The Manchester Royal Exchange is a Grade II listed building in Manchester, England. It is located in the city centre on the land bounded by St Ann’s Square, Exchange Street, Market Street, Cross Street and Old Bank Street. The complex includes the Royal Exchange Theatre and the Royal Exchange Shopping Centre.

The Royal Exchange was heavily damaged in the Manchester BlitzHeavy bombing of the city of Manchester and its surrounding areas in North West England during the Second World War by the Nazi German Luftwaffe. and in the 1996 Manchester bombingAttack carried out by the Provisional Irish Republican Army on Saturday 15 June 1996, when they detonated a 15,000 kg bomb in the centre of Manchester, England.. The current building is the most recent of several on the site that were used for commodities exchange, primarily but not exclusively for cotton and textiles.

History

The cotton industry in Lancashire was served by cotton importers and brokers based in Liverpool, who supplied Manchester and surrounding towns with raw cotton to spin into yarn and produce finished textiles. The Liverpool Cotton Exchange traded in imported raw cotton. In the 18th century the trade was part of part the slave trade, in which African slaves were transported to America where the cotton was grown and then exported to Liverpool where the raw cotton was sold.[1] Raw cotton was processed in Manchester and the surrounding cotton towns, and Manchester Royal Exchange traded in spun yarn and finished goods which were sold across the world. Manchester’s first exchange opened in 1729 but had closed by the end of the century. As the cotton industry boomed, the need for a new exchange was recognised.

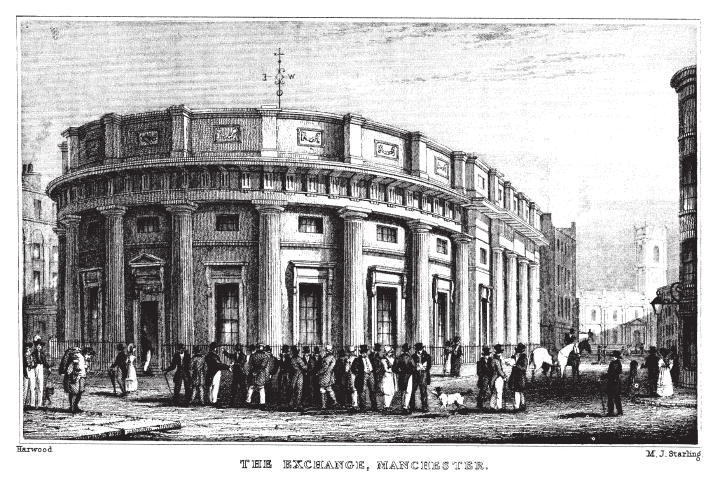

Thomas Harrison designed the second exchange that was completed in 1809 at the junction of Market Street and Exchange Street.[1] Harrison’s exchange, of two storeys above a basement constructed in Runcorn stone, was designed in the Classical style. The cost of £20,000, was paid for in advance by 400 members, who bought £50 shares and paid £30 each to buy the site. Its semi-circular north façade had fluted Doric columns. The exchange room where business was conducted covered 812 square yards (679 m2). The ground floor contained the members’ library with more than 15,000 books. The basement housed a newsroom lit by a dome and plate glass windows, its ceiling was supported by a circle of Ionic pillars spaced fifteen feet (5 m) from the walls. The first-floor dining-room was accessed by a geometrical staircase. The exchange opened to celebrate of the birthday of George III in 1809. It also contained other anterooms and offices.[2]

As the cotton trade continued to expand, larger premises were required and an extension was completed in 1849. Queen Victoria granted the exchange the title Manchester Royal Exchange after a visit in 1851.[3] The exchange was run by a committee of Manchester industrialists. From 1855 until 1860 the committee was chaired by Edmund Buckley.[4]

The exchange was replaced by a third designed by Mills & Murgatroyd between 1867 and 1874.[5] It was extended and modified by Bradshaw Gass & Hope between 1914 and 1931 to form the largest trading hall in England.[5][6] The trading hall had three domes and was double the size of the current hall.[7] The colonnade parallel to Cross Street marked its centre. On trading days merchants and brokers struck deals which supported the jobs of tens of thousands of textile workers in Manchester and the surrounding towns.[1] Manchester’s cotton dealers and manufacturers trading from the Royal Exchange earned the city the name, CottonopolisThe nickname given to Manchester, the world's first industrial city, a metropolis centred on cotton trading..[8]

The exchange was seriously damaged during the Second World War, when it took a direct hit from a bomb during a German air raid in the Manchester Blitz at Christmas in 1940. Its interior was rebuilt with a smaller trading area.[5][8][9] The top stages of the clock tower, which had been destroyed, were replaced in a simpler form. Trading ceased in 1968, and the building was threatened with demolition.[5][10]

The exchange remained empty until 1973 when a theatre company moved in. The Royal Exchange Theatre was founded in 1976.[11]

The exchange was again damaged when an IRA bombAttack carried out by the Provisional Irish Republican Army on Saturday 15 June 1996, when they detonated a 15,000 kg bomb in the centre of Manchester, England. exploded in Corporation Street less than 50 yards (46 m) away on 15 June 1996. The blast caused the dome to move, although the main structure was undamaged.[12] That the adjacent St Ann’s Church survived almost unscathed is probably due to the sheltering effect of the stone-built exchange. Repairs took more than two years and cost £32 million, a sum provided by the National Lottery.[11] Whilst the exchange was rebuilt, the theatre company moved to in Castlefield. The theatre was repaired and provided with a second performance space, a bookshop, craft shop, restaurant, bars and rooms for corporate hospitality. The theatre’s workshops, costume department and rehearsal rooms were moved to Swan Street. The refurbished theatre re-opened on 30 November 1998 by Prince Edward. The opening production, Stanley Houghton’s Hindle Wakes was the play that should have opened the day the bomb was exploded.[12]

Architecture

The exchange has four storeys and two attic storeys built on a rectangular plan in Portland stone. It was designed in the Classical style. Its slate roof has three glazed domes and on the ground floor an arcade orientated east to west. It has a central atrium at first-floor level. The ground floor facade has channelled rusticated piers and the first, second and third floors have Corinthian columns with entablature and a modillioned cornice. The first attic storey has a balustraded parapet and the second attic storey has a mansard roof. At the north-west corner is a Baroque turret and there are domes over other corners. The west side has a massive round-headed entrance arch with wide steps up and the first and second floor windows have round-headed arches. The third floor and first attic storey have mullioned windows.[7]

Theatre

Inside the Great Hall, the theatre occupies a seven-sided steel and glass module. It is a pure theatre in the round in which the stage area is surrounded on all sides and above, by seating.[13] Its unique design is intended to create a vivid and immediate relationship between actors and audiences. As the floor of the exchange was unable to take the weight of the theatre and its audience, the module is suspended from the four columns carrying the hall’s central dome. Only the stage area and ground-level seating rest on the floor. The 150-ton theatre structure opened in 1976 at a cost of £1 million amid some scepticism from Mancunians.[14]

The theatre can seat an audience of up to 800 on three levels, making it the largest theatre in the round in the world. At ground level, 400 seats are in a raked configuration and above them are two galleries, each with 150 seats set in two rows. The 90-seat studio theatre with no fixed stage area and moveable seats, allows for a variety of production styles (in the round, thrust etc.) and is used by visiting touring theatre companies, stand-up comedians and performances for young people.[15]