Joseph Noel Paton (13 December 1821 – 26 December 1901) was a Scottish artist, illustrator, poet and sculptor. He had a deep-seated interest in, and knowledge of, Scottish folklore and Celtic legends, which he made use of in his paintings. Despite working in the style of the Pre-RaphaelitesGroup of English artists formed in 1848 to counter what they saw as the corrupting influence of the late-Renaissance painter Raphael., he rejected an invitation to formally join the brotherhood.

As a sculptor, Paton faced controversy concerning his design for the proposed Wallace Monument in Stirling. Initially his submission was selected as the successful model, but the offer to use his design was withdrawn following a public outcry.

A keen collector of armour and weaponry, Paton inherited his father’s compendium of relics from the museum maintained in his childhood home at Wooer’s Alley. Open to the public, visitors to the cottage were able to view an eclectic mix of items ranging from furniture previously owned by royal households through to paraphernalia associated with witchcraft.

Personal life and education

Paton was born in Wooer’s Alley, Dunfermline, Fife on 13 December 1821,[1] to Joseph Neil PatonDamask designer and antiquarian with large collection containing witchcraft objects, including the skull of Lilias Adie. Father of the artist Joseph Noel Paton. and Catherine MacDiarmid, damask designers and weavers in the town.[2] His older sibling was the sculptor Amelia Robertson Hill, and his younger brother was the landscape artist Waller Hugh Paton.[3]

After attending Dunfermline School and then Dunfermline Art Academy, further enhancing the talents he had developed as a child,[1] Paton followed the family trade by working as the design department director in a muslin factory for three years.[1][3] Most of his life was spent in Scotland,[3] but in 1843 he studied briefly at the Royal Academy in London,[2] where he was tutored by George Jones.[4]

On 17 June 1858 Paton married Margaret Gourlay Ferrier, with whom he had eleven children: seven sons and four daughters.[3] Their eldest son, Diarmid Noel Paton (1859–1928), became a regius professor of physiology in Glasgow in 1906; another son, Frederick Noel Paton (1861–1914[5]), also a noted illustrator, was appointed director of commercial intelligence to the government of India in 1905.[2][5]

Career

Paintings and illustrations

While studying in London Paton met John Everett Millais,[6] who asked him to join the Pre-Raphaelite BrotherhoodGroup of English artists formed in 1848 to counter what they saw as the corrupting influence of the late-Renaissance painter Raphael..[1] Paton declined,[1] although he painted in the Pre-Raphaelite style and became a painter of historical, fairyGenre of art and illustration featuring small imaginary human-like creatures with magical powers, often with wings., allegorical and religious subjects.[7] Together with Daniel Maclise, Paton was a folklore expert;[8] according to Christopher Wood, an expert in Victorian art,[9] Maclise and Paton were the only artists working in the genre of fairy paintings with expertise in folklore.[8] Paton’s knowledge of Celtic legends and Scottish folklore is reflected in his paintings.[6]

While in London, Paton became acquainted with the editor of The Art Journal, Samuel Carter Hall, who commissioned him to design some of the illustrations for his book The Book of British Ballads.[3] Other commissions to design book illustrations included the 1844 edition of Shelley’s lyrical drama Prometheus Unbound, an 1845 publication of Shakespeare’s The Tempest and an 1863 version of Coleridge’s poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.[3]

In 1844 Paton’s first painting, Ruth Gleaning, was exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy.[2] He won a number of prizes for his work including for two of his most famous works The Quarrel of Oberon and TitaniaOil on canvas painting by the Scottish artist Sir Joseph Noel Paton. and The Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania, the latter securing a prize at Westminster Hall in 1847.[4] An earlier study of the Quarrel painting was completed in 1846 and featured as Paton’s diploma picture[10] at the Royal Scottish Academy that year.[11] The Academy purchased the earlier work for £700.[12]

Paton became an associate of the Royal Scottish Academy in 1847 and a fellow in 1850;[4] in 1867 he was appointed Queen’s Limner for Scotland, the same year he received a knighthood. In 1878 he was conferred an honorary LLD doctorate by the University of Edinburgh.[3]

Poetry and sculpture

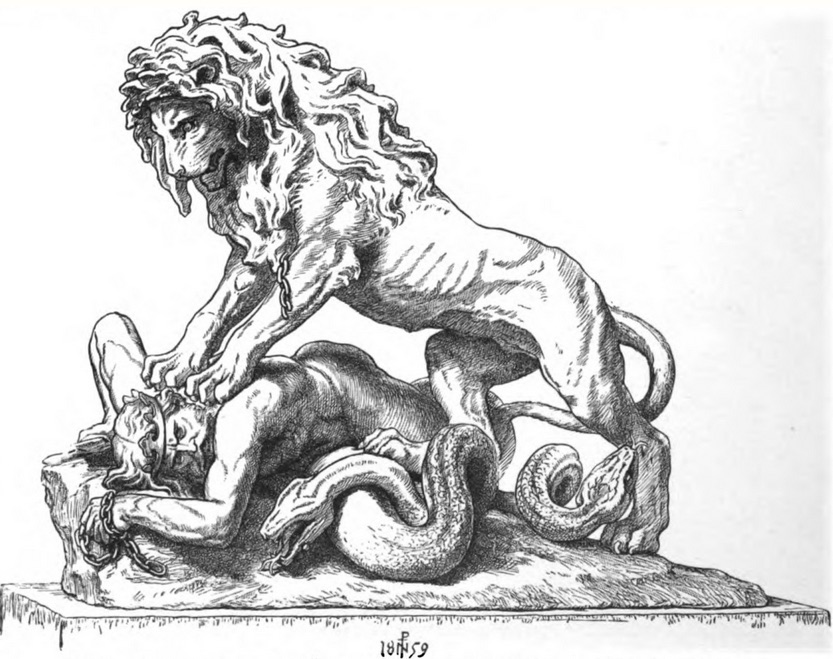

Two volumes of Paton’s poetry were published, Poems by a Painter in 1861 then Spindrift six years later, and several other poems appeared in magazines.[13] He also turned his skills towards sculpture: in January 1859 he submitted a design for the National Wallace Monument. After resigning his post on the committee set up to organise the building of the structure to enable him to compete, his submission was selected but, following strongly voiced public objections, the offer was withdrawn by the Monument executive committee in March.[14]

Antiquary

Paton was a well-known antiquary whose speciality was arms and armour.[2] In 1859 he raised and commanded the 1st Edinburgh (City) Artillery Volunteer Corps, composed mainly of artists, with the painter John Faed as his lieutenant.[15] His father, Joseph Neil Paton, also an avid collector, maintained a museum in his cottage at Wooer’s Alley in Dunfermline to which he allowed the public access. Among the exhibits were a table dated 1310 that had belonged to Robert the Bruce plus other furniture and memorabilia from royal households. The skull of Lilias AdieElderly Torryburn woman who died after confessing to witchcraft; her face was reconstructed from photos of her skull., an elderly woman from Torryburn who died in prison while being interrogated on witchcraft charges, formed part of his collection; further items associated with witches such as a scold’s bridleDevice used to punish women whose language was considered to be unacceptable. and possessions of others convicted of sorcery were also included. These passed to Sir Joseph on his father’s death.[16][17][a]In 2017 a forensic team from the University of Dundee reconstructed the face of Lilias Adie based on photographs taken of the skull before it went missing.[18][19]

Death

Paton died on 26 December 1901 in Edinburgh at his home 33 George Square – where he had lived since 1859 with his wife until her death in 1900 – and is buried in Dean Cemetery.[3]