Cottonopolis was the nickname given to Manchester, the world’s first industrial city, a metropolis centred on cotton trading that serviced the mills in its hinterland. Manchester was the international centre of the cotton and textile trade during the 19th century.

Manchester’s journey from a small town to a major industrial and trading centre was the result of sixty years of sustained, dynamic economic growth. The Industrial Revolution took hold early in Manchester. The cotton industry was established in the region by the 1790s, supported by its damp climate, soft water supply, proximity to the Port of Liverpool for imports of raw cotton and its position on the Lancashire CoalfieldThe Lancashire and Cheshire Coalfield in North West England was one of the most important British coalfields. Its coal seams were formed from the vegetation of tropical swampy forests in the Carboniferous period more than 300 million years ago.. Improvements to the early transport network, the Duke of Bridgewater’s canal in 1762 and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1830 were crucial in supporting Manchester’s growth.[1]

Innovations in textile engineering and mill architecture, the development of steam power, a rapidly growing population, the establishment of banks and the development of warehouses all contributed to the rise of Manchester as a trading and commercial centre with few rivals.

Transport

The region was at the heart of the transport revolution that started with the Bridgewater Canal’s completion, bringing cheap coal from the Duke of Bridgewater’s pitsExtensive network of underground canals that drained the Duke of Bridgewater's coal pits emerge into the open at the Delph in Worsley, Greater Manchester. to Manchester; the canal’s extention to Runcorn in 1776 halved the price of transporting raw cotton from the Port of Liverpool. In 1804 the Rochdale Canal – the first trans-Pennine canal – was completed to Manchester and linked to the Bridgewater at Castlefield in Manchester,[2] and the Ashton Canal joined it near London Road turning the town into an inland port. The quays and wharves were lined with warehouses and cotton mills.[3]

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway, promoted as a passenger line rather than the mineral lines built between Stockton and Darlington and Bolton and LeighLancashire's first public railway, promoted as a mineral line in connection with William Hulton's coal pits to the west of his estate at Over Hulton. , demonstrated the potential of rail transport and provided speedy transportation for raw cotton.[3]

Mills

In 1781 Richard Arkwright opened the world’s first steam-driven textile mill on Miller Street. It started the mechanisation of the textile industry and 86 steam-powered spinning factories had been built in Manchester and adjoining Salford by 1816.[4] Manchester became the world’s first centre of mass production and as industry moved from workers’ homes to factories, Manchester and its hinterland became the largest and most productive cotton spinning centre in the world using 32 per cent of global cotton production in 1871.[5]

Ancoats, part of a planned expansion of Manchester, became the first industrial suburb centred on steam power. Mills were built near the Rochdale Canal with architectural innovations such as fireproofing using iron and reinforced concrete.[6] Numbers of cotton mills declined in Manchester in the mid-19th century but more opened in the surrounding towns, Bury, Oldham, Rochdale, Bolton[a]known as “Spindleton” in 1892[7] and in Blackburn, Darwen, Rawtenstall, Todmorden and Burnley. As the manufacturing centre of Manchester shrank, its commercial centre, warehouses, banks and services for the cotton towns and villages within a 12-mile (19 km) radius of the Royal Exchange grew.[8]

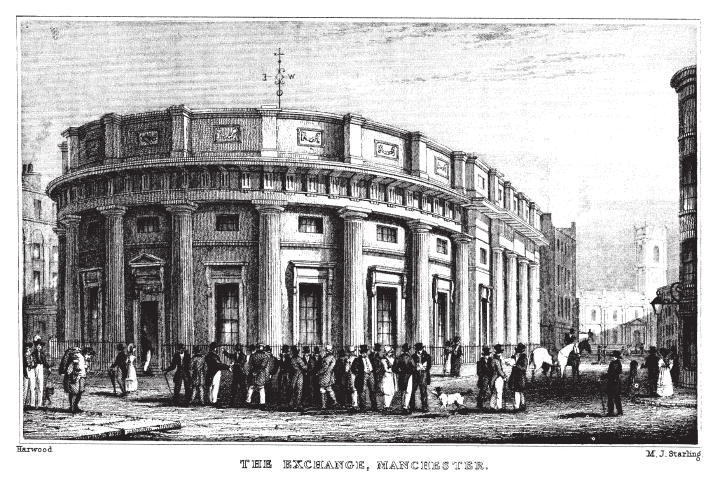

Exchanges

The cotton exchange trading hall became Manchester’s commercial centre. Sir Oswald Mosley, Lord of the Manor, built the first exchange for chapmen to transact business in the market place in 1727.[9] Thomas Harrison built a larger exchange in the Greek Revival style between 1806 and 1809.[10] When the exchange opened 400 shares were issued at £50 each and by 1815 it had 1600 subscribers[11] and Manchester was growing from a cotton manufacturing town to the trading centre of the cotton industry in Lancashire aided by the canal network.[12] Harrison’s exchange was enlarged in 1836 and 1845. Queen Victoria granted the exchange the title Manchester Royal ExchangeFormer cotton exchange damaged by two bombs, now comprising a theatre and shopping centre. after a visit in 1851.[13]

A third exchange, by Mills and Murgatroyd, opened in 1874.[14] It was built in the Classical style with Corinthian columns and a dome.[13] Between 1914 and 1921 architects Bradshaw Gass & Hope built the present exchange’s lavish Edwardian exterior.[14] Its vast hall, the world’s largest trading room, was 29.2 metres (95.8 ft) high and covered 3683 square metres (4,405 yd2). The membership of up to 11,000 cotton merchants met on Tuesdays and Fridays to trade their wares beneath the 38.5 metres (126.3 ft) high central glass dome. The exchange was badly damaged during the Second World War, and ceased operation for cotton trading in 1968.[14]

Warehouses

During the 18th century Manchester was already the centre for marketing textiles, and warehouses were a vital part of its economy.[4] Trade shaped the town, and by 1815 more than 1800 warehouses of every size and description had been built in Manchester’s commercial quarter, occupying a square mile of the modern city centre. The earliest were built around King Street and spread to Portland Street and Whitworth Street. They include warehouses along Charlotte Street, Princess Streets and the packing warehouses along Whitworth Street.[15] More money was invested in warehouses, 48 per cent of all property investment as compared to just 65 per cent in factories.[4] They were more than store rooms, they were showrooms where goods were displayed and sold to buyers from around the world.[16]

The warehouses, typically styled on the palazzi of Renaissance Italy, after 1839 gave the town a distinct appearance. Rows of warehouses, each four or five storeys high with high basements were entered by flights of stone steps into impressive foyers. They were constructed in brick with stone facings and prominent cornices.[17][18]

Banks

The growth of the cotton and aligned industries led to the establishment of banks. Byrom, Allen, Sedgwick and PlaceThe first bank in Manchester, founded in 1771. It collapsed in 1788 when one of its major borrowers declared bankruptcy., founded on 2 December 1771 in Bank Street, was the first bank to be established in Manchester.[20] Arthur Heywood’s Bank opened in 1772, but money was transferred daily to major banks in London.[21] The first bank to hold its own reserves of notes and coins was the Bank of Manchester, which opened on Market Street in 1829. The Manchester & Liverpool District Bank in Spring Gardens also opened in 1829,[22] followed by many others around Spring Gardens, Fountain Street and King Street, which became the central business district and banking centre.

Legacy

Examples of 18th and 19th-century cotton mills survive near the Rochdale Canal in Ancoats. Many Bridgewater Canal warehouses at Castlefield Basin are still standing and have been converted for modern use and the Huddersfield Narrow and the Rochdale Canals have been restored and major regeneration has taken place at New Islington and Piccadilly Village.

The Royal Exchange has survived two bombs and has been adapted as a theatre. The square mile of “warehouse city” is considered to be the finest example of a Victorian commercial centre in the United Kingdom.[15] Parts of the city centre are still dominated by the commercial buildings, banks and warehouses that were built on an unprecedented scale, giving Manchester a unique streetscape unlike any other city in Britain.[23] The survival of Manchester’s industrial and commercial heritage was a core component in the listing of Manchester and Salford on a tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[24]