Joseph Neil Paton (1797–1874) was a damask designer and weaver based in Dunfermline. His wife, Catherine MacDiarmid, was related to the Scottish song writer Carolina NairneScottish songwriter, many of whose songs, such as “Will ye no’ come back again?” and “Charlie is my Darling”, remain popular today, almost two hundred years after they were written. Scottish songwriter, many of whose songs, such as “Will ye no’ come back again?” and “Charlie is my Darling”, remain popular today, almost two hundred years after they were written. , and the couple’s children all went on to become well-known artists themselves. More than seven hundred of Paton’s designs were purchased by the Victoria and Albert museum following his death.

Deeply religious, Paton followed several denominations before adopting the doctrines of the Swedenborgians. He built a chapel beside his house, in which he delivered sermons.

Paton was a passionate collector of artefacts. Ranging from furniture connected to royal households through to a large selection of books, his extensive collection also included curiosities associated with witchcraft.

Personal life

Born in 1797,[1] to a Unitarian father, Paton held strong religious beliefs throughout his lifetime. After initially dabbling with Presbyterianism, he turned to Methodism before embracing the doctrines of the Quakers. He married Catherine MacDiarmid, a folklorist from an old Highland family and a relation of Carolina NairneScottish songwriter, many of whose songs, such as “Will ye no’ come back again?” and “Charlie is my Darling”, remain popular today, almost two hundred years after they were written. Scottish songwriter, many of whose songs, such as “Will ye no’ come back again?” and “Charlie is my Darling”, remain popular today, almost two hundred years after they were written. .[2] The couple had three children: Amelia Robertson, born in 1820; her younger brother, Joseph NoelScottish artist, illustrator, antiquary, poet and sculptor. born a year later in 1821; and their youngest child, Waller Hugh, born in 1828. All three became notable artists.[1][a]Amelia was a sculptor who, at the age of forty-two, married David Octavius Hill (1802–1870);[3] Joseph Noel was an artist; and Waller Hugh, a landscape painter.[1]

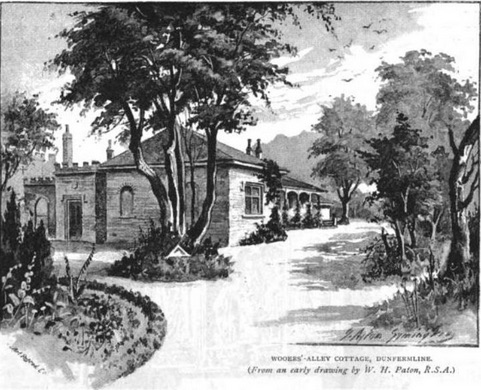

Paton became a Quaker before the birth of his first son, and all the children were tutored by a Quaker governess as youngsters. The family home, a cottage named Wooer’s Alley, in Dunfermline was built by Paton and, later when he turned to the Swedenborgian religious beliefs, he built a small chapel close to the house, in which he preached regularly. One of the ceilings in the cottage was decorated by Robert T. Ross, reflecting works by Old Masters such as Raphael.[4][5]

Career

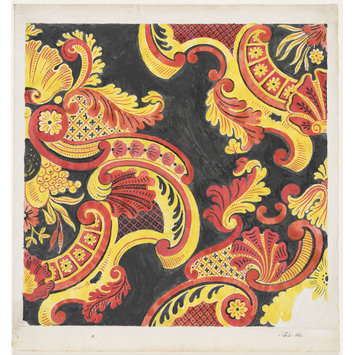

Paton initially studied as a student of art at the Trustees Academy in Edinburgh.[5] Returning to Dunfermline, he commenced weaving linen before returning to Edinburgh, where he served an apprenticeship as a bookbinder. Shortly afterwards he established his successful textile design business based in Dunfermline; his work attracted buyers from firms throughout the UK, but he is predominantly linked to Erskine Beveridge & Co, which in the 1850s became the largest company in the town.[6][b]The factory of Erskine Beveridge & Co was built in 1851; within twenty years it had a staff of fifteen hundred women.[7]

In 1822 Paton won an annual prize for his work in the category for “Designs for table linen”.[8]

Antiquarian

An avid collector of antiquities, Paton maintained a museum in his cottage, Wooer’s Alley, to which he allowed the public access. Among the exhibits were a table dated 1310 that had belonged to Robert the Bruce plus other furniture and memorabilia from royal households. A scold’s bridleDevice used to punish women whose language was considered to be unacceptable. and the skull of Lilias AdieElderly Torryburn woman who died after confessing to witchcraft; her face was reconstructed from photos of her skull., an elderly woman from Torryburn who died in prison while being interrogated on witchcraft charges, also formed part of the collection, along with the possessions of others convicted of witchcraft and sorcery.[9][10][c]In 2017 a forensic team from the University of Dundee reconstructed the face of Lilias Adie based on photographs taken of the skull before it went missing.[11][12]

Death and aftermath

Paton died in his home on 14 April 1874.[13][14] A selection of his collection of antiquities and books together with more than a thousand damask designs were offered for sale at Chapman’s auction in Edinburgh during November 1874.[15] The Victoria and Albert Museum, London, bought more than seven hundred of the designs.[6]

The cottage was auctioned in early April 1875 with a reserve price of twelve hundred pounds. It was purchased by a local merchant.[16]

Notes

| a | Amelia was a sculptor who, at the age of forty-two, married David Octavius Hill (1802–1870);[3] Joseph Noel was an artist; and Waller Hugh, a landscape painter.[1] |

|---|---|

| b | The factory of Erskine Beveridge & Co was built in 1851; within twenty years it had a staff of fifteen hundred women.[7] |

| c | In 2017 a forensic team from the University of Dundee reconstructed the face of Lilias Adie based on photographs taken of the skull before it went missing.[11][12] |