The Great Haigh Sough[a] A sough is a tunnel or adit. was driven under Sir Roger Bradshaigh’s Haigh HallHistoric country house in Haigh, near Wigan in Greater Manchester England. estate to drain his coal and cannelType of bituminous coal. pits in Haigh on the Lancashire CoalfieldThe Lancashire and Cheshire Coalfield in North West England was one of the most important British coalfields. Its coal seams were formed from the vegetation of tropical swampy forests in the Carboniferous period more than 300 million years ago.. Work started in 1653 and finished in 1670. The sough’s portal and two metres (6.6 ft) of tunnel, from where it discharges water into the Yellow Brook at Bottling Wood, is a scheduled monument.

The tunnel, 1120 yards (1,024 m) long, up to 6 feet (2 m) wide and 4 feet (1.2 m) high, was up to 49 yards (45 m) deep. It was driven without the use of explosive by men using picks, hammers, wedges and spades. The miners would have encountered blackdampDamps is a collective name given to all gases other than air found in coal mines in Great Britain. The chief pollutants are carbon dioxide and methane, known as blackdamp and firedamp respectively. . Progress was slow, about 4 feet (1.2 m) per week or 66 yards (60 m) per year. The sough passed through hard sandstones, mudstones and the Cannel and King Coal seams.

History

Cannel coalType of bituminous coal. had been dug from bell pits on Bradshaigh’s estate where the seam was very close to the surface near the Old School Cottages since the 14th century.[1] The sough was driven to drain the pits, which produced coal and cannel, and extended the life of their shallow workings, which were prone to flooding. The sough, a major investment, was considered preferable to winding water from the workings by the primitive methods available at the time.[2] Bradshaigh recorded a detailed survey of the sough and its shafts with instructions for maintenance so that, “the benefit of my 16 years labour, charge and patience (which it pleased God to crown with success for me and my posterity) may not be lost by neglect.”[3]

Such was the importance of the sough that in 1687, the estate bailiff, Thomas Winstanley, ordered its inspection and cleaning from bottom to top at least every two months and “the least decay thereof in any place speedily and substantially repaired”.[4] Cleaning involved clearing small rock falls and removing the build-up of deposited ochre (Hydrated iron oxide). It was inspected 14 times between 1759 and 1767 and in 1768 workmen spent 49 weeks cleaning the sough and a payment was made for repairing the hoppets (buckets) used to haul debris up the nearest shaft.[5] Regular inspections were carried out until 1923 and its abandonment ultimately led to the flooding of the Aspull and Westhoughton pits in 1932.[6]

Supporting pillars of cannel were accidentally ignited in the Cannel seam in March 1737 and the underground fire was still burning in the October despite the ventilation shafts being covered. The fire was eventually extinguished in 1738 after the sough was dammed and the workings flooded.[7]

Sough

The 1120 yard-long tunnel, up to six feet wide and four feet high, had ten ventilation shafts each up to 3 yards wide and up to 49 yards deep. Driven from Bottling Wood to Park Pit, work started in 1653 and finished in 1670.[6] The miners used picks, hammers, wedges and spades and would have encountered blackdamp which would have extinguished their candles warning them of its presence.[8] The sough was completed without using explosives but it is possible that fires were lit against the rock at the end of a shift to help break it.[9] The shafts were used to remove rock as the miners cut the tunnel. Progress averaged 66 yards per year or about 4 feet a week.[10] Between its outlet and Park Pit the sough passed through several layers of hard sandstones, mudstones and the Cannel and King Coal seams. Seven ventilation shafts, roughly aligned with the main drive to Haigh Hall, were worked as small collieries and the rest filled in. The first shaft from the outfall, Cannel Hollows Pit, was 23 feet (7 m) deep. The fifth shaft, Sandy Beds Pit, was sunk 23 yards (21 m) to the sough and met the coal seam at 14 yards (13 m) . Its shaft was rectangular in section but all the others were round. The last shaft before Park Pit was 48 yards (44 m) deep to the sough and met the Cannel seam at 32 yards (29 m). The shaft at Park Pit was 48 yards (44 m) to the sough and met the King Coal seam at 41 yards (37 m).[11]

In the 18th century the sough was extended and other levels were driven to connect new pits as they became operational. Some pits had their own soughs.[5] The sough was extended to Fothershaw Pit in about 1856 and, by the Wigan Coal and Iron Company, to Aspull Pumping Pit after 1866[12] extending its length to 4600 yards (4,206 m).[9]

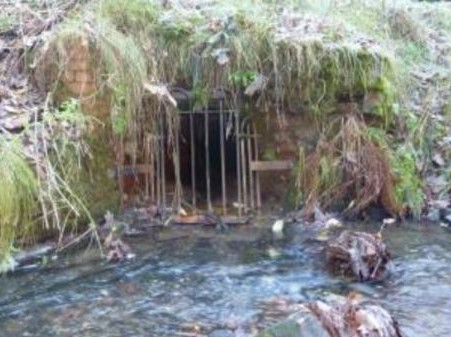

The sough’s entrance portal is constructed from brick and stone and leads into a brick lined culvert. The portal and two metres of the culvert is a scheduled monument.[13]

Discharge

The sough discharged iron-rich minewater into the Yellow Brook in Bottling Wood, discolouring it and the River Douglas downstream with ochre deposits. Water infiltrated the pits, not via the shafts, but by percolating through the overlying porous rock strata containing bands of ironstone.[14] After heavy rain in December 1929, 561,600 gallons of water drained from the sough into the brook at a rate of 290 gallons per minute. In 1978 the rate was 352 gallons per minute, more than 500,000 gallons per day.[15]

In 2004 the Coal Authority provided a passive treatment plant in a scheme costing £750.000. Work was undertaken by Ascot Environmental who built a pumping station, pipelines, settlement lagoons, reedbeds and landscaped the site. The scheme has improved the water quality, removed the manganese and iron which was causing the discolouration and allowed fish to repopulate the brook.[16]