Wikipedia

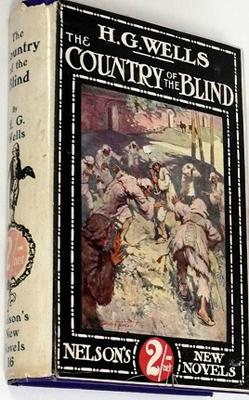

“The Country of the Blind” is the best known of the almost one hundred short stories written by the English author H. G. Wells (1866–1946).[1] It was first published in the April 1904 issue of The Strand MagazineMonthly publication founded by George Newnes, published 1891–1950, credited with introducing the short story to a British audience., and subsequently in book form in The Country of the Blind and Other StoriesCollection of 33 short stories by H. G. Wells, first published in 1911. (1911). Wells later revised the story, and an expanded version with a different ending appeared in 1939.

Told as a third-person narrative, the story centres on the accidental discovery of a latter-day utopia by a mountaineer climbing a fictitious mountain in Ecuador, all the inhabitants of which are blind, and his discomfiture at discovering that far from being considered an asset, his sense of sight is regarded as an affliction.

Synopsis

While leading a group of English mountaineers attempting to climb the unconquered crest of Parascotopetl (a fictitious mountain in Ecuador), Nunez slips and falls. At the end of his descent, down a snowy slope in the mountain’s shadow, he finds a valley, cut off from the rest of the world on all sides by steep precipices. Quite by accident, Nunez has discovered the fabled Country of the Blind, which had been a haven for settlers fleeing the tyranny of Spanish rulers until an earthquake cut the valley off from the outside world. The isolated community prospered over the years, despite a disease that struck them early on, rendering all newborns blind. As the blindness slowly spread over fifteen generations, the people’s remaining senses sharpened, and by the time the last sighted villager died, the community had fully adapted to life without sight.

Nunez descends into the valley and finds an unusual village with windowless houses and a network of paths, all bordered by kerbs. Upon discovering that everyone is blind, Nunez begins reciting to himself the proverb, “In the Country of the Blind, the One-Eyed Man is King”.[a]The earliest version of the proverb appears in Collectanea adagiorum veterum, first published by Desiderius Erasmus in 1500. Erasmus first quotes a Latin proverb: “Inter caecos regnat strabus” – Among the blind the squinter rules. He follows this with a Greek proverb that is similar, but then translates the Greek into Latin: “In regione caecorum rex est luscus” – In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. He believes that he can teach and rule them, but the villagers have no concept of sight, and do not understand his attempts to explain this fifth sense to them. Frustrated, Nunez becomes angry, but the villagers calm him, and he reluctantly submits to their way of life, as returning to the outside world seems impossible.

Nunez is assigned to work for a villager named Yacob. He becomes attracted to Yacob’s youngest daughter, Medina-saroté, and the pair soon fall in love. After winning her confidence, Nunez tries to explain sight to Medina-saroté, but she dismisses it as his imagination. When Nunez asks for her hand in marriage, he is turned down by the village elders on account of his “unstable” obsession with “sight”. The village doctor suggests that Nunez’s eyes be removed, claiming that they are diseased and are “greatly distended”, and because of this “his brain is in a state of constant irritation and distraction”. Nunez reluctantly consents to the procedure because of his love for Medina-saroté. But at sunrise on the day of the operation, while all the villagers are asleep, he sets off for the mountains without provisions or equipment, hoping to make his way back to the outside world.

In the original version of the story, Nunez climbs high into the surrounding mountains until night falls, and he rests, weak with cuts and bruises, but happy that he has escaped the valley. His fate is not revealed. In the revised and expanded 1939 version, Nunez sees from a distance that there is about to be a rock slide. He attempts to warn the villagers, but again they scoff at his “imagined” sight. He flees the valley during the slide, taking Medina-saroté with him.

Commentary

Wells described “The Country of the Blind” as an “exploration fantasy, and one of his best”, but it is also a utopian story, which clearly owes a debt to Plato’s account of Atlantis.[b]Wells said that reading Plato early in life was “like the hand of a strong brother taking hold of me and raising me up”, leading him to fantastic places and novel ideas.[1] The literary critic and President of the H. G. Wells Society, J. R. Hammond, has described Wells as “the last of the great utopists”, and the land Nunez discovers can be seen as a latter-day Atlantis.[1]

Jodie R. Gaudet of Georgetown University has suggested that Wells may not be intending to describe a valley that tangibly exists, but rather a hallucination brought on by Nunez’s concussion caused by his fall. The idea that the entire story takes place in the imagination of the main character is given some weight by Wells’s style of writing; the many ellipses inserted throughout the text – “the passing of time coterminous with an absence of recognition” – may be suggesting that Nunez is drifting in and out of consciousness as he dreams of the country of the blind.[2]

Alternative ending

In the preface to the 1939 edition Wells explains why he decided to rewrite the ending to this story:[3]

In what A. Langley Searles writing in The Wellsian has called a “tack-on love interest”, Nunez and Medina-saroté marry and have four children together, all of whom can see. Though happy in her new life, she looks back nostalgically to her time in the valley, and steadfastly refuses to be treated for her blindness. She reveals why in a conversation with the narrator’s wife:[4]

“But after all that has happened! Don’t you want to see Nunez; see what he is like?”

“But I know what he is like, and seeing him might put us apart. He would not be so near to me. The loveliness of your world is a complicated and fearful loveliness, and mine is simple and near. I had rather Nunez saw for me – because he knows nothing of fear.”

“But the beauty!” cried my wife.

“It may be beautiful,” said Medina-saroté, “but it must be very terrible to see.”

See also

- H. G. Wells bibliographyList of publications written by H. G. Wells during the more than fifty years of his literary career.

Notes

| a | The earliest version of the proverb appears in Collectanea adagiorum veterum, first published by Desiderius Erasmus in 1500. Erasmus first quotes a Latin proverb: “Inter caecos regnat strabus” – Among the blind the squinter rules. He follows this with a Greek proverb that is similar, but then translates the Greek into Latin: “In regione caecorum rex est luscus” – In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. |

|---|---|

| b | Wells said that reading Plato early in life was “like the hand of a strong brother taking hold of me and raising me up”, leading him to fantastic places and novel ideas.[1] |

References

Bibliography

External links

- Full text of “The Country of the Blind” at Project Gutenberg