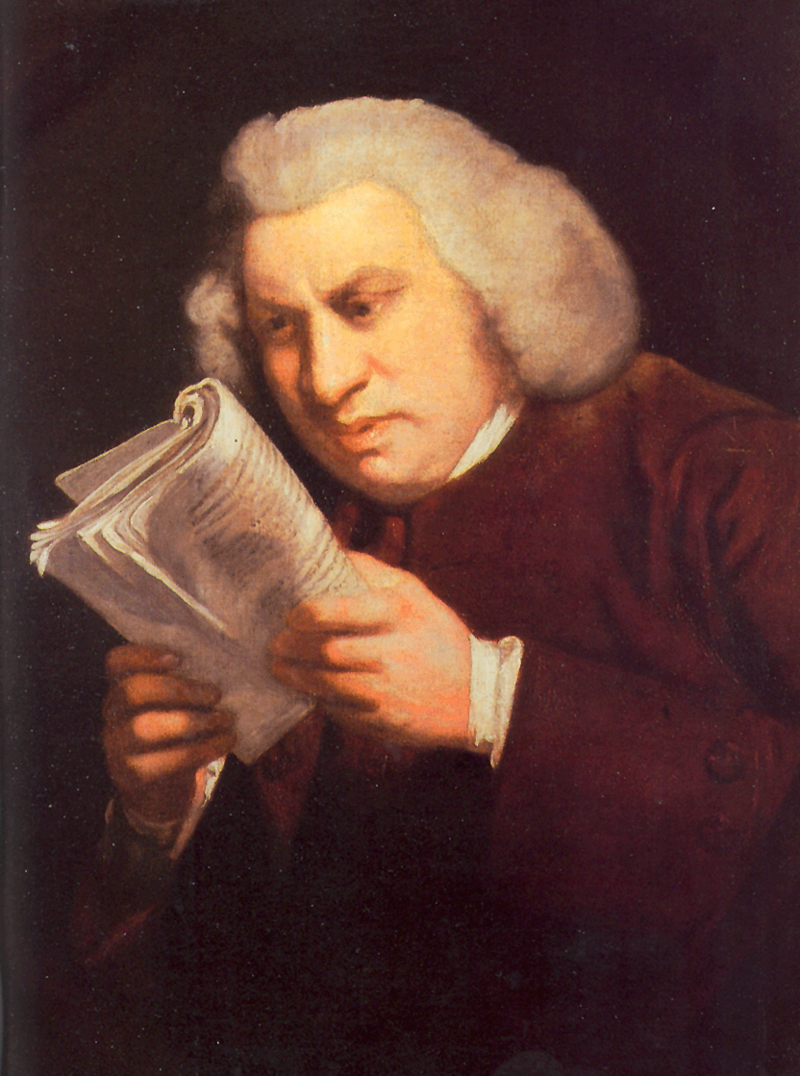

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 [OS 7 September] – 13 December 1784), often referred to as Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions to the language as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. He was a devout Anglican,[1] committed Tory, and “arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history”.[2]

Born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, he attended Pembroke College, Oxford until lack of funds forced him to leave. After work as a teacher, he moved to London and began writing for The Gentleman’s MagazineMonthly compendium of the best news, essays and information from the daily and weekly newspapers, published from 1731 until 1914.. Early works include Life of Mr Richard Savage, the poems London and The Vanity of Human Wishes and the play Irene. After nine years’ effort, Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language appeared in 1755 with far-reaching effects on Modern English, acclaimed as “one of the greatest single achievements of scholarship”.[3] Until the arrival of the Oxford English Dictionary 150 years later, Johnson’s was pre-eminent.[4] Later work included essays, an annotated The Plays of William Shakespeare and The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia. In 1763 he befriended James Boswell, with whom he travelled to Scotland, as Johnson described in A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland. Near the end of his life came a massive, influential Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets of 17th and 18th centuries.

Tall and robust, he displayed gestures and tics that disconcerted some on meeting him. Boswell’s Life, along with other biographies, documented Johnson’s behaviour and mannerisms in such detail that they have informed the posthumous diagnosis of Tourette syndrome,[5][6] a condition not recognised in the 18th century. After several illnesses he died on the evening of 13 December 1784, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Early life and education

Samuel Johnson was born on 18 September 1709, to Sarah (née Ford) and Michael Johnson, a bookseller.[7] The birth took place in the family home above his father’s bookshop in Lichfield, Staffordshire. His mother was forty when she gave birth, considered an unusually late pregnancy, so a “man-midwife” and surgeon of “great reputation” named George Hector was brought in to assist.[8] The infant Johnson did not cry, and there were concerns for his health. His aunt exclaimed that “she would not have picked such a poor creature up in the street”.[9] The family feared that Johnson would not survive, and summoned the vicar of St Mary’s to perform a baptism.[10] Two godfathers were chosen, Samuel Swynfen, a physician and graduate of Pembroke College, Oxford, and Richard Wakefield, a lawyer, coroner, and Lichfield town clerk.[11]

Johnson’s health improved and he was put to wet-nurse with Joan Marklew. Some time later he contracted scrofula,[12] known at the time as the King’s EvilName given in medieval times to scrofula, a swelling of the lymph nodes in the neck caused by tuberculosis., because it was thought that royalty could cure it. Sir John Floyer, former physician to King Charles II, recommended that the young Johnson should receive the “royal touch”,[13] and he did so from Queen Anne on 30 March 1712. But the ritual proved ineffective, and an operation was performed that left him with permanent scars across his face and body.[14] Following the birth of Johnson’s brother Nathaniel a few months later, their father was unable to pay the debts he had accrued over the years, and the family was no longer able to maintain its standard of living.[15]

| When he was a child in petticoats, and had learnt to read, Mrs. Johnson one morning put the common prayer-book into his hands, pointed to the collect for the day, and said, ‘Sam, you must get this by heart.’ She went up stairs, leaving him to study it: But by the time she had reached the second floor, she heard him following her. ‘What’s the matter?’ said she. ‘I can say it,’ he replied; and repeated it distinctly, though he could not have read it more than twice. — Boswell’s Life of Johnson[16] |

Johnson displayed signs of great intelligence as a child, and his parents, to his later disgust, would show off his “newly acquired accomplishments”.[17] His education began at the age of three, and was provided by his mother, who had him memorise and recite passages from the Book of Common Prayer.[18] When Samuel turned four, he was sent to a nearby school, and, at the age of six he was sent to a retired shoemaker to continue his education.[19] A year later Johnson went to Lichfield Grammar School, where he excelled in Latin.[20] During this time, Johnson started to exhibit the tics that would influence how people viewed him in his later years, and which formed the basis for a posthumous diagnosis of Tourette syndrome.[21] He excelled at his studies and was promoted to the upper school at the age of nine.[20] During this time he befriended Edmund Hector, nephew of his “man-midwife” George Hector, and John Taylor, with whom he remained in contact for the rest of his life.[22]

At the age of 16 Johnson stayed with his cousins, the Fords, at Pedmore, Worcestershire.[23] There he became a close friend of Cornelius Ford, who employed his knowledge of the classics to tutor Johnson while he was not attending school.[24] Ford was a successful, well-connected academic, and notorious alcoholic whose excesses contributed to his death six years later.[25] After spending six months with his cousins, Johnson returned to Lichfield, but Mr Hunter, the headmaster, “angered by the impertinence of this long absence”, refused to allow Johnson to continue at the school.[26] Unable to return to Lichfield Grammar School, Johnson enrolled at the King Edward VI grammar school at Stourbridge.[24] As the school was near Pedmore, Johnson was able to spend more time with the Fords, and he began to write poems and verse translations.[26] But he spent only six months at Stourbridge before returning once again to his parent’s home in Lichfield.[27]

During this time Johnson’s future remained uncertain, because his father was deeply in debt.[28] To earn money, Johnson began to stitch books for his father, and it is likely that Johnson spent much time in his father’s bookshop reading and building his literary knowledge. The family remained in poverty until his mother’s cousin Elizabeth Harriotts died in February 1728 and left enough money to send Johnson to university.[29] On 31 October 1728, a few weeks after he turned 19, Johnson entered Pembroke College, Oxford.[30] The inheritance did not cover all of his expenses at Pembroke, and Andrew Corbet, a friend and fellow student at the college, offered to make up the deficit.[31]

Johnson made friends at Pembroke and read much, but in later life he told stories of his idleness. His tutor asked him to produce a Latin translation of Alexander Pope’s Messiah as a Christmas exercise.[32] Johnson completed half of the translation in one afternoon and the rest the following morning. Although the poem brought him praise, it did not bring the material benefit he had hoped for.[33] It subsequently appeared in Miscellany of Poems (1731), edited by John Husbands, a Pembroke tutor, and is the earliest surviving publication of any of Johnson’s writings. Johnson spent the rest of his time studying, even during the Christmas holiday. He drafted a “plan of study” called “Adversaria”, which he left unfinished, and used his time to learn French while working on his Greek.[34]

After thirteen months, a lack of funds forced Johnson to leave Oxford without a degree, and he returned to Lichfield.[29] Towards the end of Johnson’s stay at Oxford, his tutor, Jorden, left Pembroke and was replaced by William Adams. Johnson enjoyed Adams’ tutoring, but by December he was already a quarter behind in his student fees, and forced to return home. He left behind many books he had borrowed from his father because he could not afford to transport them, and also because he hoped to return to Oxford.[35]

Johnson did eventually receive a degree. Just before the publication of his Dictionary in 1755, the University of Oxford awarded him the degree of Master of Arts.[36] He was also awarded an honorary doctorate in 1765 by Trinity College Dublin and in 1775 by the University of Oxford.[37] In 1776 he returned to Pembroke with Boswell and toured the college with his former tutor Adams, who by then was the Master of the college. During that visit he recalled his time at the college and his early career, and expressed his later fondness for Jorden.[38]

Early career

Little is known about Johnson’s life between the end of 1729 and 1731, but it is likely that he lived with his parents. He experienced bouts of mental anguish and physical pain during years of illness;[39] his tics and gesticulations associated with Tourette syndrome became more noticeable and were often commented upon.[40] By 1731 Johnson’s father was deeply in debt and had lost much of his standing in Lichfield. Johnson hoped to get an usher’s position, which became available at Stourbridge Grammar School, but since he did not have a degree, his application was passed over on 6 September 1731.[39] At about this time, Johnson’s father became ill and developed an “inflammatory fever”, which led to his death in December 1731.[41] Johnson eventually found employment as undermaster at a school in Market Bosworth, run by Sir Wolstan Dixie, who allowed him to teach even though he had no degree.[42] Although Johnson was treated as a servant,[43] he found pleasure in teaching, despite considering it boring. After an argument with Dixie he left the school, and by June 1732 he had returned home.[44]

Johnson continued to look for a position at a Lichfield school. After being turned down for a job at Ashbourne, he spent time with his friend Edmund Hector, who was living in the home of the publisher Thomas Warren. At the time, Warren was starting his Birmingham Journal, and he enlisted Johnson’s help.[45] This connection with Warren grew, and Johnson proposed a translation of Jerónimo Lobo’s account of the Abyssinians.[46] Johnson read Abbé Joachim Le Grand’s French translations, and thought that a shorter version might be “useful and profitable”.[47] Instead of writing the work himself, he dictated to Hector, who then took the copy to the printer and made any corrections. Johnson’s A Voyage to Abyssinia was published a year later.[47] He returned to Lichfield in February 1734 and began an annotated edition of Poliziano’s Latin poems, along with a history of Latin poetry from Petrarch to Poliziano; a Proposal was soon printed, but a lack of funds halted the project.[48]

Johnson remained with his close friend Harry Porter during a terminal illness,[49] which ended in Porter’s death on 3 September 1734. Porter’s wife Elizabeth (née Jervis) (otherwise known as “Tetty”) was now a widow at the age of forty-five, with three children.[50] Some months later, Johnson began to court her. The Reverend William Shaw claims that “the first advances probably proceeded from her, as her attachment to Johnson was in opposition to the advice and desire of all her relations”.[51] Johnson was inexperienced in such relationships, but the well-to-do widow encouraged him and promised to provide for him with her substantial savings.[52] They married on 9 July 1735, at St Werburgh’s Church in Derby.[53] The Porter family did not approve of the match, partly because of the difference in their ages; Johnson was twenty-five and Elizabeth was forty-six. Elizabeth’s marriage to Johnson so disgusted her son Jervis that he severed all relations with her.[54] But her daughter Lucy accepted Johnson from the start, and Elizabeth’s other son, Joseph, later came to accept the marriage.[55]

In June 1735, while working as a tutor for the children of Thomas Whitby, a local Staffordshire gentleman, Johnson had applied for the position of headmaster at Solihull School.[56] Although Johnson’s friend Gilbert Walmisley gave his support, Johnson was passed over because the school’s directors thought he was “a very haughty, ill-natured gent, and that he has such a way of distorting his face (which though he can’t help) the gents think it may affect some lads”.[57] With Walmisley’s encouragement, Johnson decided that he could be a successful teacher if he ran his own school.[58] Towards the end of 1735 Johnson opened Edial Hall School as a private academy at Edial, near Lichfield. He had only three pupils: Lawrence Offley, George Garrick, and the 18-year-old David Garrick, who was to become one of the most famous actors of his day.[57] The venture was unsuccessful and cost Tetty a substantial portion of her fortune. Instead of trying to keep the failing school going, Johnson began to write his first major work, the historical tragedy Irene.[59] The biographer Robert DeMaria believed that Tourette syndrome likely made public occupations like schoolmaster or tutor almost impossible for Johnson. This may have led Johnson to “the invisible occupation of authorship”.[21]

Johnson left for London with his former pupil David Garrick on 2 March 1737, the day Johnson’s brother died. He was penniless and pessimistic about their travel, but fortunately for them, Garrick had connections in London, and the two were able to stay with his distant relative, Richard Norris.[60] Johnson soon moved to Greenwich near the Golden Hart Tavern to finish Irene.[63] On 12 July 1737 he wrote to Edward Cave with a proposal for a translation of Paolo Sarpi’s The History of the Council of Trent (1619), which Cave did not accept until months later.[61][62] In October 1737 Johnson brought his wife to London, and he found employment with Cave as a writer for The Gentleman’s MagazineMonthly compendium of the best news, essays and information from the daily and weekly newspapers, published from 1731 until 1914..[63] His assignments for the magazine and other publishers during this time were “almost unparalleled in range and variety,” and “so numerous, so varied and scattered” that “Johnson himself could not make a complete list”.[64]

In May 1738 Johnson’s first major work, the poem London, was published anonymously.[65] Based on Juvenal’s Satire III, it describes the character Thales leaving for Wales to escape the problems of London,[66] which is portrayed as a place of crime, corruption, and poverty. Johnson could not bring himself to regard the poem as earning him any merit as a poet.[67] Alexander Pope said that the author “will soon be déterré” (unearthed, dug up), but that did not happen until fifteen years later.[65]

In August, Johnson’s lack of an MA degree from Oxford or Cambridge led to his being denied a position as master of the Appleby Grammar School. In an effort to end such rejections, Pope asked Lord Gower to use his influence to have a degree awarded to Johnson.[9] Gower petitioned Oxford for an honorary degree to be awarded to Johnson, but was told that it was “too much to be asked”. Gower then asked a friend of Jonathan Swift to plead with Swift to use his influence at the University of Dublin to have a master’s degree awarded to Johnson, in the hope that this could then be used to justify an MA from Oxford,[68] but Swift refused to act on Johnson’s behalf.[69]

Between 1737 and 1739, Johnson befriended poet Richard Savage.[70] Feeling guilty of living almost entirely on Tetty’s money, Johnson stopped living with her and spent his time with Savage. They were poor and would stay in taverns or sleep in “night-cellars”. Some nights they would roam the streets until dawn because they had no money.[71] Savage’s friends tried to help him by attempting to persuade him to move to Wales, but Savage ended up in Bristol and again fell into debt. He was committed to debtors’ prison and died in 1743. A year later, Johnson wrote the Life of Mr Richard Savage (1744), a “moving” work which, in the words of the biographer and critic Walter Jackson Bate, “remains one of the innovative works in the history of biography”.[72]

A Dictionary of the English Language

In 1746 a group of publishers approached Johnson with an idea about creating an authoritative dictionary of the English language.[65] A contract with William Strahan and associates, worth 1,500 guineas, equivalent to about £250,000 as at 2020,[a]Using the retail price index measure of inflation.[73] was signed on the morning of 18 June 1746.[74] Johnson claimed that he could finish the project in three years. In comparison, the Académie Française had forty scholars spending forty years to complete their dictionary, which prompted Johnson to claim, “This is the proportion. Let me see; forty times forty is sixteen hundred. As three to sixteen hundred, so is the proportion of an Englishman to a Frenchman.” Although he did not succeed in completing the work in three years, he did manage to finish it in eight.[65] Some criticised the work, including Thomas Babington Macaulay, who described Johnson as “a wretched etymologist,”[75] but according to Bate, the Dictionary “easily ranks as one of the greatest single achievements of scholarship, and probably the greatest ever performed by one individual who laboured under anything like the disadvantages in a comparable length of time.”[3] Published in 1755, Johnson’s dictionary was not the first, nor was it unique, but it was the most commonly used and imitated for the 150 years between its first publication and the completion of the Oxford English Dictionary in 1928.[4]

Tetty Johnson was ill during most of her time in London, and in 1752 she decided to return to the countryside while Johnson was busy working on his Dictionary. She died on 17 March 1752.[76] Johnson felt guilty about the poverty in which he believed he had forced Tetty to live, and blamed himself for neglecting her. She had been his primary motivation, and her death interfered greatly with his continuing ability to work productively.[77]

In 1762 the 24-year-old King George III granted Johnson an annual pension of £300 in appreciation for the Dictionary,[37] equivalent to about £47,600 as at 2021,[b]Using the retail price index measure of inflation,[73] which allowed him a modest yet comfortable independence for the remaining twenty-two years of his life.[78] When Johnson questioned if the pension would force him to promote a political agenda or support various officials, he was told that the pension “is not given you for anything you are to do, but for what you have done”.[79]

Later career

On 16 March 1756, less than a year after the publication of his Dictionary, Johnson was arrested for an outstanding debt of £5 18s, equivalent to about £900 as at 2021.[c]Using the retail price index measure of inflation.[73]. Unable to contact anyone else, he wrote to the writer and publisher Samuel Richardson. Richardson, who had previously lent Johnson money, sent him six guineas to show his good will, and the two became friends.[80] Soon after, Johnson met and befriended the painter Joshua Reynolds, who so impressed Johnson that he declared him “almost the only man whom I call a friend”.[81] Reynolds’ younger sister Frances observed during their time together “that men, women and children gathered around him [Johnson]”, laughing at his gestures and gesticulations.[82] In addition to Reynolds, Johnson was close to Bennet Langton and Arthur Murphy. Langton was a scholar and an admirer of Johnson who persuaded his way into a meeting with Johnson which led to a long friendship. Johnson met Murphy during the summer of 1754 after Murphy came to Johnson about the accidental republishing of the Rambler No. 190, and the two became friends.[83] Around this time, Anna Williams began boarding with Johnson. She was a minor poet who was poor and becoming blind, two conditions that Johnson attempted to change by providing room for her and paying for a failed cataract surgery. Williams, in turn, became Johnson’s housekeeper.[84]

To occupy himself, Johnson began to work on The Literary Magazine, or Universal Review, the first issue of which was printed on 19 March 1756. Philosophical disagreements erupted over the purpose of the publication when the Seven Years’ War began and Johnson started to write polemical essays attacking the war. After the war began, the Magazine included many reviews, at least 34 of which were written by Johnson.[85] When not working on the Magazine, Johnson wrote a series of prefaces for other writers, including Giuseppe Baretti, William Payne and Charlotte Lennox.[86] Johnson’s relationship with Lennox and her works was particularly close during these years, and she in turn relied so heavily upon Johnson that he was “the most important single fact in Mrs Lennox’s literary life”.[87] He later attempted to produce a new edition of her works, but even with his support they were unable to find enough interest to follow through with its publication.[88] To help with domestic duties while Johnson was busy with his various projects, Richard Bathurst, a physician and a member of Johnson’s Club, pressured him to take on a freed slave, Francis Barber, as his servant.[89]

Johnson’s work on The Plays of William Shakespeare took up most of his time. On 8 June 1756, Johnson published his Proposals for Printing, by Subscription, the Dramatick Works of William Shakespeare, which argued that previous editions of Shakespeare were edited incorrectly and needed to be corrected.[90] Johnson’s progress on the work slowed as the months passed, and he told music historian Charles Burney in December 1757 that it would take him until the following March to complete it. Before that could happen, he was arrested again, for a debt of £40, in February 1758. The debt was soon repaid by Jacob Tonson, who had contracted Johnson to publish Shakespeare, and this encouraged Johnson to finish his edition to repay the favour. Although it took him another seven years to finish, Johnson completed a few volumes of his Shakespeare to prove his commitment to the project.[91]

In 1758 Johnson began to write a weekly series, The Idler, which ran from 15 April 1758 to 5 April 1760, as a way to avoid finishing his Shakespeare. This series was shorter and lacked many features of The Rambler. Unlike his independent publication of The Rambler, The Idler was published in a weekly news journal, The Universal Chronicle, a publication supported by John Payne, John Newbery, Robert Stevens and William Faden.[92]

The Idler did not occupy all of Johnson’s time, so he was able to publish his philosophical novella Rasselas on 19 April 1759. The “little story book”, as Johnson described it, describes the life of Prince Rasselas and Nekayah, his sister, who are kept in a place called the Happy Valley in the land of Abyssinia. The Valley is a place free of problems, where any desire is quickly satisfied. But the constant pleasure does not lead to satisfaction, and with the help of a philosopher named Imlac, Rasselas escapes and explores the world to witness how all aspects of society and life in the outside world are filled with suffering. They return to Abyssinia, but do not wish to return to the state of constantly fulfilled pleasures found in the Happy Valley.[93] Rasselas was written in one week to pay for his mother’s funeral and settle her debts; it became so popular that there was a new English edition of the work almost every year. References to it appear in many later works of fiction, including Jane Eyre, Cranford and The House of the Seven Gables. Its fame was not limited to English-speaking nations: Rasselas was immediately translated into five languages (French, Dutch, German, Russian and Italian), and later into nine others.[94]

By 1762 Johnson had gained notoriety for his dilatoriness in writing; the contemporary poet Churchill teased Johnson for the delay in producing his long-promised edition of Shakespeare: “He for subscribers baits his hook / and takes your cash, but where’s the book?” The comments soon motivated Johnson to finish his Shakespeare, and, after receiving the first payment from his government pension on 20 July 1762, he was able to dedicate most of his time towards this goal.[95]

On 16 May 1763, Johnson first met 22-year-old James Boswell – who became Johnson’s first major biographer – in the bookshop of Johnson’s friend, Tom Davies. They quickly became friends, although Boswell would return to his home in Scotland or travel abroad for months at a time.[96] In early 1763 Johnson formed “The Club”, a social group that included his friends Reynolds, Burke, Garrick, Goldsmith and others (the membership later expanded to include Adam Smith and Edward Gibbon, in addition to Boswell himself). They decided to meet every Monday at 7:00 pm at the Turk’s Head in Gerrard Street, Soho, and these meetings continued until long after the deaths of the original members.[97]

Wikimedia Commons

On 9 January 1765 Murphy introduced Johnson to Henry Thrale, a wealthy brewer and MP, and his wife Hester. They struck up an instant friendship; Johnson was treated as a member of the family, and was once more motivated to continue working on his Shakespeare.[98] Afterwards, Johnson stayed with the Thrales for seventeen years until Henry’s death in 1781, sometimes staying in rooms at Thrale’s Anchor Brewery in Southwark.[99] Hester Thrale’s documentation of Johnson’s life during this time, in her correspondence and her diary (Thraliana), became an important source of biographical information on Johnson after his death.[100]

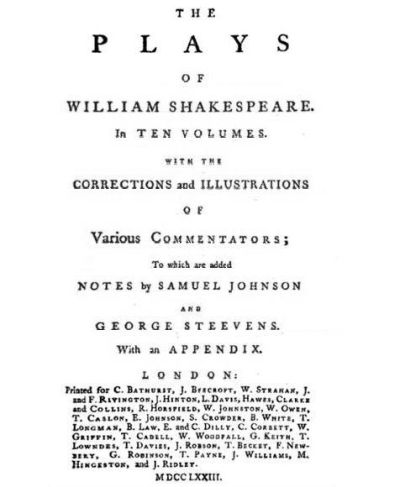

Johnson’s edition of Shakespeare was finally published on 10 October 1765 as The Plays of William Shakespeare, in Eight Volumes … To which are added Notes by Sam. Johnson in a printing of one thousand copies. The first edition quickly sold out, and a second was soon printed.[101] The plays themselves were in a version that Johnson felt was closest to the original, based on his analysis of the manuscript editions. Johnson’s revolutionary innovation was to create a set of corresponding notes that allowed readers to clarify the meaning behind many of Shakespeare’s more complicated passages, and to examine those which had been transcribed incorrectly in previous editions.[102] Included within the notes are occasional attacks upon rival editors of Shakespeare’s works.[103] Years later, Edmond Malone, an important Shakespearean scholar and friend of Johnson’s, stated that Johnson’s “vigorous and comprehensive understanding threw more light on his authour than all his predecessors had done”.[104]

| During the whole of the interview, Johnson talked to his Majesty with profound respect, but still in his firm manly manner, with a sonorous voice, and never in that subdued tone which is commonly used at the levee and in the drawing-room. After the King withdrew, Johnson shewed himself highly pleased with his Majesty’s conversation and gracious behaviour. He said to Mr Barnard, ‘Sir, they may talk of the King as they will; but he is the finest gentleman I have ever seen.’ — Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson[105] |

In February 1767, Johnson was granted a special audience with King George III. This took place at the library of the Queen’s house, organised by Barnard, the King’s librarian. The King, upon hearing that Johnson would visit the library, commanded that Barnard introduce him to Johnson. After a short meeting, Johnson was impressed both with the King himself and with their conversation.[106]

Final works

Wikimedia Commons

On 6 August 1773, eleven years after first meeting Boswell, Johnson set out to visit his friend in Scotland, and begin “a journey to the western islands of Scotland”, as Johnson’s 1775 account of their travels would put it.[107] The work was intended to discuss the social problems and struggles that affected the Scottish people, but it also praised many of the unique facets of Scottish society, such as a school in Edinburgh for the deaf and mute.[108] Johnson also used the work to enter into the dispute over the authenticity of James Macpherson’s Ossian poems, claiming they could not have been translations of ancient Scottish literature on the grounds that “in those times nothing had been written in the Earse [i.e. Scots Gaelic] language”.[109] There were heated exchanges between the two, and according to one of Johnson’s letters, MacPherson threatened physical violence.[110] Boswell’s account of their journey, The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides (1786), was a preliminary step toward his later biography, The Life of Samuel Johnson. Included were various quotations and descriptions of events, including anecdotes such as Johnson swinging a broadsword while wearing Scottish garb, or dancing a Highland jig.[111]

Johnson had tended to be an opponent of the government in his earlier life, but in the 1770s he began to publish a series of pamphlets supporting various government policies. In 1770 he produced The False Alarm, a political pamphlet attacking John Wilkes. In 1771, his Thoughts on the Late Transactions Respecting Falkland’s Islands cautioned against war with Spain.[112] In 1774 he printed The Patriot, a critique of what he viewed as false patriotism; on the evening of 7 April 1775 he made the famous statement, “Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel.”[113] This line was not, as widely believed, about patriotism in general, but what Johnson considered to be the false use of the term “patriotism” by Wilkes and his supporters. Johnson opposed “self-professed Patriots” in general, but valued what he considered “true” patriotism.[114]

The last of these pamphlets, Taxation No Tyranny (1775), was a defence of the Coercive Acts and a response to the Declaration of Rights of the First Continental Congress, which protested against taxation without representation.[115] Johnson argued that in emigrating to America, colonists had “voluntarily resigned the power of voting”, but they still retained “virtual representation” in parliament. In a parody of the Declaration of Rights, Johnson suggested that the Americans had no more right to govern themselves than the Cornish, and asked “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?” If the Americans wanted to participate in parliament, said Johnson, they could move to England and purchase an estate.[116] Johnson denounced English supporters of American separatists as “traitors to this country”, and hoped that the matter would be settled without bloodshed, but he felt confident that it would end with “English superiority and American obedience”.[117] Years before, Johnson had stated that the French and Indian War was a conflict between “two robbers” of Native American lands, and that neither deserved to live there.[85] After the signing of the 1783 Treaty of Paris, marking the colonists’ victory over the British, Johnson became “deeply disturbed” with the “state of this kingdom”.[118]

On 3 May 1777, while Johnson was trying and failing to save the Reverend William Dodd from execution for forgery, he wrote to Boswell that he was busy preparing a “little Lives” and “little Prefaces, to a little edition of the English Poets”.[119] Tom Davies, William Strahan and Thomas Cadell had asked Johnson to create this final major work, the Lives of the English Poets, for which he asked 200 guineas, an amount significantly less than the price he could have demanded.[120] The Lives, which were critical as well as biographical studies, appeared as prefaces to selections of each poet’s work, and they were longer and more detailed than originally expected.[121] The work was finished in March 1781 and the whole collection was published in six volumes. As Johnson justified in the advertisement for the work, “my purpose was only to have allotted to every Poet an Advertisement, like those which we find in the French Miscellanies, containing a few dates and a general character.”[122]

Johnson was unable to enjoy this success, as Henry Thrale, the dear friend with whom he lived, died on 4 April 1781.[123] Life changed quickly for Johnson when Hester Thrale became romantically involved with the Italian singing teacher Gabriel Mario Piozzi, which forced Johnson to change his previous lifestyle.[124] After returning home and then travelling for a short period, Johnson received word that his friend and tenant, Robert Levet, had died on 17 January 1782.[125] Levet had lived in Johnson’s London home since 1762, and Johnson was shocked by his death.[126] Shortly afterwards Johnson caught a cold, which developed into bronchitis and lasted for several months. His health was further complicated by “feeling forlorn and lonely” over Levet’s death, and by the deaths of his friend Thomas Lawrence and his housekeeper Williams.[127]

Final years

Although he had recovered his health by August, he experienced emotional trauma when he was given word that Hester Thrale would sell the residence that Johnson shared with the family. What hurt Johnson most was the possibility that he would be left without her constant company.[128] Months later, on 6 October 1782, Johnson attended church for the final time, to say goodbye to his former residence and life. The walk to the church strained him, but he managed the journey unaccompanied.[129] While there, he wrote a prayer for the Thrale family:

Hester Thrale did not completely abandon Johnson, and asked him to accompany the family on a trip to Brighton.[129] He agreed, and was with them from 7 October to 20 November 1782.[131] On his return, his health began to fail, and he was left alone after Boswell’s visit on 29 May 1783.[132]

On 17 June 1783, Johnson’s poor circulation resulted in a stroke,[133] and he wrote to his neighbour, Edmund Allen, that he had lost the ability to speak.[134] Two doctors were brought in, and he regained his ability to speak two days later.[135] Johnson feared that he was dying, and wrote:

By this time he was sick and gout-ridden. He had surgery for gout, and his remaining friends, including novelist Fanny Burney (the daughter of Charles Burney), came to keep him company.[137] He was confined to his room from 14 December 1783 to 21 April 1784.[138]

Johnson’s health began to improve by May 1784, and he travelled to Oxford with Boswell on 5 May 1784.[138] By July, many of Johnson’s friends were either dead or gone; Boswell had left for Scotland and Hester Thrale had become engaged to Piozzi. With no one to visit, Johnson expressed a desire to die in London, where he arrived on 16 November 1784. On 25 November 1784 he allowed Burney to visit him, and expressed an interest to her that he should leave London; he soon left for Islington, to George Strahan’s home.[139] His final moments were filled with mental anguish and delusions; when his physician, Thomas Warren, visited and asked him if he were feeling better, Johnson burst out with: “No, Sir; you cannot conceive with what acceleration I advance towards death.”[140]

Many visitors came to see Johnson as he lay sick in bed, but he preferred only Langton’s company.[140] Burney waited for word of Johnson’s condition, along with Windham, Strahan, Hoole, Cruikshank, Des Moulins and Barber.[141] On 13 December 1784, Johnson met with two others: a young woman, Miss Morris, whom Johnson blessed, and Francesco Sastres, an Italian teacher, who was given some of Johnson’s final words: “Iam Moriturus” (“I who am about to die”).[142] Shortly afterwards he fell into a coma, and died at 7:00 p.m.[141]

Langton waited until 11:00 p.m. to tell the others, which led to John Hawkins’ becoming pale and overcome with “an agony of mind”, along with Seward and Hoole describing Johnson’s death as “the most awful sight”.[173] Boswell remarked, “My feeling was just one large expanse of Stupor … I could not believe it. My imagination was not convinced.”[142] William Gerard Hamilton joined in and stated, “He has made a chasm, which not only nothing can fill up, but which nothing has a tendency to fill up. –Johnson is dead.– Let us go to the next best: There is nobody; –no man can be said to put you in mind of Johnson.”[141]

Johnson was buried on 20 December 1784 at Westminster Abbey.[2]

Literary criticism

|  |

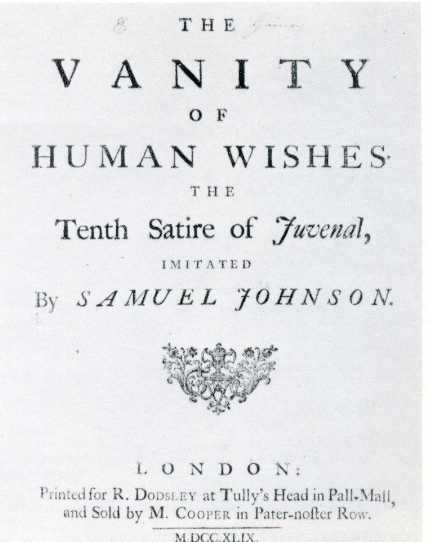

The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749) title page Wikimedia Commons | Plays of William Shakespeare (1773 expanded edition) title page Wikimedia Commons |

Johnson’s works, especially his Lives of the Poets series, describe various features of excellent writing. He believed that the best poetry relied on contemporary language, and he disliked the use of decorative or purposefully archaic language.[143] He was suspicious of the poetic language used by Milton, whose blank verse he believed would inspire many bad imitations. Also, Johnson opposed the poetic language of his contemporary Thomas Gray.[144] His greatest complaint was that obscure allusions found in works like Milton’s Lycidas were overused; he preferred poetry that could be easily read and understood.[145] In addition to his views on language, Johnson believed that a good poem incorporated new and unique imagery.[146]

In his smaller poetic works, Johnson relied on short lines and filled his work with a feeling of empathy, which possibly influenced Housman’s poetic style.[147] In London, his first imitation of Juvenal, Johnson uses the poetic form to express his political opinion and, as befits a young writer, approaches the topic in a playful and almost joyous manner.[148] However, his second imitation, The Vanity of Human Wishes, is completely different; the language remains simple, but the poem is more complicated and difficult to read because Johnson is trying to describe complex Christian ethics.[149] These Christian values are not unique to the poem, but contain views expressed in much of Johnson’s works; in particular, he emphasises God’s infinite love, and shows that happiness can be attained through virtuous action.[150]

Johnson disagreed with Plutarch’s use of biography to praise and to teach morality. Instead, he believed in portraying the biographical subjects accurately and including any negative aspects of their lives. Because his insistence on accuracy in biography was little short of revolutionary, Johnson had to struggle against a society that was unwilling to accept biographical details that could be viewed as tarnishing a reputation; this became the subject of Rambler 60.[151] In addition, Johnson believed that biography should not be limited to the most famous, and that the lives of lesser individuals were also significant;[152] thus in his Lives of the Poets he chose both great and lesser poets. In all his biographies he insisted on including what others would have considered trivial details to fully describe the lives of his subjects.[153] Johnson considered the genre of autobiography and diaries, including his own, as having the most significance; in Idler 84 he explains how a writer of an autobiography would be the least likely to distort his own life.[154]

Wikimedia Commons

Johnson’s thoughts on biography and on poetry coalesced in his understanding of what would make a good critic. His works were dominated with his intent to use them for literary criticism. This was especially true of his Dictionary of which he wrote: “I lately published a Dictionary like those compiled by the academies of Italy and France, for the use of such as aspire to exactness of criticism, or elegance of style“.[155] Although a smaller edition of his Dictionary became the standard household dictionary, Johnson’s original was an academic tool that examined how words were used, especially in literary works. To achieve this purpose, Johnson included quotations from Bacon, Hooker, Milton, Shakespeare, Spenser and many others from what he considered to be the most important literary fields: natural science, philosophy, poetry, and theology. These quotations and usages were all compared and carefully studied in the Dictionary so that a reader could understand what words in literary works meant in context.[156]

Johnson did not attempt to create schools of theories to analyse the aesthetics of literature. Instead, he used his criticism for the practical purpose of helping others to better read and understand it.[157] When it came to Shakespeare’s plays, Johnson emphasised the role of the reader in understanding language: “If Shakespeare has difficulties above other writers, it is to be imputed to the nature of his work, which required the use of common colloquial language, and consequently admitted many phrases allusive, elliptical, and proverbial, such as we speak and hear every hour without observing them”.[158]

Johnson’s works on Shakespeare were devoted not merely to the bard himself, but to understanding literature as a whole; in his Preface to Shakespeare, Johnson rejects the previous dogma of the classical unities and argues that drama should be faithful to life.[159] But Johnson did not only defend Shakespeare, he also discussed his faults, including his lack of morality, his vulgarity, his carelessness in crafting plots, and his occasional inattentiveness when choosing words or word order.[160] As well as direct literary criticism, Johnson emphasised the need to establish a text that accurately reflects what an author wrote. Shakespeare’s plays, in particular, had multiple editions, each of which contained errors resulting from the printing process. The problem was compounded by careless editors who deemed difficult words incorrect, and changed them in later editions. Johnson believed that an editor should not alter the text in such a way.[161]

Character sketch

Johnson’s tall[d]Johnson was 180 cm (5 feet 11 inches) tall, when the average height of an Englishman was 165 cm (5 feet 5 inches).[162] and robust figure combined with his odd gestures were confusing to some; when William Hogarth first saw Johnson standing near a window in Richardson’s house, “shaking his head and rolling himself about in a strange ridiculous manner”, Hogarth thought him an “ideot, whom his relations had put under the care of Mr. Richardson”.[163] Hogarth was quite surprised when “this figure stalked forwards to where he and Mr. Richardson were sitting and all at once took up the argument … [with] such a power of eloquence, that Hogarth looked at him with astonishment, and actually imagined that this ideot had been at the moment inspired”.[163] Beyond appearance, Adam Smith claimed that “Johnson knew more books than any man alive”,[164] and Edmund Burke thought that if Johnson were to join Parliament, he “certainly would have been the greatest speaker that ever was there”.[165] Johnson employed a unique form of rhetoric, and is well known for his refutation of Bishop Berkeley’s immaterialism, the idea that matter does not actually exist but only seems to exist;[166] during a conversation with Boswell, Johnson kicked a nearby stone and proclaimed of Berkeley’s theory, “I refute it thus!”[167]

Johnson was a devout conservative Anglican and a compassionate man who supported a number of poor friends under his own roof, even when unable to fully provide for himself.[37] Johnson’s Christian morality permeated his works, and he would write on moral topics with such authority and in such a trusting manner that, Walter Jackson Bate claims, “no other moralist in history excels or even begins to rival him”.[168] But Johnson’s moral writings do not contain, as Donald Greene points out, “a predetermined and authorized pattern of ‘good behavior’ ”, even though Johnson does emphasise certain kinds of conduct.[169] He did not allow his own faith to prejudice him against others, and had respect for those of other denominations who demonstrated a commitment to Christ’s teachings.[170] Although Johnson respected Milton’s poetry, he could not tolerate his Puritan and Republican beliefs, feeling that they were contrary to England and Christianity.[171] He was an opponent of slavery on moral grounds, and once proposed a toast to the “next rebellion of the negroes in the West Indies”.[172] Johnson was also known for his love of cats, especially his own two, Hodge and Lily;[173] Boswell wrote, “I never shall forget the indulgence with which he treated Hodge, his cat.[174]

Johnson was also known as a staunch Tory, and admitted to sympathising with the Jacobite cause during his younger years, but by the reign of George III he had come to accept the Hanoverian Succession.[171] It was Boswell more than anyone else who determined how Johnson would be seen by later generations, but he was absent for two of Johnson’s most politically active periods: during Walpole’s control over the British Parliament, and the Seven Years’ War.[175]

In his Life of Samuel Johnson, Boswell referred to Johnson as “Dr. Johnson” so often that the name stuck, even though Johnson disliked being referred to as such. Boswell’s emphasis on Johnson’s later years shows him too often as merely an old man discoursing in a tavern to a circle of admirers.[176] Although Boswell, a Scotsman, was a close companion and friend to Johnson during many important times of his life, like many of his fellow Englishmen Johnson had a reputation for despising Scotland and its people. Even during their journey together through Scotland, Johnson “exhibited prejudice and a narrow nationalism”.[177] Hester Thrale, in summarising Johnson’s nationalist views and his anti-Scottish prejudice, wrote: “We all know how well he loved to abuse the Scotch, & indeed to be abused by them in return.”[178]

Legacy

Wikimedia Commons

Johnson was, in the words of Steven Lynn, “more than a well-known writer and scholar”;[179] he was a celebrity. His activities and the state of his health in his later years were constantly reported on in various journals and newspapers, and when there was nothing to report, something was invented.[180] According to Bate, “Johnson loved biography,” and he “changed the whole course of biography for the modern world. One by-product was the most famous single work of biographical art in the whole of literature, Boswell’s Life of Johnson, and there were many other memoirs and biographies of a similar kind written about Johnson after his death.”[181] These accounts of his life include Thomas Tyers’s A Biographical Sketch of Dr Samuel Johnson (1784);[182] Boswell’s The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides (1785); Hester Thrale’s Anecdotes of the Late Samuel Johnson, which drew on entries from her diary and other notes;[183] John Hawkins’s Life of Samuel Johnson, the first full-length biography of Johnson;[184] and, in 1792, Arthur Murphy’s An Essay on the Life and Genius of Samuel Johnson, which replaced Hawkins’s biography as the introduction to a collection of Johnson’s Works.[185] Another important source was Fanny Burney, who described Johnson as “the acknowledged Head of Literature in this kingdom” and kept a diary containing details missing from other biographies.[186] Above all, Boswell’s portrayal of Johnson is the work best-known to general readers. Although critics like Donald Greene argue about its status as a true biography, the work became successful as Boswell and his friends promoted it at the expense of the many other works on Johnson’s life.[187]

Johnson had a lasting influence on literary criticism, although not everyone viewed him favourably. Some, like Macaulay, regarded Johnson as an idiot savant who produced some respectable works, while others, like the Romantic poets, were completely opposed to Johnson’s views on poetry and literature, especially with regard to Milton.[188] But some of their contemporaries disagreed; Stendhal’s Racine et Shakespeare is based in part on Johnson’s views of Shakespeare,[159] and Johnson influenced Jane Austen’s writing style and philosophy.[189] Later, Johnson’s works came into favour, and Matthew Arnold, in his Six Chief Lives from Johnson’s “Lives of the Poets”, considered the Lives of Milton, Dryden, Pope, Addison, Swift, and Gray as “points which stand as so many natural centres, and by returning to which we can always find our way again”.[190]

More than a century after his death, literary critics such as G. Birkbeck Hill and T. S. Eliot came to regard Johnson as a serious critic. They began to study Johnson’s works with an increasing focus on the critical analysis found in his edition of Shakespeare and Lives of the Poets.[188] Yvor Winters claimed that “A great critic is the rarest of all literary geniuses; perhaps the only critic in English who deserves that epithet is Samuel Johnson”.[191] F. R. Leavis agreed, and on Johnson’s criticism, said, “When we read him we know, beyond question, that we have here a powerful and distinguished mind operating at first hand upon literature. This, we can say with emphatic conviction, really is criticism”.[192] Edmund Wilson claimed that “The Lives of the Poets and the prefaces and commentary on Shakespeare are among the most brilliant and the most acute documents in the whole range of English criticism”.[191]

The critic Harold Bloom placed Johnson’s work firmly within the Western canon, describing him as “unmatched by any critic in any nation before or after him … Bate in the finest insight on Johnson I know, emphasised that no other writer is so obsessed by the realisation that the mind is an activity, one that will turn to destructiveness of the self or of others unless it is directed to labour.”[193] It is no wonder that his philosophical insistence that the language within literature must be examined became a prevailing mode of literary theory during the mid-20th century.[194]

Notes

References

- p. 2

- p. 240

- p. 1

- p. 5

- pp. 15–16

- p. 25

- p. 16

- pp. 5–6

- pp. 16–17

- p. 18

- pp. 19–20

- pp. 20–21

- p. 38

- pp. 18–19

- p. 21

- pp. 25–26

- p. 26

- pp. 5–6

- pp. 23, 31

- p. 29

- p. 32

- p. 30

- p. 33

- p. 61

- p. 34

- p. 87

- p. 39

- p. 88

- pp. 91–92

- p. 92

- pp. 93–94

- pp. 106–107

- pp. 128–129

- p. 36

- p. 99

- p. 127

- p. 24

- p. 129

- pp. 130–131

- p. 53

- pp. 131–132

- p. 134

- pp. 137–138

- p. 138

- pp. 140–141

- p. 144

- p. 143

- p. 88

- p. 145

- p. 147

- p. 65

- p. 146

- pp. 153–154

- p. 154

- p. 153

- p. 156

- pp. 164–165

- p. 81

- p. 169

- pp. 169–170

- p. 14

- p. 5

- p. 172

- p. 18

- p. 182

- pp. 25–26

- p. 51

- pp. 178–179

- pp. 180–181

- p. 58

- p. 33

- pp. 272–273

- pp. 273–275

- p. 356

- pp. 354–356

- p. 321

- p. 324

- p. 1611

- pp. 322–323

- p. 319

- p. 328

- p. 329

- pp. 221–222

- pp. 223–224

- pp. 325–326

- p. 330

- p. 332

- p. 334

- pp. 337–338

- p. 337

- p. 391

- p. 360

- p. 366

- p. 393

- p. 262

- p. 186

- p. 395

- p. 397

- p. 194

- p. 396

- p. 135

- pp. 133–135

- p. 463

- p. 471

- pp. 104–105

- p. 331

- pp. 468–469

- pp. 443–445

- p. 182

- p. 21

- p. 446

- p. 13

- pp. 252–256

- p. 15

- p. 525

- p. 526

- p. 527

- p. 161

- pp. 546–547

- pp. 557, 561

- p. 562

- pp. 501–502

- p. 566

- p. 569

- p. 284

- p. 570

- p. 575

- p. 51

- p. 71

- pp. 71–72

- p. 72

- p. 73

- p. 74

- pp. 76–77

- p. 78

- p. 79

- p. 599

- pp. 95–96

- p. 27

- pp. 28–40

- p. 39

- pp. 31, 34

- p. 35

- p. 37

- p. 38

- pp. 62–64

- p. 65

- p. 67

- p. 85

- p. 134

- pp. 134–135

- p. 140

- p. 141

- p. 142

- p. 134

- p. 143

- p. 208

- p. 16

- p. 423

- pp. 15–16

- p. 316

- p. 122

- p. 297

- p. 87

- p. 88

- p. 537

- p. 200

- p. 294

- p. xxi

- p. 365

- p. 192

- p. 165

- p. 240

- pp. 240–241

- p. xix

- p. 335

- p. 75

- p. vii

- p. 355

- pp. 4–5

- p. 7

- p. 245

- pp. 199–200

- p. 351

- p. 240

- p. 244

- pp. 183, 200

- p. 139

Bibliography

This article may contain text from Wikipedia, released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.