgewater Trust Offices in Walkden. He specialised in Tudor and Elizabethan styles and most of his clients were from the gentry and peerage. Blore completed the remodelling of Buckingham Palace after John Nash was dismissed in 1831.[1]

History

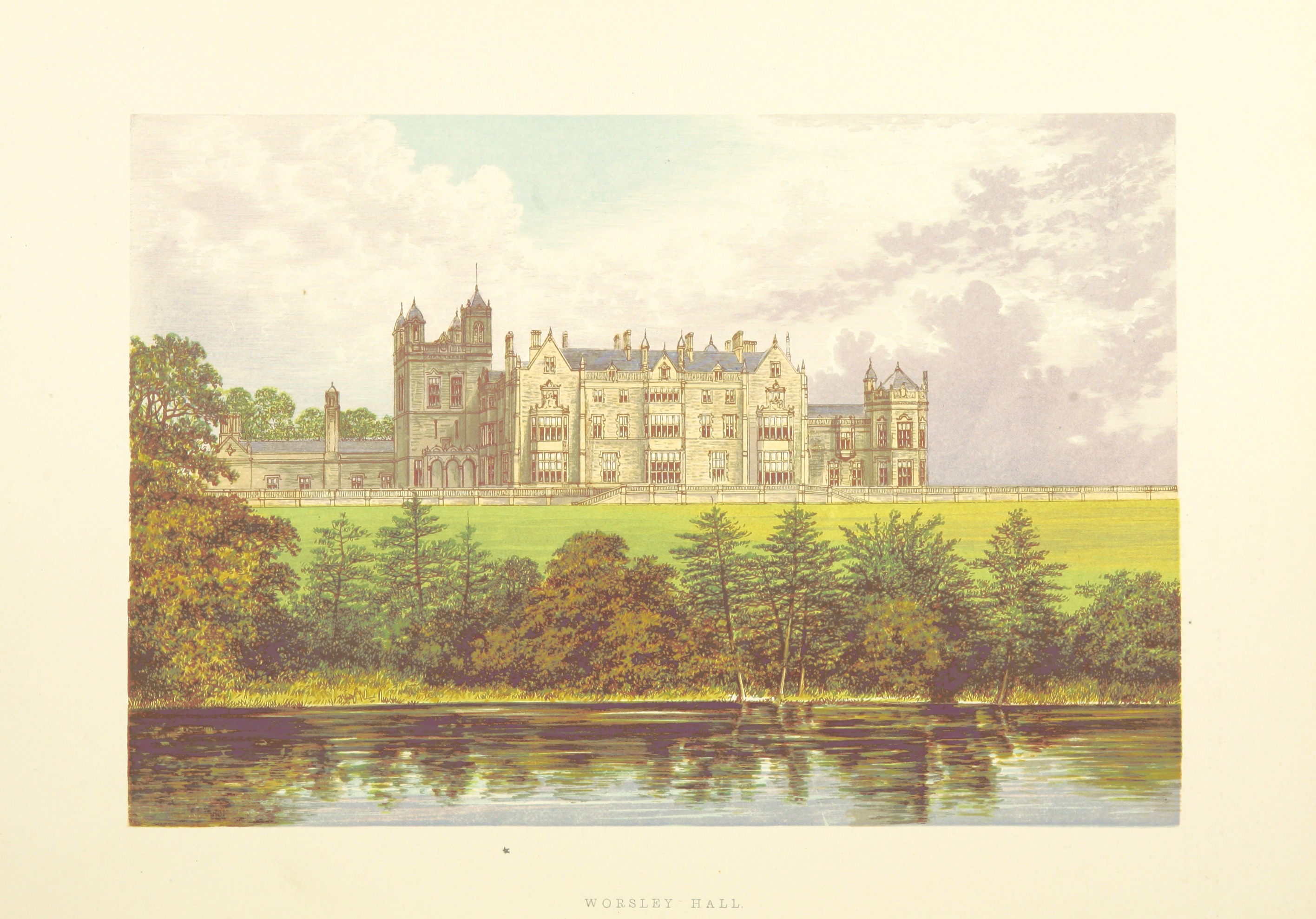

Blore designed Worsley New Hall for the 3rd Earl in the Elizabethan Gothic style. It replaced the Brick Hall that was built in the 1760s for the 3rd Duke of Bridgewater.[1] Brick Hall was built because the timber-framed old hall, which is still standing, was considered to be too small.[2] Work began on the new hall in 1839 and was completed in 1846 and Brick Hall was demolished as the work neared completion. The new hall costing £100,000, one of Blore’s biggest houses, was built from Hollington stone brought from Staffordshire. Its symmetrical main block was three storeys high and had a family wing on one side and a tower and servant wing on the other.[1]

Queen Victoria visited the hall twice, in 1851 and 1857.[1]

After the death of the 3rd earl in 1914, the hall passed to his to his son, the 4th Earl but the Egertons never lived again at New Hall. When war broke out in 1914, he lent the hall to the British Red Cross as a VAD Hospital. It was fitted out to accommodate up to 132 patients. The rooms were converted into wards, sitting and dining rooms, and the gardens and boating lake were used for recreation. The kitchen gardens provided fruit and vegetables. The hospital closed in 1919, but the Egerton family struggled with its upkeep. Death duties led the 4th Earl to sell items of furniture and fittings at auction and other items were moved to his other properties. In 1923 the Worsley estate including the hall was sold to Bridgewater Estates for £3,300,000.[1]

Parts of the site were requisitioned by the War Office at the start of World War II. The 2nd/8th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers used the hall and gardens as a training ground in 1939 and 1940. After they left, the 42nd and 45th County of Lancaster Battalions of the Home Guard moved in.[2] The hall fell into disrepair, the gardens were overgrown, and while occupied by the military, the entrance gates on Leigh Road were damaged, windows smashed and interior fittings used for firewood. In September 1943 the hall’s top floor was seriously damaged by fire. By then the hall was weakened by dry rot and mining subsistence. Tenders to demolish it were put out in 1944. It was sold to a scrap merchant who demolished it in 1946.[1]

In 1951 the War Department requisitioned part of the site where the servant’s wing stood to build a reinforced concrete bunker and erect two radar masts for anti-aircraft operations. In 1956 the Department purchased the bunker site and from 1958 to the early 1960s, it was used by the Royal Navy as a food store. The bunker was sold to Salford Corporation for use as a joint area control centre with Lancashire County Council in 1961. After the Civil Defence Corps was disbanded in 1968 it was handed to the Greater Manchester Fire Service and in 1985 leased to a local gun club.[1]

The Peel Group acquired the site and sought to develop it and rejuvenate the gardens. After archaeological digs and funding research, a detailed history of the site was compiled.[1][3]

In 2015 the Royal Horticultural Society announced that in collaboration with the landowners, Peel, and Salford Council, it planned to open its fifth garden, RHS Garden BridgewaterThe Royal Horticultural Society's first new garden since 2003, opening in 2020 in Worsley, in the City of Salford.The Royal Horticultural Society's first new garden since 2003, opening in 2020 in Worsley, in the City of Salford. on the site of the derelict gardens.[4] The garden opened a year later than planned, on 17 May 2021.[5]

Gardens

The walled garden preceeded the construction of New Hall.[1] William Andrews Nesfield, the country’s most sought after landscape designer, was involved in laying out the gardens from 1846.[1]

The Gardener’s Chronicle described the New Hall and its grounds in 1846:

— The Gardeners Chronicle

A terraced garden was constructed on sloping ground to the south of the hall. Six terraces separated by stone balustrades were accessed by steps and gravel paths. Nesfield designed the two upper terraces in intricate patterns based on 17th-century French embroidery designs. The French company, Val d’Osne erected a bronze fountain in the centre and with two more fountains in the terraced gardens was fed from Blackleach reservoir.[1]

Landscaped parkland extended to the south towards a lake with an island accessed by a footbridge. A croquet lawn and tennis court were built near the terraces. THe Bridgewater Canal skirted the estate to the south. Woodland west of the hall separated its grounds from the gardener’s cottage and kitchen gardens. The kitchen garden provided flowers, fruit and vegetables for the hall. Flowers and evergreens were given to decorate local churches at Christmas and Easter. By the late 19th century the wall that surrounded the kitchen garden was heated with flues to ward off the effects of frost. The kitchen garden covered around 10 acres and had potting sheds and glasshouses used to grow peaches, grapes, melons and cucumbers.[1][2]

Garden Cottage was built in 1834 to accommodate the estate’s head gardener. The Bothy was built as living accommodation for unmarried gardeners whose job was to stoke the boiler in the cellar that heated the glasshouses. Garden Cottage and the Bothy are still standing. William Upjohn, the head gardener for more than 40 years retired in 1914 and remained at Garden Cottage until 1939. It was then leased by Bridgewater Estates until 1948 when it was sold to Richard and Herbert Cunliffe, who used it as an office and dwelling for Worsley Hall Nurseries and Garden Centre.[1]

Notes

| a | The Voluntary Aid Detachment was a unit of civilians who provided nursing care for military personnel in the United Kingdom and throughout the British Empire. |

|---|