Ellon Castle and gardens, formerly known as the Fortalice of Ardgith, is set within the town of Ellon, Aberdeenshire. Owned by a community trust in the 21st century, only ruins survive of the 16th-century castle – a scheduled monument – that may incorporate sections from the 15th century together with 18th-century renovations.

Historians date the early ownership of the land to the 13th century, when it was the principal seat of the Comyns, the family of Mormaers with control of the Buchan area; they had a motte castle on a nearby site. During the 15th century a fortalice was constructed by the Kennedy family of Kermuck, before further reconstruction in the following century. Rebuilt again in the first half of the 18th century, when the formal gardens were established, it was further remodelled in the second half of the century.

The castle was neglected and allowed to fall into disrepair for most of the first half of the 19th century, after which the next owner used explosives to demolish the substantial structure. The ruins that remained form a focal point in a formal six-acre (2.4 ha) garden completed in 1745; an older Category A listed sundial dating from about 1700 forms the garden’s centrepiece. Adjacent land, known as Deer Park, is also owned by the community trust.

In the mid-19th century a new mansion was built, but that too was demolished in 1927. The smaller, private dwelling house, now known as new Ellon Castle, comprises the remodelled office block and stables of the earlier structure; it is privately owned and is not part of the community trust property.

History

The Comyns: Motte Castle

A timbered motte castle existed on a different site[a]The site was recorded on an 1874 town plan as being opposite the New Inn on Market Street.[1] in Ellon, which later became known as Moot Hill or Earl’s Hill, dating back to the 13th-century rule of the Comyns.[2] One of the principal seats of the Mormaers who controlled Buchan,[3] the motte was used by Alexander Comyn as the prime centre to carry out legal affairs.[4] Surrounded by a deep ditch, the level hill of earth was topped by a wooden tower containing accommodation for the family. A drawbridge prevented intruders gaining access to the timber staircase on the side of the slope leading to the palisade around the tower. Barns, stables and other ancillary structures were housed in another courtyard alongside it that incorporated the same protection measures.[1] After Robert the Bruce defeated Comyn’s son, John, at the Battle of Barra on 24 December 1307, there followed the Harrying of Buchan and Ellon was destroyed by fire;[1] the earthen mound survived until it was flattened at the start of the 19th century.[5] The downfall of the Comyns saw the ownership of the lands returned to the Crown which held them until gifted to Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan by Robert II of Scotland.[6]

The Kennedys: Fortalice

Land known as the Hill of Ardgith was sold by Isobel Moffat to Thomas Kennedy in 1413.[7] Kennedy – sometimes spelt as Kynidy – had been appointed as hereditary Constable of Aberdeen by the Duke of Albany in appreciation for his actions during the Battle of Harlaw.[8] A fortification was constructed at some point after the purchase date of the land and before 1500;[9] originally known as the Fortalice of Ardgith,[10] the castle was probably built by the Kennedy of Kermuck – sometimes recorded as Kinmuck – family and was used as their family seat.[11] According to the archaeology historian W. Douglas Simpson[12] the basement vault dates to the 15th century and pre-dates any later remains.[13] The castle was reconstructed in the late 16th century, work that, according to Simpson, was undertaken by the masons John and Thomas Leiper, who were also responsible for work at nearby Tolquhon Castle, the House of Schivas and Castle Fraser.[13][14]

A stone bearing the Kennedy arms is set into the ruins.[15] Dated 1635,[10] the marriage stone pictures a shield and bears the initials G. K.[15] The castle was ransacked by Royalists in 1644[16] then, a few years later in 1652, Kennedy became involved in a dispute with his neighbours, the Forbes of Waterton. The argument – centred around a ditch Kennedy wished to install – escalated; when the Sheriff of Banff attempted to intervene, a fight between Kennedy and his neighbours erupted. Forbes was killed and the Sheriff Clerk was severely injured. The lands became the property of the Moir family of Stoneywood as the Kennedys were outlawed.[17]

In 1668 Sir John Forbes of Waterton, who later married the sister of the Earl of Aberdeen, Jane Gordon, purchased the estate from the Moirs. Their sons disposed of the estate in the first decade of the 1700s;[17] it is unlikely that any of the family lived there during the period of its ownership.[18]

18th-century rebuilding: Castle

An affluent merchant and Baillie of Edinburgh, James GordonAffluent merchant, baillie of Edinburgh, and owner Fortalice of Ardgith, now Ellon Castle., acquired the estate in 1706.[10][17][b]Sources differ as to the year of acquisition; Reverend McLeod quotes 1708[17] whereas most modern day historians, for instance W. Douglas Simpson,[19] Ian Shepherd[16] and Historic Scotland,[10] give 1706. Born in 1665,[20] he was the son of a farmer and originated from Bourtrie;[17][19] in 1691 he married Elizabeth Glen in Canongate, Edinburgh.[18][21] The couple had three sons: John; Alexander;[22] and James.[18][c]Baillie Gordon’s youngest son, James, died in 1783; he “served with some distinction in the American War”.[18] On 28 April 1717, the two older boys, John and Alexander, were both around eight years old,[23][d]Pratt incorrectly gives the year of the killings as 1718[23] when they were murdered by their tutor, Robert Irvine.[24][e]The broadside published at the time describes Irvine as a chaplain.[22] The two boys were killed in Edinburgh after they reported seeing Irvine with their mother’s servant in a compromising situation.[25][f]Irvine was executed on 1 May 1717 for the crimes; before carrying out the hanging, the executioner cut off both Irvine’s hands.[22]

Baillie Gordon integrated the fortalice into a new sizeable structure that he rechristened from its former name of Fortalice of Ardgith to Ellon Castle, the first time the building became known by that name.[18] Gordon died “some years” after his sons were killed.[20] In 1752 the estate was sold to George Gordon, 3rd Earl of Aberdeen for £17,000. Writing in the mid-20th century, historian Cosmo Alexander Gordon attributes the sale to Gordon’s widow, Elizabeth, and his youngest son, adding that she also received 200 guineas to buy a gown in recompense for relinquishing her life rent entitlement.[18] Other historians, such as Christopher Dingwall, indicate the transaction was made by the baillie with his surviving son.[11]

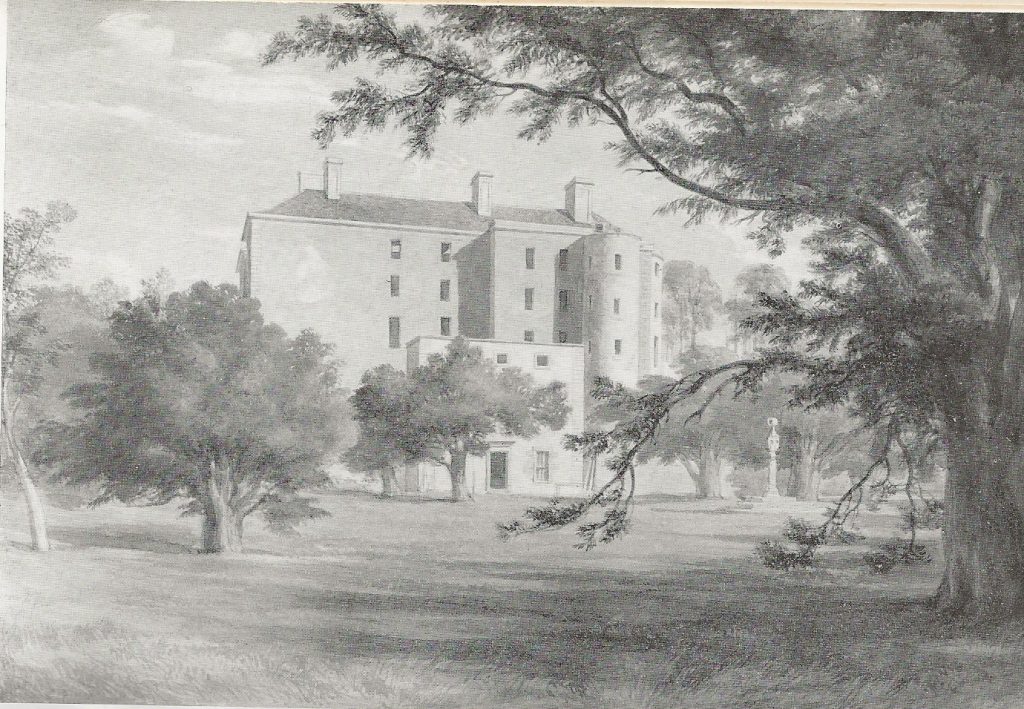

The earl, also known as “The Wicked Earl”,[16][g]The nickname alludes to his propensity of having mistresses.[26] embarked into an amorous relationship with Penelope Dering, a young English friend of one of his daughters, in 1782; that year, after installing his young mistress in the castle, he commissioned the architect John Baxter to extend the castle.[18][27] Over the next five years extensive work was carried out turning the castle into a harled and lime-washed four-storey construction with seven bays; part of the old tower houseCharacteristic style of Scottish castle building in the form of a tall tower, surrounded by one or more wings in L or Z-shaped floor plans in its later development. was integrated in the south-facing elevation.[11] The west-facing elevation featured a central door flanked with two moderately projecting wings; a pair of slightly protruding rounded bays were on the eastern side.[28] Rebuilding of the office suite from circa 1725, positioned just to the west of the castle, occurred at the same time.[11]

The poet Robert Burns was undertaking a tour of the Highlands with his companion, William Nicol, the “Son of Latin Prose”, at the end of the reconstruction work on the castle towards the end of 1787. The pair had dined in Ellon then attempted to visit the elderly sixty-five-year-old earl but were refused admission to the castle “owing to the jealousy of threescore over a kept country-wench.”[29]

Penelope and the earl had two children: a son, Alexander, born in 1783; and a younger daughter, also named Penelope.[18][30] Despite the earl having other mistresses ensconced in other properties he owned, including at Cairnbulg Castle, Ellon was his main residence; he died there on 13 August 1801.[18][26][h]Cosmo Alexander Gordon gives 1803 as the year of death[18] but 13 August 1801 is the correct date as indicated in contemporary newspapers.[31] His will named William, his only surviving legitimate son, as heir to the Ellon estate but with an entail stipulating reversion to Alexander, Penelope’s son, if William died childless.[18][i]The earl’s oldest legitimate son, George Gordon, Lord Haddo (1764–1791) predeceased him as he died at Gight following a riding accident on 2 October 1791.[32]

Decline and demolition

According to the New Statistical Account of 1841, when the earl died in 1801 and the Hon William Gordon inherited, the estate plus the castle were in excellent condition, reflecting the earl’s wealth and position in society.[11] William, however, had no interest in the castle or the estate. By 1808 he was intending to decimate the buildings, placing an advertisement in the Aberdeen Journal on 25 May to solicit interest in the building materials following demolition. After a successful legal challenge by his illegitimate half-brother, Alexander, William neglected the property; despite being the Member of Parliament representing Aberdeenshire he never lived in the area. By the time of his death in 1845, the buildings were dilapidated and roofless.[18][33][j]On 24 January 1811, the Court of Session upheld Alexander’s challenge, preventing the demolition due to the reversion included in the 3rd Earl of Aberdeen’s will.[33]

William died childless so the reversion stipulated in the 3rd Earl of Aberdeen’s will came into force giving the succession of the estate to Alexander. A soldier commissioned to the 15th Light Dragoons, he served in the Peninsular War and took part in the Corunna campaign before selling his commission in 1811. Together with his wife, Albinia Elizabeth Cumberland, who he married when he left the Dragoons, when he inherited the estate he had six children, four boys and two girls.[34][k]According to the ODNB entry for their youngest daughter, Eleanor Vere Crombie Boyle [née Gordon], the couple had nine children.[35]

19th-century: new mansion

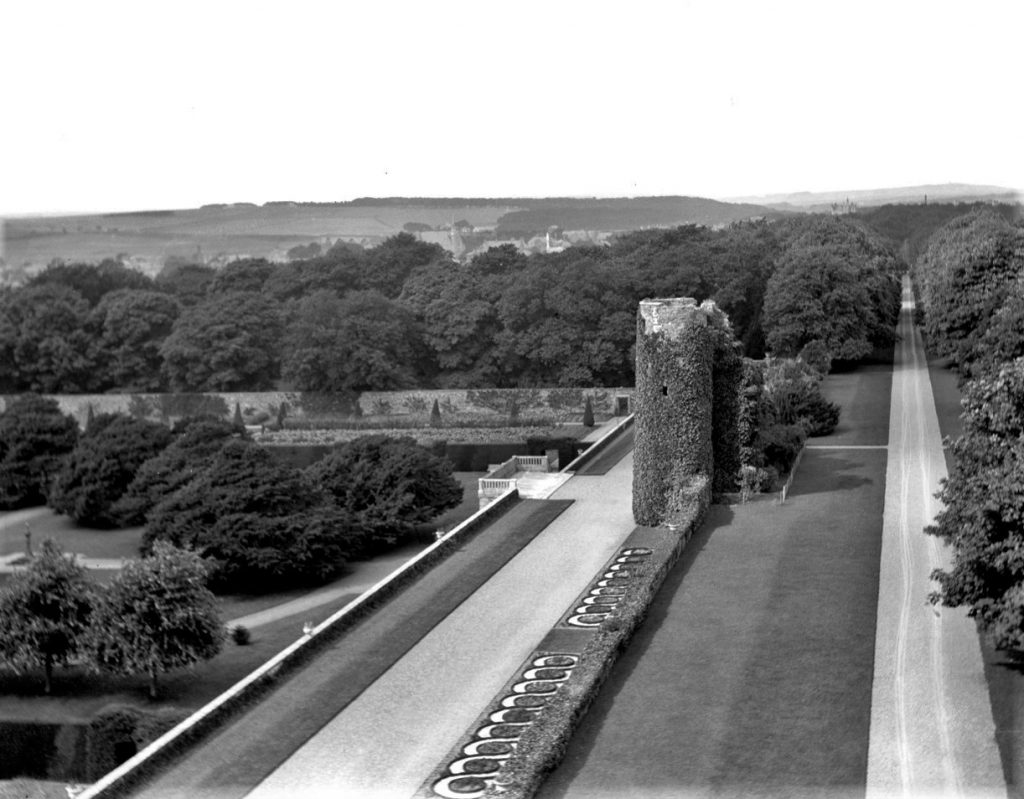

The castle was so ruinous when Alexander inherited, it was beyond repair; he commissioned the architect James Matthews of Mackenzie and Matthews to design a new mansion.[36][l]Cosmo Alexander Gordon attributes the design of the new mansion to “the firm of Smith in Aberdeen”[37] but records do not support this.[38] Explosives had to be deployed to demolish the substantial walls of the old structure.[37] The new mansion was completed in 1851; positioned beside the office suite that had been remodelled in 1782 by the 3rd earl, it was to the east of the previous site. The south wall of the old structure and the angle tower were deliberately retained to form a “picturesque” setting when approaching the new mansion from the west.[11]

Described by architectural historian Ian Shepherd as having “a grand Fyvie-like recessed arched centre flanked by tall bay windows and angle turrets, all crisply done in white granite”,[39][m]“Fyvie-like” is a reference to Fyvie Castle; the southern elevation of the new Ellon mansion included some design features used at Fyvie.[37] was, according to Cosmo Alexander Gordon, “intolerably inconvenient”.[37] Alexander had received £25,000 as part of his father’s will but by the time he finally inherited the Ellon estate, he was in debt due to his expensive life style. The building costs, improvements and upkeep of the estate were large and, when coupled with the agricultural depression together with Alexander’s unwise spending habits, led to another period of abandonment following his death in 1873.[40] Alexander’s eldest son, George John Robert Gordon, a diplomat who served as Minister Plenipotentiary, inherited but in 1885 passed the ownership to his son, Arthur John Lewis GordonDiplomat, artist and collector; owner of Ellon Castle from 1880s..[41] No one lived in the mansion from 1873 until 1885 when Arthur took up residence in the by then heavily debt-ridden estate. Despite the economies made, he failed to clear the debts; in 1913 the estate was put into administration under the control of trustees.[40] The administration supervised the letting of the property then, following Arthur’s death in 1918, secured the sale of the estate for a sum which covered the outstanding liabilities but with little profit.[11][42]

Dispersal and demolition

Sir Frederick BeckerIndustrialist with worldwide interests in the manufacture of pulp and paper, owner of Ellon Castle estate from 1919–1929. purchased the estate from the trustees in 1919.[41] A businessman with interests in the paper and pulp industry, he registered the estate as the Ellon Castle Company, beginning the fragmentation of the policies by selling all the farms. Under his ownership the old suite of offices were again remodelled for use as his residence and shooting lodge; he had the 1851 mansion commissioned by Alexander Gordon demolished in 1927.[41] Sir Frederick sold what remained of the estate to Sir Edward Reid in October 1929.[43]

Gardens

The overall gardens comprise three components: an upper area of woodland; the upper terrace; and the walled garden.[44]

The estate policies, including the formal garden and ruins, were acquired by the building and development companies, Scotia Homes and Barratt Homes. They applied for planning permission to develop the sections of the land – known as Castle Meadows and Castlewell – in 2009; the application was approved in 2012[45] but conditional in that the building companies were required to allocate the income from eleven of the proposed 247 properties to a community trust to maintain the gardens.[46][47] Later, in 2017, Deer Park was sold to the Trust for a nominal sum, £1, by Aberdeenshire Council.[48] Extending to around ten-acre (4.0 ha), it is edged by a twelve-foot (3.7 m) high rubble wall, four hundred-yard (365.8 m) in length, with central gate-piers.[11][49] The wall or deer dykes were built during Alexander Gordon’s ownership of the estate.[49]

Walled garden

The formal walled garden was established while the estate was owned by Baillie Gordon at the beginning of the eighteenth century.[21] No records survive indicating further development – or even maintenance – of the garden by the 3rd Earl although, considering his renovations to the castle buildings, it is unlikely he did not have some input.[11] Baillie Gordon’s original walled garden may have been extended by thirty-yard (27.4 m) to the south in around 1850.[50]

The centrepiece of the six-acre (2.4 ha) formal garden is a facet head sundial.[51] Dating from c. 1700, it is mounted on three steps and features twenty-four faces.[52] After being targeted by vandals and subjected to other damage over many years,[53] the Grade A listed sundial was restored in 2020.[54] Another smaller sundial, originally sited on the terrace, is described by Eleanor Vere Boyle in her book Seven Gardens and a Palace (1900).[11][n]Eleanor Vere Boyle, author and illustrator, was the youngest daughter of Alexander Gordon;[35] she did not reside in Ellon for any lengthy period but was strongly attached to it.[55] She writes: “On the smooth turf beneath the windows stands an ancient sundial. It is coarsely hewn rather than carved, in coarse granite, and represents four children’s heads turned in opposite directions, the three gnomens standing out from the base.”[56] The terrace sundial may have been erected as a memorial to Baillie Gordon’s two murdered children,[24] although Boyle does not mention this.[57]

Old castle ruins and garden house

Forming a “romantic” focal point in the formal walled garden,[58] the old castle ruins are set above and behind a garden house that was constructed either by Baillie Gordon or the 3rd Earl of Aberdeen but most likely the former. Originally a three-storey, flat-roofed harled building, the top floor was removed and a parapet added instead when the new mansion was built in 1851.[59]

Notes

| a | The site was recorded on an 1874 town plan as being opposite the New Inn on Market Street.[1] |

|---|---|

| b | Sources differ as to the year of acquisition; Reverend McLeod quotes 1708[17] whereas most modern day historians, for instance W. Douglas Simpson,[19] Ian Shepherd[16] and Historic Scotland,[10] give 1706. |

| c | Baillie Gordon’s youngest son, James, died in 1783; he “served with some distinction in the American War”.[18] |

| d | Pratt incorrectly gives the year of the killings as 1718[23] |

| e | The broadside published at the time describes Irvine as a chaplain.[22] |

| f | Irvine was executed on 1 May 1717 for the crimes; before carrying out the hanging, the executioner cut off both Irvine’s hands.[22] |

| g | The nickname alludes to his propensity of having mistresses.[26] |

| h | Cosmo Alexander Gordon gives 1803 as the year of death[18] but 13 August 1801 is the correct date as indicated in contemporary newspapers.[31] |

| i | The earl’s oldest legitimate son, George Gordon, Lord Haddo (1764–1791) predeceased him as he died at Gight following a riding accident on 2 October 1791.[32] |

| j | On 24 January 1811, the Court of Session upheld Alexander’s challenge, preventing the demolition due to the reversion included in the 3rd Earl of Aberdeen’s will.[33] |

| k | According to the ODNB entry for their youngest daughter, Eleanor Vere Crombie Boyle [née Gordon], the couple had nine children.[35] |

| l | Cosmo Alexander Gordon attributes the design of the new mansion to “the firm of Smith in Aberdeen”[37] but records do not support this.[38] |

| m | “Fyvie-like” is a reference to Fyvie Castle; the southern elevation of the new Ellon mansion included some design features used at Fyvie.[37] |

| n | Eleanor Vere Boyle, author and illustrator, was the youngest daughter of Alexander Gordon;[35] she did not reside in Ellon for any lengthy period but was strongly attached to it.[55] |