The Society for Psychical Research (SPR) is a registered charity founded in 1882, the aim of which is to examine claims of psychic and paranormal phenomena scientifically, without itself holding any view about the existence or interpretation of such occurrences. Run by a council of elected members, its past presidents have included the Conservative prime minister Arthur Balfour (1893) the psychologist William James (1894–1895), and the physicist Lord Rayleigh (1919).

Since 1884 the SPR has published the quarterly Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, containing peer-reviewed submissions in the fields of psychic and paranormal effects, along with theoretical and historical papers. It also publishes less formal articles in its quarterly Paranormal Review.

The society’s early work was chiefly concerned with investigating and exposing fradulent mediums, of whom there were many during the late 19th century. In more recent times its efforts have shifted towards establishing itself as an educational body in the field of what has become known as psi, the collective term for telepathic and other psychical phenomena.

Origins

The Society for Psychical Research (SPR) grew from a discussion between the journalist Edmund Rogers and the physicist William F. Barrett towards the end of 1881. The society’s foundation was proposed at a subsequent conference held on 5 and 6 January 1882 at the headquarters of the Central Association of Spiritualists, previously known as the British National Association of Spiritualists,[1] and the philosopher Henry Sidgwick was appointed as its first president.[2] The SPR thus became the first organisation of its kind in the world, its stated purpose being “to approach these varied problems without prejudice or prepossession of any kind, and in the same spirit of exact and unimpassioned enquiry which has enabled science to solve so many problems, once not less obscure nor less hotly debated.”[3]

Early investigations

Much of the society’s early work involved exposing fake phenomena and fraudulent mediums.[4] In 1886 and 1887 a series of publications by S. J. Davey, Richard Hodgson and Eleanor SidgwickPhysics researcher, activist for the higher education of women, Principal of Newnham College of the University of Cambridge, and a leading figure in the Society for Psychical Research. in the SPR journal exposed the slate writing tricks of the medium William Eglinton. Hodgson and Davey had staged fake séances to educate the public, in which Davey gave sittings under an assumed name. He duplicated the phenomena produced by Eglinton, and then proceeded to demonstrate to the sitters the manner in which they had been deceived. As a result of these exposures, some SpiritualistSystem of beliefs and practices intended to establish communication with the spirits of the dead. members, including Stainton Moses, resigned from the SPR.[5] Moses, himself a medium and one of the society’s first vice-presidents,[6] was subsequently found to have used deception in his own sittings, caught twice in possession of a bottle of phosphorous.[7]

From the 1850s onwards various likenesses of dead people began to appear in photographs, unseen when the exposure was made but visible as translucent images on the developed print.[8] In 1891 Eleanor Sidgwick published a critical paper in the society’s Journal casting doubt on the subject, and discussing the fraudulent methods used by the early photographers, including Édouard Isidore Buguet, Frederic Hudson and William H. Mumler.[9]

The most successful and best-known spirit photographerTechnique popular in the 19th century to capture the invisible spirits of the deceased. in the UK was William Hope, of the Crewe Circle of Spiritualists. The SPR’s conclusion that Hope’s photographs were also fake prompted the author and committed Spiritualist Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to publish a rebuttal in 1922, The Case for Spirit Photography, [10] and ultimately to lead a mass resignation of eighty-four Spiritualists from the society in protest at what they perceived to be its unduly sceptical attitude towards Spiritualism.[11]

Relationship with Spiritualism

Many of the society’s initial members also belonged to the Central Association of Spiritualists, in the rooms of which organisation the SPR was founded.[12] The fundamental tenet of Spritualism was that individual minds survive the death of their bodies, progressing to a higher plane of existence and continuing to evolve onto higher and higher planes thereafter.[13] Psychical phenomena were not merely proof of life after death, but showed that the living could communicate with those discarnate humans, who could reveal to us what they had learned about the afterlife in their own post-death evolution,[14] and in the form of spirit guides could offer “religious comfort and guidance”. [14]

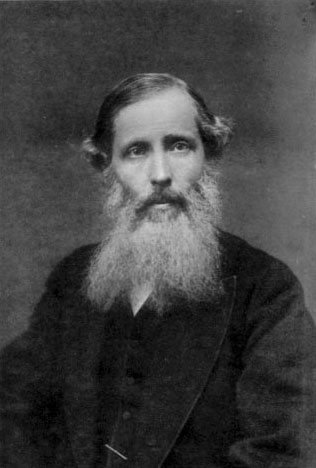

Spiritualists comprised the majority of the SPR’s original committee, but the relationship between the Spiritualist movement and the SPR began to sour after the society’s leadership passed into the hands of a “Cambridge elite” led by Henry Sidgwick, prominent among whom was Frederic MyersEnglish poet, classics scholar, and founder member of the Society for Psychical Research.. Myers and his colleagues believed that the investigation of psychical phenomena should rest on the fundamental primacy of existing physical laws, so should therefore be done under strictly controlled conditions. In contrast, Spiritualists saw the key criteria for a successful manifestation as “one of sympathetic respect”.[15] To a committed Spiritualist, that a particular phenomenon could be faked or had been shown to be fraudulent was not evidence that in every case it had been faked, no matter how many frauds the SPR exposed. For instance, in response to the conviction of probably the most accomplished of the Victorian spirit photographers, Buguet, in a French court in 1875 after he had confessed to his trickery, Conan-Doyle merely observed that “the case for spirit photography would be stronger without him”.[16]

According to the historian of science William Hodson Brock, “by the 1900s most avowed spiritualists had left the SPR and gone back to the BNAS (the London Spiritualist AllianceEducational charity founded in 1884, offering training in mediumship and various divinatory tools. since 1884), having become upset by the sceptical tone of most of the SPR’s investigations.”[17]

Present day

Since the mid-20th century the SPR’s focus has shifted from investigative research towards establishing itself as an educational body. To that end, it has established a specialist library and archive at its London offices and at the Cambridge University Library. Much of the material now published in its Journal explores the relationship between psychical research and related fields such as psychology, philosophy, physics, medicine and social sciences. Although the organisation itself claims to have no opinion on what has become known as psi – the collective term for telepathic and other psychical phenomena – it would be fair to say that the consensus of its members is that psi is real, “and that while the phenomena should certainly be explained in scientific terms, such a science does not at present exist”.[18]

Some sceptics, notably the anthropologist Eric Dingwall, who served as a research officer for the SPR from 1922 until 1927, have been critical of the potential impact of such a consensus view among the society’s members on the objectivity of its investigations. In an essay published in 1971 explaining the reasons for his resignation from the society and his abandonment of psychical research he wrote:

— Eric Dingwall