The Worsley Navigable Levels is an extensive network of underground canals that emerge at the Delph in Worsley, Greater Manchester. The underground canals drained the Duke of Bridgewater’s coal workings, and special mine boatsBoats built to transport coal from the Duke of Bridgewater's pits in Worsley, nicknamed starvationers, transported coal from the coal pits to the start of the Bridgewater Canal at the Delph.

Started in 1759, the underground network eventually extended for more than fifty miles (80 km) on three levels, and incorporated a massive subterranean inclined plane. It serviced most of the Bridgewater pits and carried coal until 1887, when it continued to drain the coal measures and supply water for the Bridgewater Canal.

Background

Small-scale coal mining had been carried on in Worsley and the surrounding area from the Middle Ages where coal seams outcropped. Dame Dorothy LeghBorn Dorothy Egerton (1565–1639), also known as Dorothy Brereton, Lady of the Manor of Worsley, was a coal owner and benefactor of Ellenbrook Chapel near her home in Worsley, Lancashire. , Lady of the Manor of Worsley from 1598 owned small coal pits that were described as being equipped with “windlass, ropes and chains”.[1] In her will she left ten shillings each the workmen in her coal and cannelType of bituminous coal. pits in Middle Hulton. Also by her will, the manor passed to the son of her illegitimate half brother, Sir Thomas Egerton, Viscount Brackley, who had died in 1617. His son John Egerton, the Earl of Bridgewater succeeded to Worsley when Dorothy Legh died in 1639.

Scroop Egerton, 1st Duke of Bridgewater, inherited the Worsley estate in 1730. His fourth son John inherited the estate in 1745, but after his death in 1748 the estate passed to his fifth son Francis, who gained full control in 1757 when he became 21.[2] Francis Egerton, the 3rd Duke, was keen to exploit the coal under his largely agricultural estate, but the coal pits he inherited were small and particularly wet from water that percolated through porous sandstone above the coal.[3]

Massey’s Sough

Several coal seams outcropped on the Bridgewater land and coal was worked at the outcrop where it was easily accessible. The Four Foot mine[a] In Lancashire a coal seam is referred to as a mine, and the coal mine as a colliery or pit. outcrops north of Worsley Old Hall and around Parr Fold in Walkden. Scroop Egerton and his agent, John Massey, embarked on improving productivity, but water was a constant problem. The extent of the coal reserves was unproven and methods of finding it were primitive.[4]

Massey started a sough [b]A sough is a tunnel or adit. The Great Haigh SoughTunnel or adit driven under Sir Roger Bradshaigh’s Haigh Hall estate between 1653 and 1670, to drain his coal and cannel pits. at Haigh Near Wigan had been constructed between 1653 and finished in 1670. to drain as many pits as possible around Parr Fold where three coal seams outcropped within 300 yards (274 m) of each other. The sough was only large enough for the workers to enter and roughly constructed. It was about 1,100 yards long, 600 yards in tunnel and the rest in culvert. Over its length it descended at about 1 in 400 to empty into the Kempnough Brook. Pits up to 40 feet (12 m) deep at Parr Fold were drained of water. As deeper reserves were worked, water still had to be wound to the surface in tubs. The sough needed frequent maintenance, which was a filthy and dangerous job.[4]

Bridgewater Canal

Profits from the Duke’s collieries started to decline around 1757 as the seams dipped deeper into the ground and became much wetter. The 3rd Duke hired John Gilbert as agent for his estates in 1757. Gilbert moved into the Old Hall where he and the Duke discussed the improvements that were needed to make his coal pits more productive and able to meet the demand for coal in growing Manchester. They improved the sough and planned to extend it beyond Walkden and replaced the windlasses with horse gins. Steam pumps were introduced to remove water from pits along the Foor Foot mine near the Old Hall and test boreholes were made with augers and the new percussive drills to determine the extent of the coal reserves.[5]

The Duke was already planning to construct the Bridgewater Canal from Worsley village to Salford on the River Irwell but coal would still need to be moved from the pits either by packhorse or tramways.[5] Gilbert had the idea of extending the canal underground to produce a navigable level in the coal measures that would drain the pits, keep the canal in water and transport the coal to market.[5][6] The Duke obtained the Act of Parliament authorising the Bridgewater Canal’s construction in March 1759.[5]

Underground levels

The underground canal network was started in 1759 from the rock face of the quarry at Worsley Delph and named “the Level”.[7][c]The Bridgewater Canal starts where the Navigable Levels exit the rock face at the Delph. Its eliptical entrance arch is 8 feet (2.4 m) wide and 82 feet (25 m) above sea level. Each yard of progress into the rock filled two boats with rubble. Stone from the quarry was used for canal bridges, and spoil from the Level was used for embankments on the canal. Spoil was also boated to Chat MossLarge area of peat bog that makes up 30 per cent of the City of Salford, in Greater Manchester, England, where it was spread at Botany Bay to reclaim the land.[7]

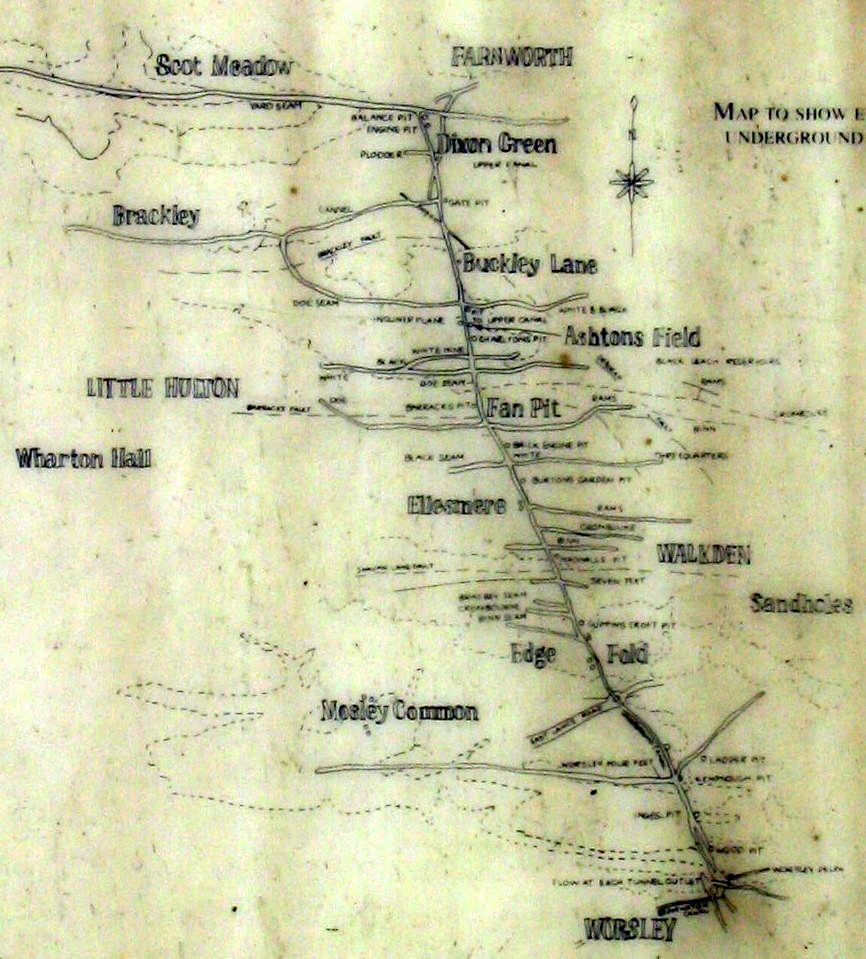

As the Main Level headed northwards through the coal measures towards Walkden, it intercepted the first workable coal 770 yards (704 m) from the entrance in 1761.[7] It drained the Worsley Four Foot mine that was above Massey’s Sough. The Level intercepted the coal seams at right angles, and more tunnels were driven into the coal and extended as the coal was extracted.[8]

In 1770 the Edge Fold Pit was deepened to the Level[9] when it passed the Parr Fold pits [d]About 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from Worsley Delph [10] and was close to Walkden. The first main branch off the Level headed west along the Four Foot mine towards Boothstown, and reached a length of one and three-quarter miles.[11] Coal was accessed by shafts sunk along the Main Level, providing access for colliers and materials. They included Wood Pit, Ingles Pit and Kempnough Pit in Worsley, Edge Fold Pits and Magnall’s Pit in Walkden.[12]

Throughout the 1760s the duke acquired leases, initially to safeguard the route of the Level but also to increase the reserves. He leased land in Farnworth to the north of his estate,[13] and at Deane. He intended to continue the Main Level north under Walkden Moor to Dixon Green in Farnworth. Work started in the Cannel mine following an old sough at Dixon Green and Watergate in Deane but the levels did not coincide. An Upper Level, 35 yards above the Main Level was driven and in the 1780s was one and three-quarter miles long, eventually reaching from Walkden to Plodder Lane.[14] When the Upper Level was driven, access for boats was via a “day eye” or adit in Walkden town centre. It was driven south with a gradient of 1 in 4 following the dip of the coal seams. It was equipped with rails and a cradle for hauling boats in and out.[15] A boat yard was developed and Boatshed reservoir provided storage.[16] In the 1780s pits were developed along the line of the Four Foot mine.[11]

As shallow coal seams were exhausted the Main Level was extended northwards, reaching Buckley Lane by 1800. Branch canals were driven eastwards to Linnyshaw and westwards towards Chaddock in Tyldesley.[14] Deep Navigable Levels were started before 1800 to transport coal from the the pit bottom of the deep pits, which was then wound either to the surface for sale locally or to the main Level.[14]

The Main Level was extremely busy. Boat traffic was congested particularly at Worsley Delph, and so in 1771 work started on a second entrance tunnel, which met the original tunnel about 500 yards (457 m) underground. The new tunnel was the exit for loaded boats, while empty boats used the original tunnel.[11]

Inclined plane

Workshops to build boats for the Upper Level were built in Walkden, and an adit, the Boatgate,[17] was driven to it for boat access.[14] So that boats could be transferred between levels, a subterranean inclined plane was constructed at Ashton’s Field, north of Walkden between 1795 and 1797.[16] John Gilbert who had overseen all the work on the underground Levels died as work started on the inclined plane.[18]

The inclined plane follows the 1 in 4 dip of the rock strata. [16] It occupies a cave blasted out of the rock by gunpowder and finished using hand tools. It is 151 yards long and 21 feet high above the brake wheel. Its double wagonway is 19 feet wide and laid with iron rails on sleepers. Two cradles, 30 feet long and 7 feet 4 inches wide, carried the Mine Boats between the Levels. The laden boats weighed about 21 tons, and more than 30 could be moved in eight hours.[19]

Bridgewater Trustees

The Duke of Bridgewater died in 1803, following which the collieries and canal were run by three trustees. The ChaddockPit sunk in about 1820 by the Bridgewater Trustees that was connected to the Bridgewater Canal at Boothstown Basin by an underground canal.Pit sunk in about 1820 by the Bridgewater Trustees that was connected to the Bridgewater Canal at Boothstown Basin by an underground canal. and Queen Anne Pits were sunk by 1820, and a second Navigable Level was driven to the Leigh branch of the Bridgewater Canal at Boothstown Basin.[20] At round the same time small landsale pits were sunk along the Manchester Road at Wardley but not connected to the Levels.[20] The City and Gatley Pits at New ManchesterFormerly isolated mining community at the extreme eastern end of the Tyldesley township. were sunk in the 1840s, and connected to the Levels.[21]

The trustees built a tramroad to transport coal from their pits around Ellenbrook to the Bridgewater Canal at Boothstown in the 1830s. The tramroad used gravity to transport coal to the canal and horses to pull the empty wagons uphill back to the pits.[20]

Extent

The Main Level and its branches extended for more than 23 miles (37 km), the Upper Level and branches for more than 9 miles (14 km), the Deep Levels for more than 14 miles (23 km), and the Chaddock Level in Boothstown and its branches more than 3 miles (5 km). [22] After 1760, shafts were sunk at various times along its length in Worsley, Walkden, Ellenbrook

Residential suburb of Worsley in the City of Salford in Greater Manchester, England., Dixon Green, Roe Green, ChaddockPit sunk in about 1820 by the Bridgewater Trustees that was connected to the Bridgewater Canal at Boothstown Basin by an underground canal.Pit sunk in about 1820 by the Bridgewater Trustees that was connected to the Bridgewater Canal at Boothstown Basin by an underground canal., Farnworth and Wardley for access to the Level for men and materials, ventilation, pumping and winding. In 1830 the colliery had 82 Mine Boats, 75 Tunnel Boats, 45 Boats in the Deep Levels, four steam engines, ten horse gins and nine tub engines. [23]

The colliery employed men, women and children before the 1842 Mines Act

Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom prohibiting all females and boys under ten years of age from working underground in coal mines.

was passed. Men worked as hewers, tunnellers or boatmen, women, boys and girls worked as drawers moving sledges from the coal face to the Level.

In 1853 in returns made to the Mines Inspectorate, the Bridgewater Trustees reported the existence of 25 working pits, and 37 abandoned pits that had been fenced off. The trustees employed about 1100 men and boys in the pits, who raised 274,380 tons of coal in 1852. [21]

Decline

By the mid-19th century the shallow reserves were worked out and the economic workings were more than 100 yards (91 m) deep. Ashton’s Field Colliery was started near the inclined plane in 1853 and deepened several times, eventually reaching a depth of 500 yards (457 m). Ellesmere CollieryEllesmere Colliery in Walkden, on the Lancashire Coalfield, was sunk in 1865 by the Bridgewater Trustees. Production ended in 1923. was sunk in the centre of Walkden in 1865. [24] After 1887 the Main Level was no longer used to transport coal, but continued in use as a giant sough to drain the workings of the Bridgewater Coal mining company on the Lancashire Coalfield with headquarters in Walkden near Manchester. pits until Mosley Common Colliery closed in 1968.[25]

Notes

| a | In Lancashire a coal seam is referred to as a mine, and the coal mine as a colliery or pit. |

|---|---|

| b | A sough is a tunnel or adit. The Great Haigh SoughTunnel or adit driven under Sir Roger Bradshaigh’s Haigh Hall estate between 1653 and 1670, to drain his coal and cannel pits. at Haigh Near Wigan had been constructed between 1653 and finished in 1670. |

| c | The Bridgewater Canal starts where the Navigable Levels exit the rock face at the Delph. |

| d | About 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from Worsley Delph [10] |