Wikimedia Commons

Jack Sheppard (4 March 1702 – 16 November 1724) was a notorious thief in early 18th-century London. Born into a poor family, he was apprenticed as a carpenter, but took to theft and burglary with little more than a year of his apprenticeship left to complete. He was arrested and imprisoned five times in 1724, but escaped four times, making him a notorious public figure and wildly popular with the poorer classes. Ultimately he was hanged at Tyburn in front of the largest crowd ever then seen in London, ending his brief criminal career after less than two years.

Sheppard was as renowned for his attempts to escape from prison as he was for his crimes. An autobiographical Narrative, thought to have been ghostwritten by Daniel Defoe, was on sale the day following his execution,[a]Compiled for Applebee’s Original Weekly Journal, probably by Daniel Defoe, and endorsed by Sheppard at his hanging in November 1724. quickly followed by popular plays. The character of Macheath in John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728) was based on Sheppard, keeping him in the limelight for for more than a hundred years. He returned to the public consciousness in 1839, when William Harrison Ainsworth’s novel Jack Sheppard was published. The popularity of his tale, and the fear that others would be drawn to emulate his behaviour, led the authorities to refuse to license any plays in London with “Jack Sheppard” in the title for almost forty years.

Early life

Sheppard was born in White Row, in London’s Spitalfields, the son of Thomas Sheppard, a carpenter, and his wife Mary.[1] He was baptised on 5 March, the day after he was born, at St Dunstan’s, Stepney, suggesting a fear of infant mortality by his parents, perhaps because the newborn was weak or sickly. His parents named him after an older brother, John, who had died before his birth. In life, he was better known as Jack, or even “Gentleman Jack” or “Jack the Lad”. He had a second brother, Thomas, and a younger sister, Mary. Their father died while Sheppard was young, and his sister died two years later.[2]

Sheppard received a rudimentary education at Mr Garrett’s School near St Helen’s, Bishopsgate. In or soon after 1714 he was employed as a servant by William Kneebone, a woollen draper, who, on 2 April 1717, apprenticed him to Owen Wood, a carpenter in Drury Lane. Sheppard was reckoned to be a “talented apprentice”, but he fell into the company of Joseph Hayne, a button-moulder who owned a shop nearby, and ran the Black Lion tavern off Drury Lane.[1]

According to Sheppard’s autobiography, he had been an innocent until going to Hayne’s tavern, but there began an attachment to strong drink and the affections of Elizabeth Lyon, a prostitute also known as Edgworth Bess. In his History, Defoe records that Bess was “a main lodestone in attracting of him [Sheppard] up to this Eminence of Guilt.”[3] The historian Peter Linebaugh offers a more romantic view, that Sheppard’s transformation was a liberation from the dull drudgery of indentured labour, and that he progressed from pious servitude to self-confident rebellion.[4]

Criminal career

Sheppard’s first recorded theft took place in early 1723, when he stole two silver spoons while on an errand for his master to the Rummer Tavern in Charing Cross[1] and he began stealing goods from the houses where he was working.[5] He quit the employ of his master in August 1723 with little more than a year of his apprenticeship left, and drifted into a life of professional crime.[1]

Arrested and escaped twice

Wikimedia Commons

By February 1723 Sheppard was carrying out burglaries with his brother and Elizabeth Lyon, but their partnership was short-lived. Thomas was apprehended at the beginning of April and informed against his accomplices; shortly afterwards a warrant was issued for Jack’s arrest. He was apprehended and held for the night in the parish roundhouse of St Giles-in-the-Fields, but within two hours had escaped by breaking a hole through the roof: the first of his daring and skillful escapes.[1]

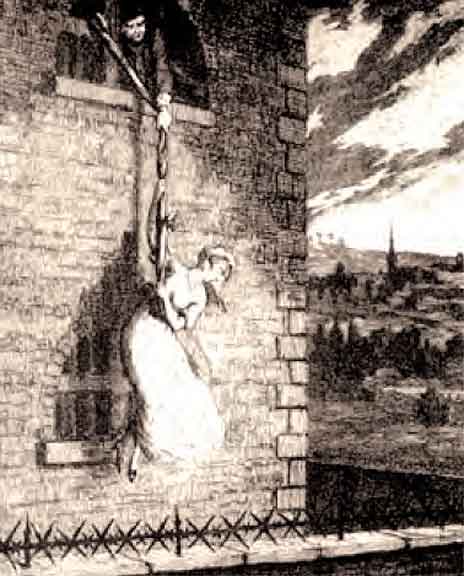

On 19 May 1724 Sheppard was arrested for a second time, caught in the act of picking a pocket in Leicester Fields (near present-day Leicester Square). He was detained overnight in St Ann’s Roundhouse in Soho and visited there the next day by Lyon; she was recognised as his pertner and also apprehended. The couple appeared before Justice Walters, who sent them to the New Prison in Clerkenwell, but they escaped from their cell within a matter of days. By 25 May, Sheppard and Lyon had filed through their manacles; they removed a bar from the window and used their knotted bed-clothes to descend to ground level. Finding themselves in the yard of the neighbouring Bridewell, they clambered over the 22-foot-high (6.7 m) prison gate to freedom. This feat was widely publicised, not least because Sheppard was a small man, and Lyon was a large, buxom woman.[6][b]Defoe’s History reports that Lyon was “more corpulent than himself [Sheppard]”. One of the notices for Sheppard’s arrest describes him as “about five foot four inches high, very slender”.[1]

Third arrest, trial and third escape

In 1724 Sheppard joined forces with the footpad Joseph “Blueskin” Blake, and the pair experimented with highway robbery on the Hampstead Road. He still continued with his burglaries, including one at the house of his former master, Willian Kneebone. By now Sheppard’s activities had come to the attention of the well-known receiver and thief-taker, Jonathan Wild, whom he antagonised by being unwilling to allow Wild to fence his stolen booty.[1] Wild was not prepared to permit Sheppard to continue outside his control, and began to seek his arrest.[7] Unfortunately for Sheppard, his own fence, William Field, was one of Wild’s men. Wild believed Lyon would know of Sheppard’s whereabouts, so he plied her with drink at a brandy shop near Temple Bar until she betrayed him. Sheppard was arrested a third time at Blueskin’s mother’s brandy shop in Rosemary Lane, east of the Tower of London (later renamed Royal Mint Street), on 23 July by Wild’s henchman, Quilt Arnold.[8]

Sheppard was imprisoned in Newgate Prison pending his trial at the next Assize of oyer and terminer. Largely on the strength of Wild’s evidence, in August Sheppard was convicted of the Kneebone burglary and sentenced to death. On 31 August, four days before the date set for his execution, Sheppard escaped.[1] Having loosened an iron bar in a window used when talking to visitors, he was visited by Lyon and Poll Maggott, who distracted the guards while he removed the bar. His slight build enabled him to climb through the resulting gap in the grille, and he was smuggled out of Newgate in women’s clothing that his visitors had brought him.[9] He took a coach to Blackfriars Stairs, a boat up the River Thames to the horse ferry in Westminster, near the warehouse where he hid his stolen goods, and made good his escape.[3]

Fourth arrest and final escape

Sheppard fled from London and spent a few days at Wavenden, Buckinghamshire, but was soon back in town.[10] He was recaptured on Finchley Common on 10 September by a posse from Newgate, and returned to the condemned cell at Newgate. His fame had increased with each escape, and he was visited in prison by the great, the good and the curious. His plans to escape were thwarted when the guards found files and other tools in his cell, and he was transferred to a strong-room in Newgate known as the Castle, clapped in leg irons, and chained to a metal staple in the floor by a horse padlock.[1]

Wikimedia Commons

Despite the precautions, Sheppard made his fourth and most daring escape on 15 October. He unlocked his handcuffs and removed the chains. Still encumbered by his leg irons, he attempted to climb up the chimney, but his path was blocked by an iron bar set into the brickwork. He removed the bar and used it to break through the ceiling into the Red Room above the Castle, which had last been in use seven years earlier to confine aristocratic Jacobite prisoners after the Battle of Preston. Still wearing his leg irons, as night fell Sheppard then broke through six barred doors into the prison chapel, then on to the roof of Newgate, 60 feet (18 m) above the ground. He went back down to his cell to get a blanket, then back to the roof of the prison, and used the blanket to reach the roof of an adjacent house, owned by William Bird, a turner. He broke into Bird’s house, and went down the stairs and out into the street at around midnight without disturbing the occupants. Escaping through the streets to the north and west, Sheppard hid in a cowshed in Tottenham (near modern Tottenham Court Road). Spotted by the barn’s owner, Sheppard told him that he had escaped from Bridewell Prison, having been imprisoned there for failing to support a (nonexistent) bastard son. His leg irons remained in place for several days until he persuaded a passing shoemaker to accept the considerable sum of 20 shillings to bring a blacksmith’s tools and help him remove them, telling him the same tale.[11] Daniel Defoe, in his account of the escape in The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard, reports the belief in Newgate that the Devil came in person to assist Sheppard’s escape.[3]

Final capture

Sheppard’s final period of liberty lasted just two weeks. He broke into the Rawlins brothers’ pawnbroker’s shop in Drury Lane on the night of 29 October 1724, taking a black silk suit, a silver sword, rings, watches, a wig, and other items.[12] Finely dressed in the stolen attire, he was arrested in a Drury Lane brandy shop two days later, very drunk.[1]

Back in Newgate, Sheppard was this time held in the Middle Stone Room, where he could be kept under constant observation. He was by now so celebrated that crowds flocked to see him, for which his jailers made a charge; they were said to have earned more than £200. One of Sheppard’s visitors was Sir James Thornhill, serjeant-painter to the crown, who sketched several portraits of him.[1]

Sheppard came before Mr Justice Powis in the Court of King’s Bench at Westminster Hall on 10 November. He was offered the chance to have his sentence reduced by informing on his associates but refused, and the death sentence was confirmed.[13]

Execution

The following Monday, 16 November, Sheppard was taken to the gallows at Tyburn to be hanged. The procession halted at the City of Oxford tavern on Oxford Street, where Sheppard drank a pint of sack.[14][c]Sack is a type of fortified wine now more commonly known as sherry. Watched by an estimated 200,000 people,[15] “the largest crowd Londoners could then remember”,[1] Sheppard’s body was cut down after the prescribed fifteen minutes.[d]Until the mid-19th century, the short drop method of hanging was used, in which the victim is slowly strangled to death. The long drop method, which broke the victim’s neck thus causing instantaneous death, was not adopted in England until 1872.[16] The crowd pressed forward to prevent its removal, fearing it would be dissected, but in doing so prevented Sheppard’s friends from implementing a plan to take his body to a doctor in an attempt to revive him. Sheppard’s remains were buried in the churchyard of St Martin-in-the-Fields that evening.[17]

Legacy

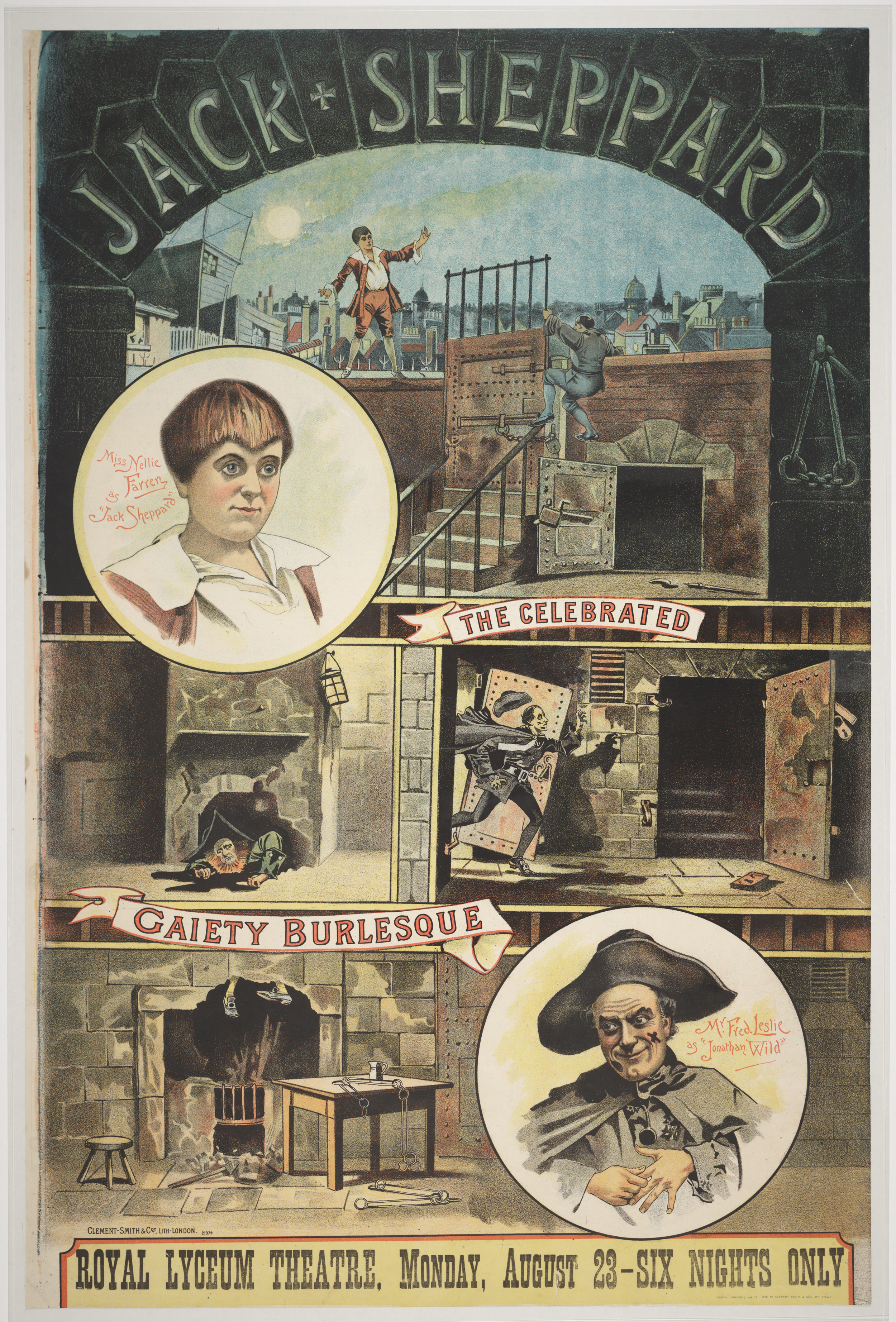

Wikimedia Commons

John Applebee published the supposedly autobiographical A Narrative of All the Robberies, Escapes, Etc. of Jack Sheppard the day following the execution,[18] and Sheppard’s story was adapted for the stage almost immediately. Harlequin Sheppard. A night scene in grotesque characters, a pantomime by John Thurmond, opened at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane on Saturday 28 November, only two weeks after Sheppard’s hanging.[17] In a contemporary sermon, a London street preacher drew on Sheppard’s popular escapes as a way of holding his congregation’s attention:

William Harrison Ainsworth

English historical novelist, at one time considered a rival to Charles Dickens.‘s best-selling romance, Jack Sheppard (1839), returned Sheppard to the public spotlight, and led to a spate of imitative novels and stage plays, arousing fears among the middle classes that stories glorifying criminals like Sheppard might tempt impressionable working-class boys into a life of crime, the so-called Newgate ControversyEarly form of sensation literature, drawing its inspiration from the Newgate Calendar, first published in 1773 and containing biographies of famous criminals..[1] The novelist William Makepeace Thackeray wrote in a letter to his mother, dated December 1839, that at one theatrical adaptation of Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard he had seen people in the lobby selling “Shepherd-bags”, containing “a few picklocks … a screwdriver and iron lever”, adding that “one or two young gentlemen have already confessed how much they were indebted to Jack Sheppard who gave them ideas of pocket-picking and thieving [which] they never would have had but for the play”.[20] Successive lord chamberlains were so concerned about the effect on public morality that for almost forty years from 1840 they refused to license the performance of plays titled “Jack Sheppard”.[1]

Sheppard’s fame declined during the 20th century, but there were nevertheless three film adaptations of his life, including the “lavish but commercially unsuccessful” Where’s Jack? (1969), starring Tommy Steele in the title role.[1]

— Philip Sugden

Notes

| a | Compiled for Applebee’s Original Weekly Journal, probably by Daniel Defoe, and endorsed by Sheppard at his hanging in November 1724. |

|---|---|

| b | Defoe’s History reports that Lyon was “more corpulent than himself [Sheppard]”. One of the notices for Sheppard’s arrest describes him as “about five foot four inches high, very slender”.[1] |

| c | Sack is a type of fortified wine now more commonly known as sherry. |

| d | Until the mid-19th century, the short drop method of hanging was used, in which the victim is slowly strangled to death. The long drop method, which broke the victim’s neck thus causing instantaneous death, was not adopted in England until 1872.[16] |

References

Bibliography

This article may contain text from Wikipedia, released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.