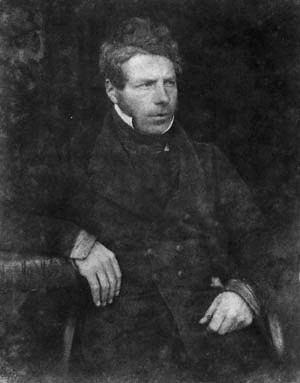

by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson

Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Chambers Book of Days was the last major work produced by the Scottish writer and publisher Robert Chambers (1802–1871).[1] Full title The Book of Days: A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar, Including Anecdote, Biography, & History, Curiosities of Literature and Oddities of Human Life and Character, it was first published in 1864, a mammoth undertaking which, his family believed, hastened his death.[2]

In his preface, Chambers describes the contents of the book:

- Matters connected with the Church Kalendar, including the Popular Festivals, Saints’ Days and Other Holidays, with illustrations of Christian Antiquities in general

- Phenomena connected with the Seasonal Changes

- Folk-Lore of the United Kingdom – namely Popular Notions and Observances connected with the Times and Seasons

- Notable Events, Biographies, and Anecdotes connected with the Days of the Year

- Articles of Popular Archaeology, of an entertaining character, tending to illustrate the progress of Civilisation, Manners, Literature and Ideas in these kingdoms

- Curious, Fugitive, and Inedited Pieces

The book then continues with a series of articles on time, day, month, year and so on, before getting to its heart, a section for each day of the year preceded by a general article on the month itself. The article for January 1, for instance, lists the birth of Edmund Burke and the death of William Wycherley among others, and follows up with detailed articles on both. With about six or seven such articles for each day, the book contains more than 2000 entries, accompanied by illustrations.

Updated edition

The publishing house that still bears Chambers’ name, Chambers Harrap, published an updated version of the original in 2004, written by Rosalind Fergusson. In his review for The Guardian newspaper, the critic Ian Sansom had this to say:[2]